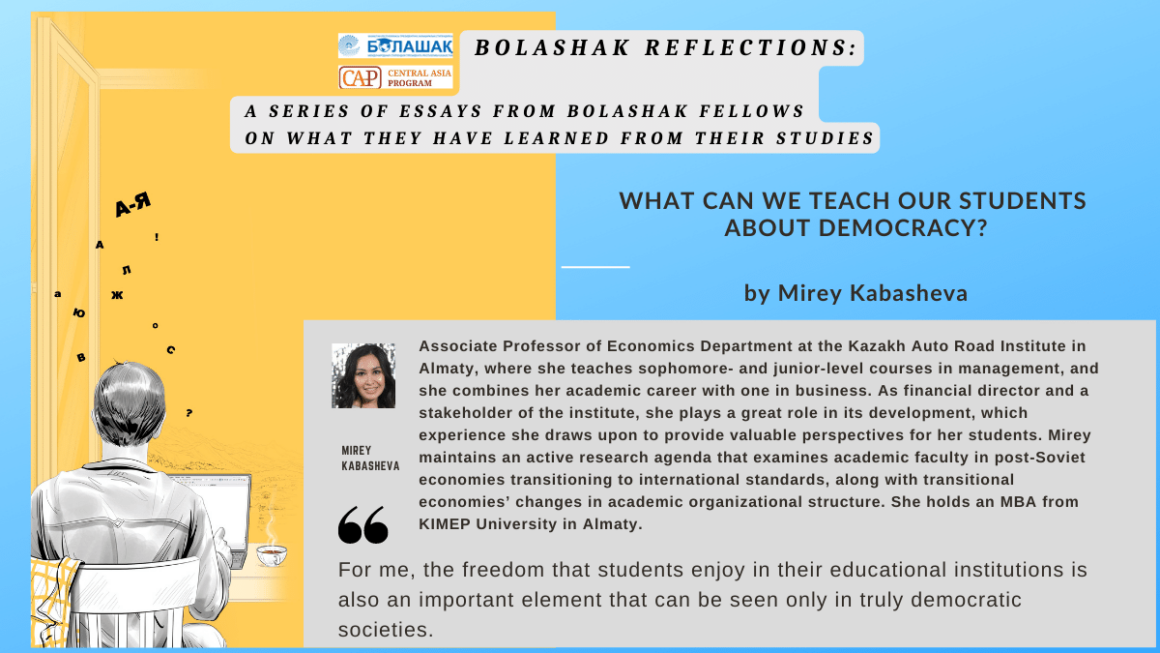

Bolashak Reflections: A Series of Essays from Bolashak Fellows on What They Have Learned from their Studies.

Author: Mirey Kabasheva

A few days ago, I and my fellow friend from the Bolashak Leadership in Education Fellowship Program at George Washington University took a walk through the city. We were headed to Georgetown University on a site visit. It was nice fall weather in Washington, DC as we walked through the intersection of Wisconsin Avenue and O Street, with beautiful Victorian houses, where every door was decorated for the upcoming Halloween festivities. Yet when we approached Healy Hall, Georgetown University’s main building, and its picturesque courtyard with an enormous sycamore tree and students walking around and chatting, we got to see a particular atmosphere of the university: peaceful yet vibrant. Whoever I come here with, I always hear one question: “Why do I feel so free here?”

And that question stayed with me for weeks. I started to remember my feelings in all the campuses of American universities I had ever been to. Gorgeous and prim Harvard, innovative and fast-moving MIT, oceanic and relaxed UC San Diego, and traditional and ambiguous UPenn. Surprisingly, they all evoked the same feeling of freedom. While trying to dissect what this vague concept of freedom means, I found that it has many components: being free about how you look and what you say but respecting boundaries, both yours and others; openly showing emotions and feelings but also complimenting others on their success; and asking questions and listening to others. For me, the freedom that students enjoy in their educational institutions is also an important element that can be seen only in truly democratic societies.

Why is democracy important for education?

Democracy is taught – it is not innate

According to Larry Diamond (2004), democracy consists of four basic elements: 1) a political system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; 2) the active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; 3) the protection of the human rights of all citizens; and 4) the rule of law, in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens. Classifying which country is more democratic that another is still controversial.

For post-Soviet people and the people of Kazakhstan the definitions of democracy, its measurement, research, current studies, and controversy are still a gray area. Democracy is not being taught in our schools and I suspect is poorly taught in our universities!

The aspect I wanted to emphasize in my essay is the role of educational institutions in the spread and development of democracy in the country. That feeling of freedom you feel visiting the American universities I could finally explain after I had read the book by Ronald J. Daniels, What Universities Owe Democracy. Still serving as president of the US’s first research-oriented educational institution, Johns Hopkins University, the author openly discussed the lack of knowledge of democracy by his students. Having high SAT scores, being taught in one of the best colleges in America, students nonetheless showed low civic literacy levels. And Daniels felt responsible for researching this situation further and offering possible ways to resolve the issue.

What is a “citizen,” for example? This category was invented in ancient Greece. The idea of the holistic person was defined in the concept of paideia, when a citizen had to be multilateralist, taking part in political debates, singing in a chorus, acting in tragedies by Sophocles, and defending his will. Being a citizen is not an innate feature; it should be cultivated in society. The best line in this regare cited in the book is a quote from the former US Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor that “the practice of democracy is not passed down through the gene pool.”

Daniels argues that civic education should be started in school (grades K–12). According to research, there is a direct correlation between civic knowledge and the highest liberal democracy indicators. In Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Estonia, schools showed the best indicators in civic education surveys among school students. And people who participate in elections and are able to reason their opinion had a good knowledge of civic democracy obtained during their school years.

The author is critical towards schools’ civic education in the US. He emphasizes the lack of this kind of knowledge provided by American schools. I definitely agree that there is inequality and some kids do not have access to high-quality education as grade-school students, and the US school system is diverse, unevenly distributed, and challenging. However, I would like to add my experience to this issue. My son is a 3rd-grade student in the DC public schools. One of his first homework readings was dedicated to the American government’s organizational structure. “The U.S. government isn’t a tree, but it does have branches” – says the passage written for 3rd-graders. I couldn’t even remember when in my life I got to learn this. Maybe it was in the Political Science (Politology) class in my freshman year in college. For many people who move to the US from different parts of the world this knowledge is important as are civic values. A curriculum that contains the studies of the foundations of democracy is a tiny step to enlighten a child who came from an authoritarian country.

Sadly, we don’t get to feel the freedom that I have described at the beginning of my essay in Kazakh schools and universities. These institutions in general are publicly-funded, employ a lot of people who receive wages from the state budget, and as such they are governmental instruments of control and supervision. Burdened with hard bureaucracy, rigid rules, and regulations that come from the regional and local executive bodies (akimats and their departments), old-time traditions of having to be seated firmly in one place and being afraid to speak up, our schools and universities are hardly a free space for vibrant debates and intellectual vigor.

Another point I want to discuss is academic autonomy. US universities have tenured professors. Professors, who are like the US Supreme Court or other federal judges, are chosen by the academic councils to be lifelong appointments by the university. The analogy with the Supreme Court is not random. Federal judges have lifelong tenure in order for them to not be afraid to issue a ruling that could be truly impartial, albeit politically controversial, for any stakeholder in a given case. Likewise, professors for being academically honest should have the guarantees that they will not be fired after publishing their scientific research. Thus, academic honesty in a university allows universities to be autonomous, to shape curriculum as they see fit. The feeling of freedom and liberty in American universities compared to in their Kazakhstani counterparts lies in the academic autonomy and honesty of learning institutions.

Ways to get out of the trap

President Daniels in his book considers how educational courses on democratic citizenship and literacy should be designed. He proposes to include such competencies as “critical and quantitative reasoning, a knowledge of political history, and the discussion of urgent social issues,” along with the skill of practicing the “art of peaceful protest to enact change.” This knowledge should be available to all students, not only those who are enrolled in social sciences and are eager to learn about political science. Universities should be aware of their responsibility in training their students in democratic citizenship regardless of where they come from, their major, or their financial status.

Even though democratic literacy rates are sometimes criticized in the US, university environments here still differ greatly from those in my home country in this regard. And every time when I want to experience that feeling of freedom again, I take a stroll by my favorite O Street. And I always wonder what we can bring back home after the Fellowship Program that could lead to some quick results in the improvement of education. Obviously, education is an area where results from changes cannot be seen immediately, and this is why politicians who worry about the need to point to short-term successes so often fail at reforming education.

My takeaway from reading Daniels’ book, from talking to my colleagues and professors, and simply from strolling down O Street is that we could give our own students back home something more basic and essential. Teaching them how to be bold in their thinking and writing, in their choosing what to read and learn, understanding that such freedom is only possible in a system that puts equality above all—this will help us to finally propagate the value of education and research on the governmental level. In today’s uncertain world, only those open to knowledge and free thinkers are able to crack the code of prosperity and well-being for the nation.

References

- Ronald Inglehart, “How Solid Is Mass Support for Democracy—and How Can We Measure It?” Political Science & Politics 36, no. 1 (January 2003): 51–57, https://www.proquest.com/docview/224926703?accountid=11243&parentSessionId=uBiGdqAxiUDscb45N8vFeuSCKtJ%2FD3nzSNK4AKxIFZE%3D&pq-origsite=primo.

- “Three Ways to Frame and Measure Democracy,” University of Pennsylvania, Center for High Impact Philanthropy, https://www.impact.upenn.edu/democracy/three-ways-to-frame-and-measure-democracy/.

- Herre, Bastian, “Democracy Data: How Do Researchers Identify Which Countries Are Democratic?” Our World in Data, June 17, 2022, https://ourworldindata.org/democracies-measurement.

- Daniels, Ronald J., with Grant Shreve and Phillip Spector, What Universities Owe Democracy (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021), esp. p. 90.