By Anastassiya Reshetnyak

Anastassiya Reshetnyak was a Spring 2021 CAAFP Fellow. She graduated from al-Farabi Kaz NU (BA and MA in Regional Studies) and is currently involved in the PhD program in International Relations at the Gumilev Eurasian National University, Kazakhstan. Her research interests include prevention of violent extremism (PVE),societal security, international security and youth policy in Central Asia. As a member of the Paper Lab Research Center, she conducts research in the field of public policy in Kazakhstan and Central Asia and participates in the promotion of an evidence-based approach to political decision- making. She contributes to a number of PVE-related projects of UNDP, UNODC, IOM, and USAID. Previously, Anastassiya worked at Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies under the President of RK as a Senior Research Fellow.

Anastassiya Reshetnyak was a Spring 2021 CAAFP Fellow. She graduated from al-Farabi Kaz NU (BA and MA in Regional Studies) and is currently involved in the PhD program in International Relations at the Gumilev Eurasian National University, Kazakhstan. Her research interests include prevention of violent extremism (PVE),societal security, international security and youth policy in Central Asia. As a member of the Paper Lab Research Center, she conducts research in the field of public policy in Kazakhstan and Central Asia and participates in the promotion of an evidence-based approach to political decision- making. She contributes to a number of PVE-related projects of UNDP, UNODC, IOM, and USAID. Previously, Anastassiya worked at Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies under the President of RK as a Senior Research Fellow.

In 2016, the press service of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Kazakhstan disseminated information on the “social portrait of a terrorist.” According to this, the typical terrorist in Kazakhstan is “an unemployed young man with a secondary education, without a special religious education; he is married and has several children.”[1] Without discussing the relevance of such generalization, it is necessary to say that, when it comes to violence, particular attention is always paid to young people.

Young people are indeed one of the groups most vulnerable to violent extremism. Youth are claimed to be more unstable in terms of their values and attitudes, to have a special sensitivity to injustice, and to romanticize dangerous paths to success. Dawson identifies three key factors explaining why young people are more vulnerable to radicalization than adults: first, in their quest for significance, they often face real or perceived humiliations; second, they pay great attention to moral concerns and feel personal moral duties; and third, they are more oriented toward action, adventure, and risk.[2] When it comes to violent jihadist movements, Roy attributes their popularity among European Muslim youth to so-called generational revolt: second- and third-generation Muslim migrants (mostly from the MENA region) consider themselves ready to fight for religious values and aim to become “more Muslim than their parents.”[3]

In Kazakhstan, a similar gap is visible in relations between Soviet-born parents with atheist backgrounds and their children born in the post-Soviet period, who have enjoyed a higher level of religious freedom. This dynamic has created a generation of neophytes—people who cannot relate to the family religious tradition and feel forced to seek their own modes of belief.

Kazakhstan, where several terrorist attacks took place in 2011-2012 and 2016, has developed a policy for preventing youth violent extremism that pays particular attention to promoting such narratives as tolerance, national values, the Kazakhstani form of Islam, secularism, etc. However, the fact that more than 400 Kazakhstani fighters traveled to Syria and Iraq to join ISIS in 2013-2015[4] shows that the current policy has had questionable effects.

This paper explores the effectiveness of the Kazakhstani approach to preventing youth from becoming radicalized to violent extremism and terrorism. To do so, it examines and tests the narratives that the government claims are effective against the ideology of violent extremist groups, as well as looking at the approaches of other states and organizations toward young Kazakhstanis. In the final section of the paper, several recommendations for improving youth PVE policy in Kazakhstan are given.

Theoretical Framework

The Problem of National PVE Programming

In 2016, the UN Secretary-General presented a Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism to encourage the international community to develop context-based national plans for preventing and countering violent extremism. However, there is still no globally shared understanding of the terms “extremism” and “violent extremism.”

This situation raises a number of theoretical and methodological issues. While setting forth the general contours of the international PVE agenda, supranational actors leave the problem of defining the threat itself—as well as its ideological basis and instruments for addressing it—to national governments. Thus, the fight against violent extremism may take different forms depending on a particular state’s legislation, power relations, local context, etc.

According to USAID, violent extremism (VE) is “advocating, engaging in, preparing, or otherwise supporting ideologically motivated or justified violence to further social, economic or political objectives.”[5] The Center for the Prevention of Radicalization Leading to Violence describes radicalization to VE as a process of shaping an individual system of beliefs based on personal, collective, social, and psychological factors that justifies violence as a legitimate means of goal attainment.[6]

How can radicalization to VE be prevented and how should the government address this issue in terms of programming (aims, target groups, and intervention instruments)? On the societal level, according to Holmer and Bauman, there are two main approaches: studying the factors that affect violent extremism (developmental approach); and studying the actors who provoke or work to prevent VE, as well as relations between them (conflict analysis).[7]

In the developmental approach, push and pull factors, as well as contextual factors, are taken into account. The push factors “are important in creating the conditions that favor the rise or spread in appeal of violent extremism or insurgency,” while the pull factors make this choice attractive and “are associated with the personal rewards which membership in a group or movement, and participation in its activities, may confer.”[8]

Table 1. Factors of radicalization

| Contextual factors | Pull factors | Push factors |

| Fragile state with ineffective security services | The existence of well-organized violent extremist groups with compelling discourses and effective programs that are providing services | Socio-economic: marginalization, discrimination, inequality, persecution or the perception thereof, limited access to quality and relevant education |

| Bad governance; the lack of rule of law | The existence of radical institutions | Political: denial of rights and civil liberties, local conflicts |

| Support of violent extremist groups by the government | Social networks and group dynamics | Cultural: the usage of religion for violent extremist purposes, threats of culture, traditions, values |

| Proactive religious agenda | Poor service delivery (including incompetence and limited funds) | |

| Corruption and criminality | The spread of illegal economic actions |

Source: Guilain Denoeux and Lynn Carter, “Guide to the Drivers of Violent Extremism,” USAID, 2009, accessed September 29, 2021, https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadt978.pdf.

The conflict analysis approach to extremism was developed in the United States in 2008-09. Structurally, it looks like a standard assessment of the conflict, with three major questions asked: (1) which actors may accomplish violent actions; (2) which groups are their targets; and (3) which actors play enabling, protecting or peacebuilding roles.[9] Such an approach implies an assessment of motives, perceptions, narratives, and relationships between interest groups regarding the problem of violent extremism. In practice, use of this tool can help understand what conditions contribute to an individual or collective predisposition toward violent extremism and how these conditions can be affected.

National PVE policy is therefore a slate of measures addressing the key factors causing radicalization (such as marginalization, socio-economic deprivation, feeling of injustice, lack of opportunities, etc.) through education, engagement, and counter- or alternative narratives.

PVE policy is grounded in national legislation. The 2005 law “On countering extremism” defines extremism as “organization and/or commission by individual and/or legal entity, consolidation of actions of individuals and/or legal entities on behalf of organizations recognized as extremist in the established procedure; individual and/or legal entity, consolidation of actions of individuals and/or legal entities pursuing the following extremist purposes.”[10] The law distinguishes 3 types of extremism: political, national, and religious.

The Kazakhstani legislation on extremism, including the Criminal Code, does not contain clear definitions of religious extremism. This, according to the report of the UN HRC, “provides unlimited possibilities for applying punitive measures against individuals or groups of persons who may seem suspicious to some government agencies, including law enforcement.”[11] At the same time, it also produces a situation in which measures for preventing violent extremism may be understood very broadly.

Why Are Youth Important?

It is widely accepted that youth are the main target of any group that advocates violent methods for achieving political and other goals.[12] Youth may be vulnerable to violent propaganda due to lack of experience, disordered life, conflicts with relatives, lack of strong connections, lack of life prospects, etc.[13]

For instance, research conducted in the Indo-Pacific region shows that the main factors of youth vulnerability to violent extremist propaganda were the following:[14]

- In Bangladesh: large proportion of youth in the population in combination with high youth unemployment and political fluctuations.

- In Indonesia: corruption, inequality and disenchantment with democracy, “inherited jihadism” and radicalization in Islamic study circles.

- In the Philippines: marginalization of Islamic groups by the government; disillusionment with peace processes, financial incentives.

Youth resilience to violent radicalization can be accomplished by ensuring the following conditions within a society:

Table 2. Factors underpinning youth resilience to violent extremism

| Cultural identity and connectedness | Familiarity with one’s own cultural heritage, practices, beliefs, traditions, values, and norms (can involve more than one culture); knowledge of “mainstream” cultural practices, beliefs, traditions, values, and norms if different from own cultural heritage; having a sense of cultural pride; feeling anchored in one’s own cultural beliefs and practices; feeling that one’s culture is accepted by the wider community; feeling able to share one’s culture with others |

| Bridging capital | Trust and confidence in people from other groups; support for and from people from other groups; strength of ties to people outside one’s group; having the skills, knowledge, and confidence to connect with other groups; valuing inter-group harmony; active engagement with people from other groups |

| Linking capital | Trust and confidence in government and authority figures; trust in community organizations; having the skills, knowledge, and resources to make use of institutions and organizations outside one’s local community; ability to contribute to or influence policy and decision-making relating to one’s own community |

| Violence-related behaviors | Willingness to speak out publicly against violence; willingness to challenge the use of violence by others; acceptance of violence as a legitimate means of resolving conflicts |

| Violence-related beliefs | Degree to which violence is seen to confer status and respect; degree to which violence is normalized or tolerated for any age group in the community |

Source: M. Grossman, “Understanding Youth Resilience to Violent Extremism: A Standardised Research Measure: Final Research Report,” Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, Deakin University, 2017, p. 8.

International organizations as well as national governments consider youth as “agents of change” able to turn the tide on VE. Thus, empowering youth is one of seven main recommendations made by the UN PVE Agenda for Action.[15] According to this document, young people should be:

- Supported as participants in PVE activities at all levels

- Included in decision-making processes

- Engaged in an intergenerational dialogue

- Equitably represented in PVE

- Involved in mentoring programs

- Empowered and encouraged to engage in social entrepreneurship to address the specific needs of youth

Youth in Kazakhstan’s PVE Policy

In line with the global trend, people aged 14-29 (as the Kazakhstani legislation defines youth) are a special focus of the government when it comes to preventing and countering violent extremism. The following data confirm that this approach is appropriate:

- Young people represent 20.2% of the Kazakhstani population, or 3.76 million people.

- According to official statistics, youth unemployment is 3.6% (2020), while the overall level is 4.6%.[16] At the same time, among working young people 446,300 are self-employed. The share of young people in the NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training) category in Kazakhstan was 7.6% as of the end of 2020.[17]

- Young people aged 14-28 committed 11.2% of crimes in the republic in 2020 (98.9% of criminals were not in work or education); in Mangystau oblast, the rate is 22.3%. According to the estimates of the “Youth” scientific research center, more than 55% of extremist offenders are young people aged 17-29.[18]

- According to a survey conducted by KIPD “Rukhani Zhangyru” in 2020, 79.9% of respondents do not participate in the activities/events of youth organizations.[19] Youth is also largely outside the political institutions: the average age of Senate deputies is 56.5,[20] of Majilis deputies 49.7,[21] and of regional akims 55.[22]

This combination of factors is a fertile breeding ground for the spread of violent extremism. According to the Counterterrorism Center of the Republic of Kazakhstan, in 2019 a total of 140 people were convicted of crimes related to terrorism and religious extremism,[23] a figure that fell to 32 in the first half of 2020.[24] As noted by Anna Gussarova, recent data on the specifics of offences related to terrorism and violent extremism have not been publicly available since 2017.[25] However, anecdotal evidence and press release data of the National Security Committee permit the conclusion that, as in the 2010s, the vast majority of such offenses are connected to incitement of hatred (Article 174 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan) and propaganda of terrorism or public calls for an act of terrorism (Article 256 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan). These developments show that the problem of violent extremist offenses (as it is understood in the Kazakhstani context) is currently restricted to combatting the opposing narratives.

Development of PVE Policy

Kazakhstan began to develop its PVE program in 2013 in response to violent acts considered as terrorist attacks in Atyrau, Taraz, and Almaty in 2011. As of 2021, it is in the final stage of the second PVE program cycle. The goal of the first State Program on Countering Religious Extremism and Terrorism (2013-2017) in terms of PVE was the “improvement of measures for the prevention of religious extremism and terrorism, aimed at the formation in society of a tolerant religious consciousness and immunity to radical ideology.”

The second Program, for 2018-2022, sought “improvement of measures for the prevention of religious extremism and terrorism, aimed at the formation in society of immunity to radical ideology and zero tolerance to radical manifestations.”The aforementioned statements are repeated in the Concept of the State Youth Policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan until 2020 “Kazakhstan—2020: A Way to the Future” (2013).

The broad interpretation of religious extremism affects the strategy for countering and preventing this threat. As the objectives of both PVE programs are vague, they fail to meet the criteria of the theory of change, which requires the indicators of programming to be clear, useful, measurable, reliable, and valid.[26] Instead, the stakeholders involved at different stages of the programs’ implementation approach the issue from different perspectives.

Over the past seven years, youth has been addressed in PVE programs in the following ways:

Table 3. The role of young people in PVE in Kazakhstan

| State program 2013-2017 | State program 2018-2022 | Non-governmental activities | |

| Youth as at-risk group (object) | Lectures by information-propaganda groups to reach 100% “mastering the necessary amount of knowledge about religion for a conscious attitude to the surrounding reality and critical perception of the received information of a radical religious nature.” Leisure infrastructure (sports, culture, etc.) to create “conditions for proper cultural, spiritual, moral, patriotic, physical development and upbringing of children and youth.” Propaganda on social media to “form a persistent rejection of destructive ideology among young people,” “a consciousness in the youth environment that corresponds to the traditions and cultural heritage of the people of Kazakhstan,” and “educat[e] young people in the spirit of Kazakhstani patriotism, based on fundamental moral, ethical and cultural values.” | Lectures by information-propaganda groups. Address work with representatives of “religious groups and communities.” Propaganda on social media, including “using visualization methods of outreach and counter-propaganda materials for young people (videos, video game elements, and interactive techniques).” “Improve measures to reorient young people to study in domestic theological or secular educational institutions.” | In the framework of state social order; Projects of UN institutions, OSCE, EU, and USAID aimed at addressing the pull and push factors of radicalization to violent extremism, such as unemployment, marginalization, and lack of education and opportunities. |

| Youth as an agent of change (subject) | “In order to strengthen interfaith harmony and the stability of the socio-political situation in the country, it is necessary to more actively involve the population and civil society institutions in the sphere of countering extremism and terrorism.” | “Conducting advocacy through the Internet and social networks aimed at creating immunity to radical ideology, zero tolerance for radical manifestations in the field of religious relations, and de-radicalization, including by […] attracting non-governmental organizations through the state social order, as well as religious associations.” | Since 2015: “KazakhStan for Peace”—NGO promoting narratives of tolerance. Projects of UN institutions, OSCE, EU, and USAID aimed at improving the engagement of at-risk youth in PVE activities: volunteering, social entrepreneurship, education, etc. Sporadic activities of volunteers, mostly in social networks. |

Source: Author’s compilation based on Kazakhstani PVE programs.

To sum up, governmental PVE efforts targeted at youth can be divided into three groups:

- Promotion of religious literacy. The lack of religious education remains the authorities’ main argument in their PVE activities. However, there is evidence from around the world that this approach is not efficient and may even cause new waves of radicalization by raising the question of identity for some parts of a multicultural society.[27] The government’s monopoly on the “proper version” of religion undermines the idea of religious pluralism. In the case of Kazakhstan, the low level of support for representatives of the SAMK (Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Kazakhstan), especially among youth, may become a push factor for radicalization.[28]

- Patriotic education (culture and traditions of Kazakh people; “Kazakhstani values” such as tolerance, interfaith peace, and harmony). As a group, youth are usually not interested in such officially promoted values. Moreover, the representatives of executive power understand this, claiming that “young people misunderstand the meaning of the word “patriotism”[29] and hence recognizing the activities of promoting “patriotic conscience” as a policy failure. Since the crisis of the mid-2010s, the agenda of official propaganda has become increasingly distant from the social and economic reality.[30] Young people—who face unemployment, corruption, nepotism, and a lack of justice and are much more sensitive to these trends than other generations—do not accept the promotion of patriotism and tolerance as intrinsic values. Over the last two years, youth have called for changes to the status quo,[31] and these developments require the authorities to change the narratives addressed at this group.

- Development of leisure facilities, mostly in rural areas and small towns (only in 2013-2017). This measure has proven to be ineffective in the framework of PVE if implemented separately from the creation of new jobs and ensuring young people’s access to social goods.[32]

Methodology

In order to trace the development of PVE policy targeting young people in Kazakhstan, I conducted content analysis of legislation and PVE programs. Young people’s perceptions of the PVE information policy were analyzed through an online survey and asynchronous online focus groups. Structure and level analysis, as well as SWOT-analysis, were used to develop recommendations for policymakers and stakeholders.

An online survey about youth perspectives on violent extremism and PVE policy in Kazakhstan was conducted in April 2021. 631 people took the survey (515 women and 116 men); 217 responded in Kazakh and 414 in Russian. They were asked about their experience of consuming PVE content offline and online. Based on demographic characteristics and their answers, 20 respondents were invited to participate in 2 asynchronous focus group discussions, one each in Kazakh and Russian.

Several interviews were conducted with government affiliates and independent practitioners to determine the paths of PVE policy development, its features, and vectors of further development.

Frames of Youth-Oriented PVE

PVE activities in the framework of the State Program are commonly carried out at national (Ministry of Information and Social Development) and regional (Departments for Religious Affairs in akimats) level. The following activities might be classified as “soft” PVE measures in the framework of the state policy:

Table 4. Instruments of PVE in Kazakhstani governmental policy

| Offline | Online |

| Advocacy groups | Government agencies’ sites and accounts on social networks |

| Consultations in the regional Departments of Religious Affairs | Government order for counter-propaganda on the Internet |

| “114” hotline | Media monitoring |

| Conferences and roundtables | Collaboration with bloggers and opinion leaders |

| Government order for counter-propaganda in the media | |

| Publication of literature in the framework of increasing religious literacy | |

| Development of booklets and billboards |

Source: Author’s compilation based on Kazakhstani PVE programs.

Reasons for youth radicalization to violent extremism.

According to the official narrative, young people radicalize due to “religious illiteracy[33] that is being used by foreign violent extremist recruiters controlled by geopolitical rivals of Kazakhstan.”[34] These ideas are expressed in various forms by PVE practitioners at all levels. During expert interviews, the following factors were listed:

- Search for identity peculiar to youth

- Psychological barrier between young people and their parents

- Religious leaders who studied Islam abroad (e.g., in Egypt or Saudi Arabia) and now promote a “wrong” perception of religious norms among believers

- The Internet (and social media in particular) as a source of violent extremist propaganda

- Socio-economic and political factors

- Religious ignorance

- Youthful exuberance and looking for a thrill.

It is remarkable that practitioners focus primarily on pull and to a lesser degree on push (religious literacy) factors, leaving contextual factors entirely outside the scope of the discussion. This has resulted in PVE measures oriented toward changing young people’s minds without corresponding structural changes to governmental social and security policy.

Instruments of PVE policy targeting youth.

The interviewed experts agreed that youth are particularly vulnerable to radicalization. They also expressed uniformity in terms of their views of which instruments are most effective for PVE activities among youth. Top of the list, they say, are information and explanatory groups (IEGs) consisting of theologians, psychologists, civil society representatives, religious organizations, police and domestic authorities, and local community leaders:

The main part of the IEGs should work with those young people who are not religiously practicing people but consider themselves to be believers. Or, if they are practitioners, then they are not very well versed in the traditional direction; they cannot distinguish the traditional direction from the destructive denomination (representative of a regional Department for Religious Affairs (DRA)). The second most popular instrument is promotion of PVE narratives on social media: Accounts are maintained on various social networks, counter-propaganda content is posted: videos, presentations that discredit the ideology of terrorists and extremists, describe their features and consequences of their activities or ways of involvement. On the other hand, there is also positive content, such as tolerance, equality of religions, the importance of human life, quotes from great and wise ancestors, not only of our homeland, but also foreign ones. That is, the promotion of the idea of humanism, including traditional national values, since the titular nation is the majority and the emphasis of propaganda is on this group (a former representative of a regional DRA).

Experts note that the quality and popularity of these instruments grew during the pandemic, when the majority of offline measures were unavailable. Whereas in 2016 the social media content of DRA accounts consisted of borrowed information and media and included dry information about offline DRA activities,[35] DRA employees now participate in courses on social media marketing, targeting, and copywriting that help them to create and promote more attractive messages on social media.[36]

Such instruments as partnership with NGOs and youth involvement in PVE activities (volunteering, competitions, etc.) are less popular among practitioners. For instance, two of them remarked that the activities of NGOs are not effective due to the nature of the state social order, which chooses the cheapest services on offer rather than allowing the most experienced NGOs to participate in social projects.

In the framework of the state social order or otherwise, governmental institutions attempt to generate interest in the topic of extremism and terrorism prevention among young people. For instance, in November 2020, the Office of the Prosecutor of Nur-Sultan announced a contest among youth in the capital city to “bring the attention of the population to the problem of religious extremism and terrorism,” with three categories: “Best work of a Vine blogger” (best short video), “Best collage/demotivator,” and “Best project [aimed at] enhancing social activity of the Kazakhstani population.” The prize fund for the contest exceeded 2.6 million tenge.[37] A month later, the akimat of Nur-Sultan posted an article about the contest that indicated that the winners had been determined by a jury and received their prizes. Overall, more than 140 applications were submitted.[38] However, these materials were never posted on social media—neither those belonging to the Office of the Prosecutor of Nur-Sultan nor those belonging to the akimat.

An expert who worked on one of the UN PVE projects noted that from the socio-economic standpoint, Kazakhstan has the instruments necessary to prevent radicalization among youth: employment and business projects for young people. The efficiency of these programs, however, is questionable:

The effectiveness of the use of this money was not mentioned in governmental documents; those contained just information about the implementation. Therefore, of course, intuitively I understand that it was ineffective, but to be objective, I have no evidence that it was effective or ineffective (former UN staff member who worked on a PVE project in Kazakhstan).

Youth Vision of the PVE Agenda

The survey I conducted among youth shows the discrepancy between officially stated goals and their reception by young people.

Among those who had personally seen content propagating violent extremism (an average of 16% of respondents: 14.2% among those who submitted their responses in Kazakh and 16.9% among those who submitted their responses in Russian), more than half (58.4%) described themselves as religious persons who complied with the strictures of their faith. Most of them wrote that these materials were “uninteresting” or “scary,” although some described them as “something new,” “made in a very interesting format,” and with “bright attractive pictures, wise quotes, admonitions.”

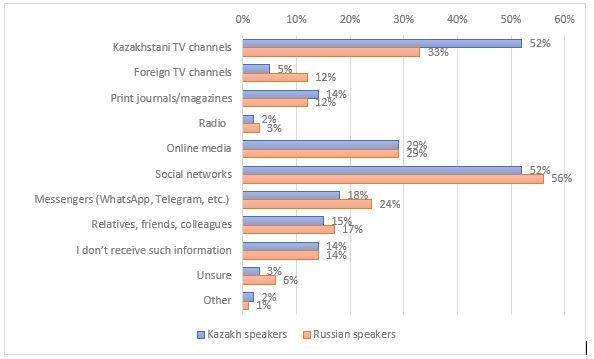

As is clear from Figure 1, young people mostly access information about combating extremism and terrorism via social networks, national television, and online media. Interestingly, more than half of Kazakh-speakers receive such data from TV channels, while this is a source of information for only one-third of those who filled out the survey in Russian.

Figure 1. Distribution of answers to the question “From what sources do you most often get information about combating extremism and terrorism?” (multiple choice)

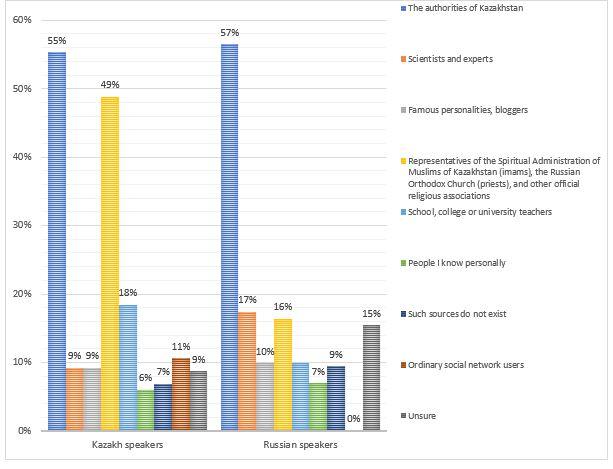

The next questions on PVE sources were about confidence. There were significant differences depending on the language respondents use. Thus, while both groups trust the government equally, Kazakh-speakers were almost three times as likely as Russian-speakers to say that they considered religious leaders the most reliable source of information on PVE, while Russian-speakers were twice as likely as Kazakh-speakers to place their trust in scientists and experts.

Figure 2. Distribution of answers to the question “Which sources, in your opinion, distribute the most reliable information on the prevention of terrorism and extremism?” (multiple choice)

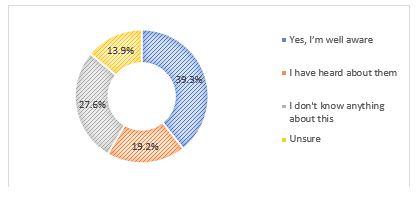

The main objective of the survey was to determine young people’s level of awareness of Kazakhstani PVE policy. The majority of respondents (58.5%) were well aware of or had at least heard about governmental PVE activities.

Figure 3. Distribution of answers to the question “Do you know about events that the government conducts to prevent extremism among young people?”

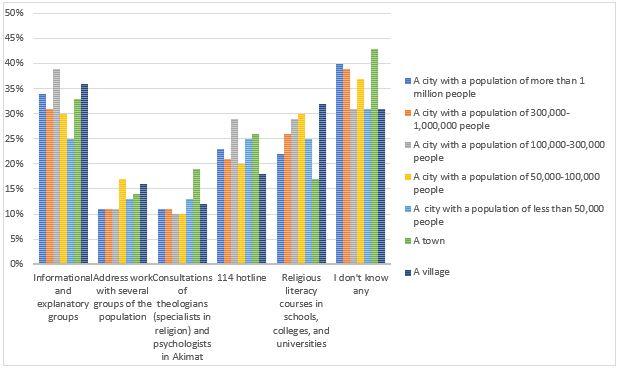

As can be seen in Figure 4, information is distributed relatively equally in big cities and in rural areas; on average, 30-40% of respondents do not know any offline instruments of state PVE policy. The most recognizable activities were information and explanatory groups (25-36%) and religious literacy courses in educational institutions (17-31%). Less than 15% know about the consultations with theologians, psychologists, and akimats and the targeted work with vulnerable groups.

Figure 4. Distribution of answers to the question “What kind of state activities on the prevention of religious extremism and terrorism offline are you aware of?”

Answering a separate question about information-explanatory groups (as this is the main offline instrument for awareness-raising), 10% indicated that they had participated in these groups’ events; 17% had seen their materials on the Internet; 31% had heard something about their activities, but had not come across them; and 42% had either not heard anything about their activities or chose “not sure.”

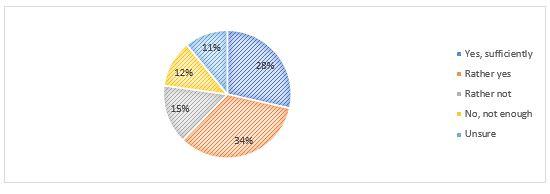

At the same time, asked “Do you think that public authorities in Kazakhstan raise awareness and conduct advocacy for the prevention of religious extremism and terrorism sufficiently?”, 62% answered “yes” or “rather yes.” This may indicate a high level of conformity among the youth audience and their discomfort with criticizing the state authorities.

Figure 5. Distribution of answers to the question “Do you think that public authorities in Kazakhstan raise awareness and conduct advocacy for the prevention of religious extremism and terrorism sufficiently?”

The Perception of PVE Products

In the second stage, 20 participants were encouraged to express their opinions on materials published by several of the most popular DRA accounts on social networks (mostly Instagram and YouTube).

Table 5. Media content created in the framework of governmental PVE activities shown to the participants of asynchronous focus group discussions

| Values | Russian | Kazakh |

| “Non-traditional” or “destructive” ideologies | Video “What is Salafism?” describing Salafi ideologies, differences between it and “traditional” Kazakh Islam; instructions on how to identify a Salafi supporter; dangers of the distribution of Salafi ideology (destroying national identity, etc.) | A series of Instagram stories: 10 indicators of “destructive religious denominations (DRD)”the influence of DRDreasons why people join DRDwhat to do if those close to you show signs of DRD (helpline number, address of support center) |

| Recruitment by violent extremist groups | Video about the choice. How to behave in difficult life situations; it’s critically important to resist VE recruitment: “An incorrectly chosen step practically does not give a chance to return to normal life.” | Video. A chat of father and son on values (son is a sportsman who choses Kazakhstani flag over the flag of ISIS) |

| A Bernard Shaw quote: “We rarely feel the charm of our own tongue until it reaches our ears under a foreign sky,” with a photo of the Zhusan[39] operation in the background | ||

| Patriotism, Tolerance/Multiculturalism, | “Interconfessional harmony is a pledge of peace and glory” A picture of representatives of different confessions with the description of “Kazakhstani model of interethnic and interconfessional consent” | A quote from famous Kazakh writer Dulat Issabekov about fanatism and lucidity |

| Danger of violent extremism | A series of Instagram stories describing the unconstitutional character of religious extremism and the way radical groups behave | A list of films about religious extremism and radicalism |

| Critical thinking | Video “Factchecking and Religion” describing what factchecking is and how to use it to verify information about religion |

Respondents were asked to assess the appearance and content of materials posted on social media and to indicate whether, in their opinion, these materials respond to the narratives of the official PVE policy. Finally, they were invited to answer the question of whether, having seen these materials, they would subscribe to the social media channels that posted these materials.

“Non-traditional” or “destructive” ideologies

The video describing Salafi ideology (in Russian) and the series of pictures about destructive religious denominations (in Kazakh) get average grades of 4.5 and 4.8 out of 5. These materials, according to respondents, inform about the danger of terrorism and extremism (70-80%) and have practical benefits for viewers (80% and 60%, respectively). At the same time, some of them notice that materials might discriminate against a part of Kazakhstani society (20% and 50%):

In many ways, some of his statements are too harsh, one way or another, this narrative may cause fear of this stream of religion that may lead to a negative attitude on the part of society toward

hijab-wearing persons who are not Salafis (female, 20 y.o., Nur-Sultan, atheist; about the video on Salafis).

Recruitment by violent extremist groups

Russian-speakers did not recognize a photo of a Kazakhstani soldier and a baby during the Zhusan operation, with the result that the message of the picture was blurred. While 80% of respondents agreed that the picture inspired feelings of patriotism and ethnic identity, they were confused about its meaning:

I really liked the statement, but it does not connect to the picture, where, apparently, an American soldier helps an injured family (female, 20 y.o., Nur-Sultan).

It’s nice to hear native speech abroad, one remembers the homeland (male, 27 y.o., Pavlodar oblast).

A motivational video in Russian that calls on viewers to choose the right path, even in a difficult situation, was not very popular among respondents (4.4/5). However, 8/10 participants noted that it informs about the danger of violent extremism. 7/10 indicated that it informs about Kazakhstani legislation in the field of terrorism and the prevention of religious extremism (even though there was no such information in the video):

The author wanted to say that there are no easy ways—cheese is free only in a mousetrap (female, 27 y.o., Almaty).

The video in Kazakh was about a father who thinks about joining ISIS and his son who forces him to think about patriotism:

Love of faith, love for one’s country in the heart of a small child, this is the world of love (female, 17 y.o., Almaty).

This video should be watched by all those who want to turn or have turned their life path away from the main religion (female, 21 y.o., Atyrau oblast, housewife).

On the other hand, 40% of respondents noted that the video may infringe upon or violate someone’s interests and rights.

Patriotism, Tolerance, Multiculturalism

The state authorities claim that these values are part of the “national cultural code” of Kazakhs and Kazakhstanis. The ideas of common destiny and peaceful coexistence are translated not only to the Kazakhstani audience but also externally, in foreign policy.

The picture in Russian (see Figure 6) received the most positive feedback among respondents:

It explains that there are a lot of tolerant people in Kazakhstan (female, 21 y.o., Karagandy oblast, civil servant).

I think in spite of religion and in general, a human is primarily a “human” (male, 19 y.o., Almaty, ethnic Korean, Russian Orthodox).

Figure 6. A picture from an Instagram post by the Department for Religious Affairs of Almaty region

Source: https://www.instagram.com/dinisteri_almobl/

Patriotic content in Kazakh often appeals to famous people, politicians, and historical and cultural figures. A picture featuring a portrait of and quotation from Kazakh writer Dulat Issabekov about the incompatibility of fanaticism and critical thinking was selected for the focus group. The only two reactions to this picture were support (70%) and appreciation (50%):

As can be seen from the general picture, fanaticism is currently greatly exaggerated. Our youth imitate other people—that is, they become fanatics. And where there is rationality, there is both development and modernization (female, 19 y.o., Turkestan oblast, student).

I love all these fiery, thoughtful words from Dulat Issabekov (male, 19 y.o., Kyzylorda oblast, student).

The danger of religious extremism

The Instagram stories in Russian describing VE-related terms, state policy, and the threats that VE poses to society garnered the largest number of negative reactions. Only 30% of respondents indicated that the content was in any way useful to the audience, while two respondents claimed that the material caused irritation and two that it inspired fear. Only three respondents noticed that the material contained the contact information of a regional DRA:

Everything is badly written. Why come up with such terrible opinions? We live in an independent republic, so I think this is all wrong (female, 24 y.o., Turkestan oblast, lives in a town).

I’m afraid that terrorists might be hiding under such posts (female, 21 y.o., Karagandy oblast, lives in a city of 50-100,000 people).

For the Kazakh-speaking audience, one of the regional DRAs proposes a selection of films on the topics of radicalization and extremism. While 9/10 respondents claim that this publication may be useful to the audience and 8/10 recognize it as a source of information about the danger of terrorism and violent extremism, the overall grade given to this post is 4.4:

I love it because these films shape the understanding of extremism and radicalism (female, 19 y.0., Almaty, student).

It’s useful to watch films about religion, but young people do not watch such films (male, 16 y.o., Aktobe oblast, student).

Critical thinking

Lastly, materials promoting critical thinking have started to appear on governmental bodies’ social media. The video about fact-checking made a positive impression on focus group participants: the average grade was 4.9 and the practical utility of the information was noted by 10/10 respondents.

It is wrong to use religion to be popular; it is better to look for what you like in religion; it is wrong to oppose religion to what you do not like (male, 16 y.o., Aktobe oblast, student).

In general, and while watching the video, I was able to get full information about fact checking. It is the 21st century of information technology, and each person must develop oneself, avoid bad habits, bad deeds (female, 19 y.o., Turkestan oblast, student).

In general, young people perceive the information in a positive way. However, they identify the following deficiencies:

- In some cases, respondents do not see useful information behind the content’s frightening message

- Narratives are presented in an unattractive way (poor image design or video editing)

- There are discriminatory messages that create a negative image of, for example, Muslim believers

- Some materials are too long, difficult to comprehend, or not interesting enough to read or watch all the way through

Moreover, some respondents (mainly representatives of national and religious minorities, as well as residents of small settlements and cities with a population of a million and more) said that they were not interested in religious topics and that they were not ready to voluntarily consume such content.

Kazakh-speaking respondents were more likely to subscribe to the account on social media that posts the materials they saw (5-7/10 indicated that they would subscribe). Among Russian-speaking respondents, only 3-4/10 expressed a desire to subscribe (with the exception of the picture on multiculturalism, which garnered 8 “potential subscribers”). Several of them said that they are not interested in such information.

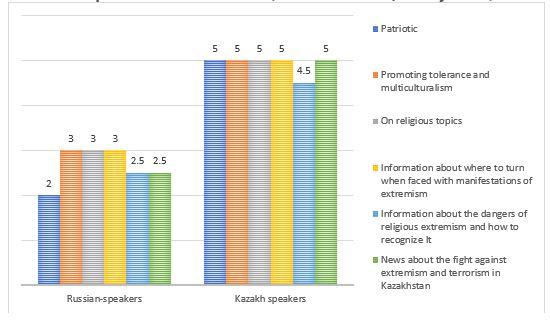

Figure 7. Distribution of answers to the question “What materials do you think are useful for the prevention of extremism?” (1 – not useful at all, 5 – very useful)

As evident from Figure 7, there are significant differences between Kazakh- and Russian-speaking audiences. Whereas Russian-speakers do not see information policy as a potential tool in the fight against violent extremism, Kazakh-speakers believe that all information might be useful for these purposes. Interestingly, patriotic content garners the lowest support, followed by information on how to recognize violent extremism.

In concluding the focus group, the following question was asked: “In your opinion, what can be improved in PVE information policy, given that it is aimed at young people?” The results in the Russian- and Kazakh-language focus groups were not vastly different.

Russian-speaking respondents indicated that most materials are good and advised policy makers to promote these messages more actively on social networks. Among the problems, they noted the low quality of several materials. Some of them also expressed the view that offline activities should be developed:

[It is necessary to] strengthen the interaction of Youth Resource Centers with schools and universities (male, 21 y.o., East Kazakhstan oblast, lives in a town).I think it is worth opening youth centers so that young people of different faiths rally (female, 23 y.o., Karagandy oblast, housewife, ethnic Russian).

Kazakh-speaking participants devoted greater attention to the religious agenda. In the view of several respondents, preaching is a good instrument for preventing religious extremism. They suggest deepening this activity by paying greater attention to religious leaders and narratives:

It is necessary to encourage people not to go down the wrong path, you need to start with the closest people, they will be happy that you have gained confidence and help people not to go down the wrong path (female, 16 y.o., Almaty, student).

In general, it would be better if the media exposed the danger of heresy, spoke out against extremism and terrorism and promoted it [narratives against extremism]. Trainings on various religious topics will shine brighter ((female, 19 y.o., Turkestan oblast, student).

Analysis of youth perceptions of PVE narratives and particular materials being circulated online disclosed the following:

- Young people mostly approve of the ideas expressed in these materials, but these ideas are too broad and “universal” not to be approved (e.g., tolerance, patriotism, etc.)

- At the same time, the messages and objectives of these materials may be unclear to youth or even seem aggressive or discriminatory (especially to religious and ethnic minorities)

- Overall, while the appearance and quality of the messages is growing year by year, there has not been a qualitative increase in relevance to the youth agenda.

Conclusion

While the focus of the government has been on countering violent actions and on handling the fallout of these actions, a more strategic vision has not been elaborated that could offer inclusive and long-term measures to address the problem of radicalization effectively. Instead of encouraging youth leaders to work on building social resilience, state institutions create stillborn youth organizations to propagate the ideas of tolerance and multiculturalism stipulated by state politics. The real aim of such organizations is to execute the budget; to do so, they organize questionable activities which do not have any proven impact on the situation.

The information policy on the prevention of extremism has focused on promoting narratives that are of little interest to young people. Although progress in this direction is noticeable, the main problem remains the blurring of the messages being promoted. This produces a situation where everyone who implements the policy independently chooses in which direction to work. This has allowed for the emergence of discriminatory messages and hate speech.

Another problem is the state’s desire to have a monopoly on religious truth: official religious institutions, as “allies” of the state in countering religious extremism, try to impose their ideas on a large number of young people. This situation creates distrust of religious leaders, who, in the eyes of the public, are inextricably linked to—and practically “service providers” of—the state. (This also works in the opposite direction: the lack of professionalism of “affiliated” clergy can cast a shadow on local and central authorities.)

In general, studies show that young people today still have a high level of loyalty to the state and government policy (especially policy related to ensuring national security). At the same time, young people increasingly value justice, personal rights, and freedoms, leading them to demand increased participation in the affairs of government and local communities.

Under such conditions, policymakers should reconsider attitudes regarding the place and role of youth in the prevention (and countering) of violent extremism. Such cooperation is beneficial to both parties and can bring PVE in the country to the whole-of-society level toward which the global leaders in PVE are striving today.

Policy Recommendations

I suggest here the following changes to Kazakhstani P/CVE policy targeting youth:

- Promoting youth participation (especially among “vulnerable categories”) in PVE efforts

- Supporting youth activism and civic engagement; strengthening the capacity of youth organizations through the provision of trainings and creation of a supportive climate

- Building driver-based policy and overcoming youth marginalization, considering local context

- Involving local authorities, civil society, and the private sector in efforts to strengthen youth resilience

- Deepening the understanding of how “best practices” from other states and regions should be adapted to the Kazakhstani context

- Improving data collection and establishing criteria for measuring the impact of efforts undertaken.

In 2022, Kazakhstani policymakers will face the need to adjust PVE policy, as the current state program will conclude in December 2022. In making such adjustments, they will need to pay attention to the following system-level problems that define the frame of the policy:

- First, the term “violent extremism” should be incorporated into Kazakhstani legislation. This will help to distinguish between convictions and intent to engage in violence, allowing for a clearer focus on PVE policy.

- Second, the prevention of VE requires de-securitization. Today, since the main operator of the state program is the National Security Committee, the majority of activities in this field are classified, with the result that it cannot be definitively stated whether PVE is effective or ineffective.

- Third, measurable and unequivocal indicators should be implemented in PVE policy; the effectiveness of counter- and alternative narratives should be verified.

- Fourth, mechanisms for independent monitoring and evaluation need to be included in all state-driven PVE activities.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to Dr. Marlene Laruelle for her supervision and encouragement. I would also like to thank Serik Beissembayev for his advice and support during the research process, and Anel Serikbek, Maral Shyndaulova, and Gulmira Olchikenova for their assistance in data collection and processing.

[1] “Sostavlen sotsial’nyj portret terrorista v Kazakhstane”, Tengrinews. September 9, 2016, https://tengrinews.kz/crime/sostavlen-sotsialnyiy-portret-terrorista-v-kazahstane-253308/.

[2] Lorne L. Dawson, “Sketch of a Social Ecology Model for Explaining Homegrown Terrorist Radicalisation,” ICCT Research Note (2017). Doi: 10.19165/2017.1.01.

[3] Olivier Roy, “France’s Oedipal Islamist Complex,” Foreign Policy, January 7, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/01/07/frances-oedipal-islamist-complex-charlie-hebdo-islamic-state-isis/.

[4] “Voevat’ na storone IGIL vyekhali okolo 400 kazahstantsev s chlenami semei”, Ratel.kz, June 18, 2015, https://www.ratel.kz/raw/voevat_na_storone_igil_vyiehali_okolo_400_kazahstantsev_s_chlenami_semey.

[5] USAID, “The Development Response to Violent Extremism and Insurgency: Putting Principles into Practice,” USAID Policy, September 2011, p.2.

[6] Center for the Prevention of Radicalization Leading to Violence, “The Radicalization Process,” accessed September 29, 2021, https://info-radical.org/en/radicalization/the-radicalization-process/.

[7] Georgia Holmer and Peter Bauman, Taking Stock. Analytic Tools for Understanding and Designing P/CVE Programs (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2018).

[8] [8] USAID, “The Development Response to Violent Extremism and Insurgency: Putting Principles into Practice,” USAID Policy, September 2011, p. 3.

[9] USAID, “Atrocity Assessment Framework. Supplemental Guidance to State,” 2009, accessed September 29, 2021, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/241399.pdf.

[10] On Countering Extremism. The Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated 18 February 2005 No. 31.

[11] United Nations General Assembly, “A/HRC/28/66/Add. Report of the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief,” Heiner Bielefeldt, 2015.

[12] United Nations General Assembly, “A/70/674 Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism,” 2015.

[13] Moussa Bourekba, “Overlooked and Underrated? The Role of Youth and Women in Preventing Violent Extremism,” Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB) Notes (2020): 240.

[14] I. Idris, “Youth Vulnerability to Violent Extremist Groups in the Indo-Pacific,” GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1438, University of Birmingham, 2018.

[15] United Nations, “Recommendations of the Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism,” n.d., accessed September 29, 2021, https://www.un.org/sites/www.un.org.counterterrorism/files/plan_action.pdf.

[16] Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan Bureau of National Statistics, https://stat.gov.kz.

[17] A. Ivanilova, “V Kazahstane rastet dolia ne rabotaiushchei i ne uchashcheisya, Moskovskii Komsomolets Kazakhstan, November 10, 2020, https://mk-kz.kz/social/2020/11/10/v-kazakhstane-rastet-dolya-ne-rabotayushhey-i-ne-uchashheysya-molodezhi.html.

[18] Zh. Bukanova, Zh. Karimova, L. Amreeva, L. Zainieva et al., “National Report ‘Youth of Kazakhstan—2014” (Astana: “Youth” Research Center, 2014), 152.

[19] “National Report ‘Youth of Kazakhstan—2020” (Nur-Sultan: “Youth” Research Center, 2020), 376.

[20] “Srednii vozrast izbrannykh deputatov senata Kazahstana—56,5 let”, Zakon.kz, August 20, 2020, https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=31044194.

[21] V. Abramov, “Obnovlennyi mazhilis: men’she chinovnikov, bol’she obshchestvennikov”, Vlast.kz, January 18, 2021, https://vlast.kz/politika/43403-obnovlennyj-mazilis-mense-cinovnikov-bolse-obsestvennikov.html.

[22] “Molodym vezde u nas doroga? Srednii vozrast regional’nykh akimov v RK—55 let”, Ranking.kz, May 4, 2021, http://ranking.kz/ru/a/infopovody/molodym-vezde-u-nas-doroga-srednij-vozrast-regionalnyh-akimov-v-rk-55-let.

[23] A. Gorbunova, “140 kazahstantsev osuzhdeny za terrorizm i ekstremizm v 2019, Forbes Kazakhstan, December 12, 2019, https://forbes.kz/process/probing/140_kazahstantsev_osujdenyi_za_terrorizm_i_ekstremizm_v_2019/.

[24] M. Baigarin, “V Kazahstane s nachala goda 32 cheloveka osuzhdeny za terrorizm”, Kazinform, August 20, 2020, https://www.inform.kz/ru/v-kazahstane-s-nachala-goda-32-cheloveka-osuzhdeny-za-terrorizm_a3685594.

[25] Anna Gussarova, “Features of Countering Violent Extremism and Terrorism in Kazakhstan,” Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting, November 22, 2019, https://cabar.asia/en/features-of-countering-violent-extremism-and-terrorism-in-kazakhstan.

[26] World Health Organization, How to Develop and Implement a National Drug Policy, 2nd ed. (New York: WHO, 2001), 77.

[27] See Justin Beaumont and Christopher Baker, eds., Postsecular Cities. Space, Theory and Practice (London: Continuum, 2011).

[28] Bruce Pannier, “Ne naidia v mecheti soveta, kak vyzhit’ segodnia, molodezh’ popadaet k islamistam”, Radio Azattyq. April 1, 2010, https://rus.azattyq.org/a/central_asia_islam_youth/1998917.html.

[29] A. Kassenov, “Molodezh’ neverno ponimaet znachenie slova ‘patriotizm’—mnenie, Tengrinews, May 30, 2016, https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/molodej-neverno-ponimaet-znachenie-slova-patriotizm-mnenie-295412/

[30] Dossym Satpayev, “Political Risk Management in Kazakhstan,” in Transformation of the Economy of Kazakhstan (Astana: IndigoPrint, 2019), 125.

[31] Joanna Lillis, “Kazakhstan: Waking Up to Reform,” Eurasianet, June 11, 2019, https://eurasianet.org/kazakhstan-waking-up-to-reform.

[32] Serik Beissembayev, “Pushkoi po vorob’iam. Pochemu v Kazakhstane ne effektivna profilaktika religioznogo extremizma?” Vlast.kz, June 17, 2016, https://vlast.kz/politika/17906-puskoj-po-vorobam-pocemu-v-kazahstane-ne-effektivna-profilaktika-religioznogo-ekstremizma.html.

[33] “Religioznaia gramotnost’—faktor stabil’nosti”, KazInform, May 23, 2021, https://www.inform.kz/ru/religioznaya-gramotnost-faktor-stabil-nosti_a2912312.

[34] Anastassiya Reshetnyak, “Terrorizm i religioznyi ekstremizm v Tsentral’noi Azii: Problemy vospriiatiia Keis Kazakhstana i Kyrgyzstana” (Astana:KazISS under the President of RK, 2016), 12-14.

[35] Ibid.

[36] “Obuchaiushchii kurs dlia spetsialistov religioznoi sfery po ‘kopirajtingu’, ‘targetingu’ i ‘SMM’,” Center for Religious Studies of Nur-Sultan, accessed September 29, 2021, https://elorda-din.kz/ru/novosti/obuchayushhij-kurs-dlya-specialistov-religioznoj-sfery-po-kopirajtingu-targetingu-i-smm.html.

[37] “Prokuratura Nur-Sultana zapuskaet konkurs ‘Vmeste protiv ekstremizma’”, Akimat of Nur-Sultan, November 11, 2020, https://astana.gov.kz/ru/news/news/25174.

[38] “Po millionu tenge poluchili pobediteli konkursa ‘Vmeste protiv ekstremizma’”, Smart Astana, December 25, 2020, https://api.smart.astana.kz/ru/news/3389/.

[39] A series of operations conducted by the Kazakhstani security forces aimed at bringing citizens of Kazakhstan (mostly women and children) home from Syria in 2019.