By Elmurat Ashiraliev

Elmurat Ashiraliev is currently an independent researcher. He was a Visiting Fellow at the George Washington University’s Central Asia Program in Spring 2019. Prior to joining CAP, Elmurat worked as a journalist based in Bishkek. He earned an MA in Central Asian Studies from American University of Central Asia.

Abstract

In August 2019, a conflict broke out among local people in Abdraimov Village in the Kyrgyz Republic’s southern Jalal Abad province. Some 50 villagers opposed the construction of a Kingdom Hall, a place of worship for Jehovah’s Witnesses. Gathering in the yard of the Kingdom Hall, the villagers insisted that the Jehovah’s Witnesses stop the construction work. Some protesters demanded a complete shutdown, while others insisted on seeing papers authorizing construction before allowing them to proceed with their work. The Jehovah’s Witnesses were not physically attacked, but tensions reportedly rose high.

Religious conflicts are not new to Kyrgyzstan. Since its independence, the country has witnessed several similar incidents. To regulate the religious realm, the Kyrgyz Republic established the State Commission for Religious Affairs (SCRA), the central body that develops and implements state policy in the religious sphere and coordinates other state institutions’ activities in this field.

Since then, the SCRA has registered about 3,500 religious organizations, the majority of which (around 3,000) are mosques and madrasas, while the rest belong to religious minorities. This seems to be more or less proportional to general religious representation in the country. Sunni Muslims comprise an estimated 80–90% of the country’s population, with the rest being religious minorities or non-believers.

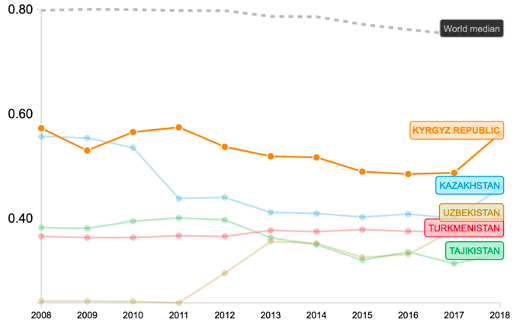

The 2019 Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices database on the freedom of religion[1] lists Kyrgyzstan among the mid-range-performing countries, whereas the other Central Asian states are designated as low-performing (see Figure 1). However, all Central Asian countries, including Kyrgyzstan, have been performing below the global average for the nearly 30 years since their independence.

This paper focuses on the challenges that religious minorities face in Kyrgyzstan. Jehovah’s Witnesses have long been on the radar of the Kyrgyz authorities and the international community as well as mass media. They are one of the few religious communities that has sued the SCRA when the state institution has refused to register their communities in regions where they have been facing problems due to their door-to-door proselytizing activities.

This paper explores the lives of the Witnesses in rural Kyrgyzstan. It is an attempt to delve into the meaning of being a member of a religious minority and how freedom of belief and religion play out in remote areas. The Witnesses are not the largest religious minority in the country, however. These are various Protestant denominations and Orthodox Christians, while other religious minorities that are represented include the Baha’i Faith, Shiites, and Buddhists.

Figure 1. Freedom of Religion Ranking for Central Asia

This paper is based on interviews with Witnesses, other villagers, village- and district-level authorities, and SCRA officers conducted during a one-month fieldwork exploration in Abdraimov Village, where a conflict occurred a year ago.

Kyrgyzstan’s Religious Minorities

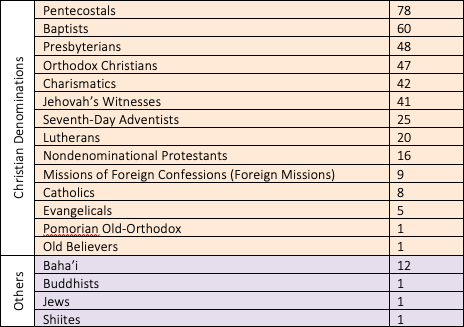

The Kyrgyz Republic is home to a number of different ethnic groups. According to the Kyrgyz National Statistics Committee, as of 2020 the population exceeded 6.5 million people, about 70% of whom are ethnic Kyrgyz. The largest ethnic minorities are Uzbeks (15%) and Russians (5%). Kyrgyz and Uzbeks are primarily Sunni Muslim, while Russians are generally Orthodox Christians. But the religious landscape of Kyrgyzstan is more diverse. Currently, there are more than 400 registered religious communities in the country, the majority of which are affiliated with different Christian denominations (as illustrated in Table 1).

Table 1. The Number of Minority Religion Organizations in Kyrgyzstan

In 1991, the Constitution of the independent Kyrgyz Republic guaranteed freedom of religion to its citizens and clearly separated state institutions from religious ones, underlining the Republic’s secularism. Article 32 of the Kyrgyz Constitution guarantees (1) freedom of conscience and belief, (2) the right to confess or not to confess any religion individually or jointly with others, (3) the right to freely choose and have religions and other convictions, and (4) the right not to be forced to express or deny one’s religious and other convictions.

Further, Kyrgyzstan is distinguished from its neighbors by its relatively liberal religion laws (officially called the Law on Freedom of Religion and Religious Organizations), which have contributed to the free existence and development of the religious sphere.[2] As a result, many foreign religious organizations have settled in the country, laying the foundations of today’s religious pluralism. We see from the statistics presented in Table 1 that the majority of religious organizations are affiliated with Protestant denominations.

This does not mean, however, that religious diversity is limited to the emergence of Christian denominations. Muslim communities have also experienced internal pluralism due to Kyrgyz citizens’ travel abroad (to Turkey, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, etc.) for Islamic education and the arrival of foreign Islamic religious organizations that have come to work in the country.

The freedom of the religious realm was not interrupted until the mid-2000s. The first state policy concept on the religious realm was adopted in 2006 and was followed by the adoption of amendments to the religion law. With the new law, tighter control over religious organizations was introduced. For example, to register a community as a religious organization, the law required the group to provide a list of 200 Kyrgyz citizens as founding members and to get the list approved by the local council. Previously, a list of ten members had been sufficient to get official registration and the approval of the local authorities had not been necessary. This change had a profound effect on members of minority religions such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

In 2014, the second state concept was developed and was to be in force until 2020. The third concept is under public discussion and review at the time of writing and will navigate the direction of the next six years (2021–2026). The main aspects of the policy concept include improving the religion laws, developing information policy in the religious sphere, promoting cooperation among religious organizations and state institutions, and advancing theological and religious studies, among other aims.

To work in the religious sphere, Kyrgyz laws require each entity to receive official registration from the State Commission for Religious Affairs (SCRA). This registration gives the organization the right to practice, preach, and propagate religion in certain places permitted by law. For instance, the religion laws ban the distribution of religious literature in public spaces, educational institutions, and houses. The organization of charitable activities to spread the faith is also prohibited. In general, religious organizations are free to practice and spread their faith within the limits defined by the religion law.

There is no census data by religious affiliation in Kyrgyzstan, making statistics difficult. According to some estimates, the number of Protestant Christians ranges between 15,000 and 30,000, at least half of whom might be ethnically Kyrgyz.[3] Kyrgyz Christians, particularly Kyrgyz converts, usually face persecution or harassment in society, especially in the regions, where Kyrgyz identity has historically been associated with Islam. Ethnic Kyrgyz who practice a faith other than Islam are often perceived negatively and eventually ostracized.

In this paper, I mostly discuss the issues of Kyrgyz converts, who make up a large portion of the membership of minority religions, as they are more likely to experience difficulties such as social exclusion, discrimination, and harassment in their everyday lives. Moreover, from time to time, members of minority religions have been cut off from irrigation channels or refused tractors and combine (harvester) services, thus causing them to face economic harm.[4] Some of the urgent issues concerning Kyrgyz converts are physical assaults and the issue of burials, among others.[5] There have also been cases where local people have protested against the construction of a place of worship of a minority religion, or even damaged and burned parts of prayer houses.[6]

Jehovah’s Witnesses in Kyrgyzstan

The Jehovah’s Witnesses came to the territory of present-day Kyrgyzstan as early as the 1950s and received their official registration in 1998.[7] According to Alymbek Bekmanov, Chairman of the Jehovah’s Witnesses Religious Center in Bishkek, there are currently about 5,000 Witnesses in the country, the majority of whom are Kyrgyz converts.

The Witnesses have 41 religious communities registered (all before the 2008 law) across the country, most of which (34) are concentrated in the capital city of Bishkek and the surrounding area (Chuy Province). There are four communities in Issyk Kul, one in Talas Province, and one each in the towns of Toktogul and Kochkor. Since 2010, requests to register new communities in four other provinces—Batken, Jalal Abad, Naryn, and Osh—have been repeatedly denied.

As mentioned above, the 2008 religion law—particularly the requirement to produce a list of 200 founding members and get it approved by the local council—impacted the Witnesses. In several regions, the lists were not approved by the local councils, with the result that the Witnesses applied to the district-level court and then appealed the decision in inter-district and regional courts as well as the Supreme Court.[8] Upon the Witnesses’ application, the Constitutional Court of Kyrgyzstan declared unconstitutional the requirement to have a list of 200 members approved by the local council. Due mainly to state bureaucracy, corresponding amendments were introduced into law only in 2019. According to the new law, registration of religious organizations is centrally managed by the SCRA and the approval of local councils is no longer required.

Bekmanov suggests,

We, the Jehovah’s Witnesses, do not seek such difficulties. Just one example, the Witnesses in Russia are persecuted. Russia banned it as an extremist organization in April 2017. At the same time, be it in the US, France or here, we are relatively free. […] In some countries, where the Witnesses are banned, they are not able to apply to courts or to the police. Despite that, they try to maintain their security and protect their faith. Compared to them, we have way better conditions. We can apply to courts, state authorities. We can express our ideas. But it may not be this way forever. Circumstances may change one day. So, God’s nation has survived hard days, thus they have experience from the past. […] Imagine, even during Nazi Germany, God’s Word was spread throughout the prisons. The messages were extensively disseminated across Germany, particularly while Hitler was in power. Hitler declared that he would wipe the Witnesses, like the Jews, from the face of the earth. Therefore, from the outset the Witnesses were put in the concentration camps together with the Jews.[9]

Before the religion law was amended in 2019, there were several court cases involving the Witnesses, all because different regions refused to register their communities.[10] As Bekmanov explains, according to their internal regulations, when the Witnesses received official registration in 1998, that registration contained a provision that gave them permission to work not only in the capital city of Bishkek, but also across the country. Accordingly, they consider that they do not need to receive additional registrations in Batken, Jalal-Abad, Naryn, and Osh, but attempted to do so under pressure from local authorities and due to the necessity of protecting their members.

After the new law came into force, the Witnesses made another attempt, this time under the new regulations, to register their regional congregations. The SCRA rejected the request. The Witnesses appealed the case to the Supreme Court, but they lost. Overall, for the past ten years, the Witnesses have been suing the state authorities at different levels and have been in constant tension with them.[11] In a sense, the Witnesses’ case resonates with Anthony Gill’s propositions on the political origins of religious liberty:

Hegemonic religions will prefer high levels of government regulation (i.e., restrictions on religious liberty) over religious minorities. Religious minorities will prefer laws favoring greater religious liberty. […] Regulatory policy toward religion is likely to favor the dominant church and discriminate against minority denominations.[12]

Bekmanov explains,

We have been trying to register in Jalal Abad Province since 2010. Then again in 2013, 2014, and the most recent one is in court. In the past, we also appealed to the UN; it obligated [the Kyrgyz Republic] to register [us]. In 2014, the Constitutional Court [of the Kyrgyz Republic] likewise declared unconstitutional the requirement to get approval from local councils for the registration of religious organizations; they [the Constitutional Court] even said that registration was not required. Due to issues with officials in the provinces frequently stopping [our members] and asking if they have registration, we have had to get official registration for our communities. This is the fourth attempt and now it is in court.[13]

As pointed out above, religious organizations are not allowed to propagate their faith in public spaces, educational institutions, or houses. Although this prohibition had an impact on the Witnesses, it did not stop them from spreading their teachings. Bekmanov defends himself by saying that they do not bring materials with them in their door-to-door missionary work. But if people invite them to their houses, they do not decline the invitations.

Beyond legal difficulties with registration, it is the issue of ethnic Kyrgyz converts that creates the most tensions on a daily basis.

Jehovah’s Witnesses in Abdraimov

Abdraimov village is located 535 km to the south of Bishkek. With a population of 13,000, Abdraimov is one of the largest villages[14] in the country and is home to about ten different ethnic groups. The majority of residents are Kyrgyz (85%), with the rest being Uzbeks (14%), Uyghurs, Tajiks, and Russians, among others. Abdraimov is not far from Bazar Korgon Administrative District Center: the trip takes around ten minutes by car, which means the village is not isolated. Located along the Bishkek-Osh highway and the highway to Arstanbap (Arslanbob) walnut forest, Abdraimov is one of the busiest places in the area. Locals make a living from agriculture. There are also small businesses such as cafés, retail, taxi services, establishments employing wage workers, and so on. The Jehovah’s Witnesses congregation in the village has about 50 members. The majority are scattered around Abdraimov, but there are also some members who join the congregation from neighboring villages. There are no foreign missionaries among them: all are Kyrgyz converts.

Kingdom Hall, which sparked the outcry among residents mentioned in the introduction, is located in the middle of Abdraimov. One cannot distinguish it from neighboring houses, as it looks like an ordinary residence: the yard of the house is almost obscured by the tall brick walls and white metal gates. The only visible features are its metal roof and the nut trees that grow around almost every home in the village.

Due to quarantine restrictions, I was not able to meet with the Jehovah’s Witnesses in person. After a two-month negotiation, I was given permission to talk to one of their Abdraimov-based members over the phone. My interview was conducted on WhatsApp video calls in the presence of Bekmanov. My main interlocutor wished to remain anonymous, so I will call him Erkin.

Photo taken by the author in July 2020.

A Conflict in the Village

Erkin was born and lives in Abdraimov, and his neighbors are not Jehovah’s Witnesses. Unlike some of his neighbors, who live in two-story brick residences, he lives with his wife in a modest one-story house. Except for his elder brother, everyone in his family is a Jehovah’s Witness, including his mother and three sisters, who live in the neighboring town about 25 km away. His father passed away several years ago. According to Erkin, there are about fifty Jehovah’s Witnesses in the village, and like Erkin, they are all converts who were born and raised in Muslim families.

Erkin’s mother was the first to convert to the Jehovah’s Witnesses; she converted in the early 2000s, when they were working in Bishkek. Soon afterwards, Erkin, who was then in his mid-20s, converted. “Before, I used to be a Muslim. I used to go to the mosque. I also went through it [opposed other villagers’ conversion]. When I first heard from my mother [that she had converted], I objected, saying Mom, why would you do that? We are Muslims! How can we do it while we are Muslims?” My dad objected, too. After reading the Holy Book [Bible] we all realized that it is all true,” Erkin says, recalling his conversion.

Erkin’s family returned to Abdraimov in the mid-2000s. Upon arrival, his mother started preaching to their neighbors. Some related to her teaching, while others did not. Later, with some five people, they started to congregate in their house. Erkin remembers:

I used to hold several congregations at our place. When we first started preaching, it was good. People used to say that it turns out God’s Word is great; it turns out that it is useful for us to read [God’s Word]. Later, perhaps hearing gossip that they [Jehovah’s Witnesses] are different, they sold out their religion, people disputed with each other, one group supporting and others opposing us. From that time on, some villagers started to protest and argue with us.

Neighborly relations appeared stable up until August 2019. The local Jehovah’s Witnesses had bought a residential house in the middle of the village and were working on rebuilding it to make it a place of worship.

I guarded the Kingdom Hall overnight. That morning, when I left home to collect vegetables, my wife called me. She told me that people had gathered and were protesting in the Kingdom Hall. I went back right away. When I tried to greet them and ask if I could help, they did not listen to me but verbally attacked me, shouting, “This is their leader, they brought it here first!” I asked what the matter was and why they were shouting.

To prevent the situation from escalating, Erkin reacted calmly and responded as patiently as possible. He recognized faces among the people who had gathered. Some of them were his neighbors.

They [my neighbors] went there to shut down the construction of the hall. There was a bearded man who lived near our hall. He was quite agitated and organized much of the scuffle. […] I had my own investigation.

Back then, the circumstances were difficult for all Jehovah’s Witnesses. Fortunately for other Witnesses (and unfortunately for Erkin), he alone had to overcome much of his co-villagers’ resentment, as he is from that neighborhood and is quite well-known there.

The way his co-villagers and some village administration officials behaved frustrated Erkin, because he had expected a neutral attitude—particularly from the local authorities. But the village officials entered the yard of Kingdom Hall with all the protesters, who spoke loudly and did not want to hear Erkin out. Instead of standing on the side of the law, which is meant to treat all citizens equally regardless of their faith, the local authorities expressed their position, Erkin explained, as “What the [opposing] people say is right. I am with the people.” Protesters demanded the closure of the hall, though they did not use physical violence.

It would be good if it happened according to rules. They could wait near the gates and ask if we could talk. But in the village, this is impossible. Many do not understand the issue here. They invade without knowing exactly what is happening.

Following the protest, a district-level commission was to decide the fate of the Kingdom Hall. The commission included Bazar-Korgon District administration officials, Abdraimov officials, and officers of the State Commission for Religious Affairs, the State Agency for Interethnic Relations, and law enforcement agencies. It took a month for the commission to examine the case and decide it, during which time the Jehovah’s Witnesses were told to pause activities in the village. In September 2019, the commission decided that the Witnesses did not have the necessary documents for the construction of the Kingdom Hall and that their activities would be suspended until they received permission from the relevant entities.

This decision, which was intended to calm down the opposing residents, did not convince the Jehovah’s Witnesses. On the contrary, they felt discriminated against and deemed the decision unjust. They claim that they try to be law-abiding citizens and always take care of the bureaucratic procedure first. Thus, soon after the conflict was defused, they continued building, and by December 2019 they had finished construction of the Kingdom Hall. The Witnesses congregated there until mid-March 2020, when lockdown measures were enforced worldwide by their Governing Body in New York due to the coronavirus pandemic. Since then, the Kingdom Hall in Abdraimov has been locked and I was not able to enter. Like elsewhere in the world, Kyrgyz Jehovah’s Witnesses stopped having face-to-face meetings and switched to online activities. According to their internal regulations, if the public health situation returns to normal, Kingdom Hall will be open by the end of February 2021. If the situation remains unchanged, the quarantine restrictions will be extended until further notice.

Before moving to the new Kingdom Hall, the Witnesses used to congregate in rented buildings on the outskirts of the village. Although the previous buildings were located outside the village, there were some problems with residents who lived nearby. On several occasions, the windows of their prayer houses were damaged, the doors nailed up, or the furnace stolen. The Witnesses did not want to complain to law enforcement, deeming the actions insignificant. They decided to file an application only after an incident in which someone trespassed on their building site and burned some of their religious literature. But the trespasser was not found.

Local Authorities

Abdraimov Village officials have varying stances on the Witnesses. Some officers did not want to talk to me about the community, excusing themselves by reference to their busy schedules, while others were open to having a conversation. For instance, one village official told me that the Witnesses visited him once at his house and gave him some of their religious literature (books, journals, and other publications). But he said that it was difficult for him to read and understand the literature on his own. As he knows Erkin personally and they grew up together in the same neighborhood, he tries to retain the relationship of a co-villager with Erkin. Since the village officer has not talked much to the local Witnesses, nor has he attended their congregations, he has rather limited knowledge of Erkin’s and other Witnesses’ worldviews. Thus, like other villagers, he makes unfounded assumptions about the Witnesses.

Some of the high-ranking officers of the Bazar-Korgon District administration are also from Abdraimov. In general, the local authorities at both village and district level have limited information on the Witnesses, making it difficult for them to make informed decisions on certain issues. It is also worth noting that mutual understanding and communication between the local government and the religious community has yet to be established.

Although Erkin and his co-religionists are Kyrgyz citizens, they are treated as if they are foreign to the village. As indicated in previous sections, the idea that being Kyrgyz also means being Muslim is widespread among local people and prevails among the authorities as well. As a result, a non-Muslim Kyrgyz is more likely to be ostracized and denied the authorities’ attention in the regions. Religious minorities’ choices are not always respected by the local authorities, much less the general public.

What Do People Say?

Since converting to the Witnesses, Erkin says, he has not experienced big problems. The most unexpected and largest conflict was the one around the Kingdom Hall last year. Let us now explore what Erkin’s fellow villagers think of the Witnesses and what their interactions look like.

Opinions about Jehovah’s Witnesses in Abdraimov diverge. In terms of their attitude, the people I met can be grouped into three categories: neutrals, opponents, and silent supporters. However, the majority seem to share a negative attitude toward Erkin’s co-religionists. Talking with randomly encountered local people about Witnesses in their village suffices to get a sense of such an attitude.

When asked, almost everyone I encountered in Abdraimov touched on the issue of village gatherings and the Jehovah’s Witnesses. “They do not go to funerals, they do not cry if one dies, this religion seems so odd,” one of Erkin’s neighbors says, adding, “When Erkin’s father died, they did not cry and just buried him.”

I talked to four out of seven of Erkin’s close neighbors, and their stances are similar. They all maintain a good-neighborly relationship with Erkin’s family. Although they think of Erkin and other Witnesses as harmless people, they do not understand why they do not join in village get-togethers as local traditions dictate. Erkin and his co-religionists are perceived as disrespectful to Kyrgyz customs and traditions. Other villagers’ view might be summarized as follows: “They are good, but they do not go to the funerals and if they do go, they do not cry at funerals.”

This type of us-versus-them narrative can be regarded as the least destructive in the community, because it remains at the level of words and thoughts. The people I met in Abdraimov who shared this view came from different backgrounds—teachers, imam assistants, peasants, etc. They often had a neutral attitude toward, and might also have expectations of, Jehovah’s Witnesses (e.g., to behave like other residents in village gatherings), but they do not necessarily intend to impose anything on them. In a way, they behave respectfully with respect to the choices Erkin and his co-religionists have made. This group can be characterized as having a neutral attitude.

I also met several villagers who did not answer my questions about the Jehovah’s Witnesses, briefly stating that they had nothing to say about them or saying that they did not know whether any Jehovah’s Witnesses lived in Abdraimov. But there were some who were completely opposed to the presence of Jehovah’s Witnesses in the village.

I met a man, aged about 60, who lives near the Kingdom Hall. His stance on the Jehovah’s Witnesses is somewhat ambiguous. On the one hand, he says the Witnesses mainly attract the youth, and thus parents in the village are worried about their children’s proper upbringing according to local customs and traditions. They believe that if their children convert to the Jehovah’s Witnesses, that will damage the relationship between generations. On the other hand, this interviewee says he would not mind if the Witnesses built their Kingdom Hall on the outskirts of Abdraimov:

It would be better for them to build it not in the middle of the village, but outside of it. They used to gather on the outskirts before; I have no idea how they came here. The conflict will recur one day. Back then, the young men almost destroyed the place, but if they did, they would be brought to justice before the law. They might do it since they are young. […] No one would care if they had it [Kingdom Hall] somewhere outside the village, especially since they have documents and the laws allow them to work.

Besides that, one of the most widespread arguments among the villagers I encountered is as follows: “I know the Kyrgyz Republic is a secular country, everyone has a right to choose a faith, but we are Muslims and it does not comply with our faith to convert to another faith.” Despite their negative attitude toward the Witnesses, however, such villagers do not necessarily intend to re-convert Erkin and his co-religionists back to Islam. However, they are ready to support and join protests against the Jehovah’s Witnesses when they happen.

The 2019 protests were apparently initiated by a man aged about 40 who lives not far from the Kingdom Hall. He was the bearded man of whom Erkin spoke. When we met, he first asked if I was a Muslim before proceeding with the conversation. The risk was that—depending on my answer—the tone of the conversation could shift. I encountered a similar situation with the village imam, who had also participated in the protest. I told both of them I was a Muslim, and in one case I was even asked to pronounce the shahada.[15] Many residents were mainly concerned why on earth I, as a Muslim, was interested in studying the community they despise, and they asked whether I was being paid by the Witnesses to investigate the issue.

The man who organized the protest declared that the villagers’ issue with the Jehovah’s Witnesses is not new and that the protest last year was a result of “long-piled-up problems.” He had been “warning” Erkin to stop preaching his religion around because “it was a foreign religion for the village.” He explains:

Before the protest, we warned Erkin many times that it was not proper and to stop it. He told me that everything he did complies with the law. However, people here seem not to care about the law. Here, the people are the law, aren’t they? If there are no people, then whom [are] the laws for? Then the people who live in our neighborhood gathered and put forward a demand: “They [Jehovah’s Witnesses] should not live here. Practice it where it originated as you wish. Go there where it is present. Do not spread it where it does not exist.” If you want to preach, become a Muslim and go ahead [preaching Islam]. […] Although they have permission, the people, neighbors do not want them. […] As Muslims we did not want them.

His arguments are based mainly on religion (Islam), which he uses to justify his actions, whereas other villagers rely more on Kyrgyz laws or local traditions. This interviewee characterizes Erkin and other Witnesses as deviants, and he sees only two options: either Erkin comes back to Islam or he leaves the village (and probably the country). I met several villagers like him who strongly believe that Erkin and others like him should be re-converted back to Islam because it is not acceptable to deviate: “They have gone astray and deviated. If only Allah were to give them guidance, it would be good for them. […] It is not permissible for Muslims to leave their faith. It is written in the Quran; they are regarded as deviants.” He went on to say:

[On our street] there are some alcoholics who have become slaves to alcohol. The other [Erkin] is the person who really pursues going to Heaven, but he is lost. As for the alcoholics, fundamentally they are Muslims—even after they quit drinking, they remain Muslims. As for others, they are harming their relatives and Islam by converting to become Jehovah’s Witnesses. If you are a Muslim, you should know and understand it better.He asked me: “Some say that a long time ago when Erkin and his family faced difficulties, they were paid money to convert to the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Would you like them to live here? Do you mind this religion or not?” He thus shared one of the most widespread rumors in the village about the Witnesses: Erkin and other converts have sold their religion and received money for being Witnesses. However, Erkin makes his living by renting out his field, cooking pastries, or sometimes working as a driver and a plumber in the village. “If I received money from the Witnesses, why would I do several jobs? People seem to say anything, but apparently I cannot change their minds,” Erkin says.

Since the conflict occurred last year, no one has come to him and expressed a negative attitude. Yet from time to time, he receives a scornful look from his fellow residents and overhears unpleasant words about his community like “they are Baptists, they are not Muslims. When they congregate, they turn off the light and do bad things, they get money.” Erkin commented:

I understand them, they receive inaccurate information about us. I usually invite them to see. I tell them it is not true. Some people, after attending the congregation, say it seems great, there is apparently no bad thing in it. Some people, out of fear [of the rest of the population], do not talk and get in touch with us. It would be good if people treated us with understanding. Unfortunately, nobody can mainstream human opinion, unless God does. We will continue to live. People will gossip behind our backs. People will confront us. There will be obstacles. Such things will happen and will not stop. The most important thing is that we are complying with God’s Word in the Holy Book. It was said this good news has to be spread. If we do not spread it here, who will?

In a village where many oppose the Witnesses, it would seem almost impossible to find a villager with a positive attitude. But an elderly man I met with the help of Erkin was one exception. The elderly man considers himself almost a Jehovah’s Witness, but has apparently not been recognized as such by the community, since I was able to meet with him without restrictions. He first encountered the Witnesses and their teachings six years ago. He used to read the Bible and actively kept in touch with the Witnesses. In 2017, his eyesight started to fail, and ever since, he has been mainly reading the Bible. Currently, he is studying the Bible with Erkin. His wife passed away a few years ago. Now he lives with his youngest son’s family. His family is aware of his faith, but he usually keeps it inside and does not want his neighbors and others to find out. He tells me:

Before, I used to pray namaz [Islamic worship]; now I cannot worship like before. But I cannot get out of the crowd because I am a coward, to be honest. I could come out but I have sons, daughters, and grandchildren. They fear that the people will cause trouble for us. They support me reading the Holy Book and meeting with the Jehovah’s Witnesses. But it is difficult to do so openly, as everyone around here is Muslim, all elders here pray namaz. They do not know that I read the Holy Book. When they ask if I read namaz, I tell them I have no strength to do it five times, but my heart is with Jehovah. […] Mostly I hide my faith from the people because of my sons’ wish. If the people knew about my faith, they could not do anything. I am not afraid of them. But my children do not want to be singled out and want to live just like others. If I were younger, I would go out and do whatever I want. Since I rely on my children’s help, I listen to them.

From what I could observe, there was no meaningful exchange of ideas between the Witnesses and the other residents of Abdraimov. When I asked those with mainly negative attitudes whether they had made an attempt to clarify some of their assumptions about the Jehovah’s Witnesses, they replied that they had no desire to do so.

Apart from the misunderstandings of his co-villagers, Erkin considers that his right to freedom of belief is protected in Abdraimov. However, such actions as the village protest against the construction of a place of worship or property damage cannot simply be reduced to misunderstandings. Erkin adds:

Freedom of religion is protected and we can live and preach here. We hold on to our congregations. If it was not protected, we would have been expelled from the village already. No one is persecuting us here. It would, however, be good if people treated us with understanding.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This paper has explored the issue of freedom of belief of minority religions in Kyrgyzstan through the case study of the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Abdraimov village of Bazar-Korgon District. It showed that members of minority religions experience ostracization and discrimination from society as well as the local authorities. There have been cases when the rights of members of minority religions—though they are full citizens—have been explicitly or implicitly restricted on multiple levels.

Analysis revealed that such actions usually result from a low level of knowledge of minority religions among the general public. To eradicate the violations of freedom of belief and conflicts on religious grounds, the State Commission for Religious Affairs (SCRA) and other state institutions will have to work on improving citizens’ religious literacy. This can be achieved by introducing classes on different religions to secondary schools and organizing awareness campaigns across the country, among other actions.

The introduction of classes in secondary schools and the promotion of religious awareness among citizens will also help to develop and promote the adoption of a serious religious terminology, which is severely lacking in Kyrgyzstan. This will be particularly useful for journalists, who usually use biased and discriminatory vocabulary to report on religious minorities. On the receiving end, citizens should be provided with the opportunity to comprehend diverse religious environments to reduce prejudice and discrimination against minority religions in Kyrgyz society.

The SCRA should maintain close connections with religious organizations regardless of their size and promote cooperation among them. Regulations for integrating minority religions into interfaith dialogue, which is often limited to Sunni Islam and Christian Orthodoxy, should also be worked out. This cooperation will contribute to the acceptance and reinforcement of religious pluralism. In addition, the SCRA, the only state institution that oversees the country’s religious sphere, should increase its number of officers: it currently has just one officer per province, which limits the institution’s efficiency.

These measures may contribute to preventing conflicts on religious grounds. State institutions, particularly law enforcement agencies, should intervene in incidents of wrongdoing on religious grounds and punish offenders under the law so that discrimination and oppression in any form will decline. In part, these problems have been caused by a lack of strong state institutions, an issue with which Kyrgyzstan has been grappling for its nearly 30 years of independence.

[1] GSoD Indices include data on main democracy attributes such as Representative Government, Checks on Government, Impartial Administration, Participatory Engagement, and Fundamental Rights (with freedom of religion falling into the last category). The GSoD offers data for 163 countries for the period of 1975–2019. The scoring goes from 0 to 1: a score of 0.00–0.399 means low achievement, 0.40–0.70 is mid-range, and 0.701–1.00 indicates high performance. The freedom of religion component includes subcomponents such as religious organization repression and freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

[2] Mathijs Pelkmans, Religious Repression and Religious Freedom: An Analysis of Their Contradictions in (Post-) Soviet Contexts, in Politics of Religious Freedom, ed. Winnifred Fallers Sullivan, Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, Saba Mahmood, and Peter G. Danchin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 313–323.

[3] Emil Nasritdinov and Elmira Esenamanova, “Religioznaia bezopasnost’ v Kyrgyzskoi Respublike,” 2014, Bishkek, https://carnegieendowment.org/2014/06/26/ru-pub-56026

[4] Kanatbek Murzahalilov, “Din menen myizamdyn kyldan ichke chegi,” Azattyk.org, June 26, 2020, https://www.azattyk.org/a/kyrgyzstan-din-erkindik-2020/30685996.html, accessed January 19, 2021.

[5] Mushfig Bayram, “KYRGYZSTAN: Impunity for Body Snatching Officials,” Forum 18, March 22, 2017, https://www.forum18.org/archive.php?article_id=2266, accessed January 19, 2021.

[6] Mushfig Bayram, “KYRGYZSTAN: Church Arson Follows Long-Standing Government Failures,” Forum 18, January 24, 2018, https://www.forum18.org/archive.php?article_id=2346, accessed January 19, 2021.

[7] JW.org, “Kyrgyzstan Overview,” https://www.jw.org/en/news/legal/by-region/kyrgyzstan/jehovah-witness-facts/, accessed January 19, 2021.

[8] For example, in 2010, the list of 200 Witnesses was denied approval by the district council in Kadamjay without any reasons being given. In 2011, the Witnesses’ second attempt to get the list approved was likewise unsuccessful. But this time, the district council revealed the reason for refusal: “… As the Kadamjay area was on the border with Uzbekistan, it was highly prone to religious conflict, and … as the population of the region confessed a single religion, and in order to protect the stability of the area and peace among its residents, the previous decision not to approve the list of members of the constituent council of the Religious Organization should not be changed.” The Witnesses in turn found this statement discriminatory. They provided two arguments. First, there are already citizens who are Jehovah’s Witnesses and reside in the area. Second, there were no cases of the Witnesses interrupting stability and peace among the local people.

[9] Alymbek Bekmanov, personal interview with the author, September 2020.

[10] For instance, in Naryn and Osh, several trials were held one after another. In 2014, when a Jehovah’s Witness resident of Naryn preached to her neighbor, she was detained and accused of propagating the faith of a religious organization that was not registered in Naryn (JW.org, “Religious Freedom at a Crossroads in Kyrgyzstan,” March 2, 2015, https://www.jw.org/en/news/legal/by-region/kyrgyzstan/religious-freedom-cases/, accessed January 19, 2021). In another case, in 2015 in Osh, the Witnesses were physically attacked and detained by law enforcement when they congregated in a rented café. This incident was also explained by the lack of a registration; thus, the congregation was deemed illegal (JW.org, “Will Victims of Police Brutality in Osh Receive Justice?” March 1, 2016, https://www.jw.org/en/news/legal/by-region/kyrgyzstan/osh-police-brutality/, accessed January 19, 2021). In both cases (in Naryn and Osh), the court found in favor of the Witnesses, with judges relying on the decision of the Constitutional Court.

[11] The UN Human Rights Committee examined the Witnesses’ case in 2019: Human Rights Committee, “Views Adopted by the Committee under Article 5 (4) of the Optional Protocol, Concerning Communication No. 2312/2013,” May 27, 2019, http://undocs.org/CCPR/C/125/D/2312/2013, accessed January 21, 2021 (after opening choose preferred language).

[12] Anthony Gill, The Political Origins of Religious Liberty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

[13] Alymbek Bekmanov, personal interview with the author, September 2020.

[14] Officially, it is still a village; the officials are currently in the process of turning it into a town.

[15] Islamic testimony of faith usually used in Arabic: “There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah.”

Funding: This research was supported by the Fellowship Program of Soros Kyrgyzstan Foundation.