Hélène Thibault has been Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Nazarbayev University, Kazakhstan, since 2016. She specializes in ethnography, gender, and the securitization of Islam in Central Asia. She is the author of Transforming Tajikistan: Nation-Building and Islam in Central Asia (2017) and has been published in Central Asian Survey, Ethnic and Racial Studies, and the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, among others. Her current projects look at gender issues, including marriage, polygyny, and male sex-work.

As a soft authoritarian state whose society is considered relatively socially conservative, Kazakhstan’s regulation of sexual practices and marriage blends liberal lifestyles with patriarchal outlooks. The issue of polygyny has been well researched in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, often in light of women’s economic vulnerability, the re-traditionalization of gender roles, and increasing religiosity. In contrast, this paper highlights the cosmopolitan, sometimes glamourous, character of polygyny in oil-rich Kazakhstan. In Kazakhstan, many associate polygyny with women’s economic vulnerability and opportunism, others with the country’s perceived demographic problems, and still others with religious traditions and patriarchal oppression. However, interviews and focus groups I conducted in 2019-2020 reveal that becoming a second wife (locally referred to as tokal) represents a way for some women to retain independence in their relationships.

The Legal Status of Polygyny

In contrast to other Central Asian countries, polygyny is not a crime in Kazakhstan. Its legal status is equivocal because while the law on marriage forbids it, the criminal codex makes no mention of polygyny. Kazakhstan’s criminal codex was modified in January 1998, at which time the article concerning “bigamy or polygamy,” which had been present since 1959, was removed.[2] However, Article 11 of Section 2 of the Law on Marriage and Family notes that the state cannot register a marriage (known as ZAGS) if one of the individuals is already officially married.[3] Other than this provision about the impossibility of registering a second marriage, nothing in the law specifically condemns or criminalizes men or women who sustain long-term relationships and family relations with more than one partner. Therefore, no one can be prosecuted for having more than one wife or partner.

The Kazakhstani government has attempted to do more to normalize polygyny. In 2001, member of Parliament Amangeldy Aytaly initiated an amendment to the law on family and marriage that would have fully legalized polygyny, but the initiative was rejected. A second attempt in 2008 also failed.[4]

This legal ambiguity allows the institution of polygyny to flourish. Given its unlawful character, there are no reliable statistics on the extent of the phenomenon in Kazakhstan, but it is estimated that polygyny concerns 2% of Kazakhstani families.[5] Indeed, in 2013, a senior cleric at Almaty’s largest mosque declared that around 10% of all nikeh (Islamic marriage) ceremonies conducted in the mosque involved tokals.[6]

The Demography Argument

Some see polygyny as a solution to what they consider Kazakhstan’s demographic crisis. Kazakhstan has had sustained demographic growth since the mid-2000s, oscillating between 1.10% and 1.60%.[7] However, according to the late demographer Makash Tatimov, there were 850,000 more women of marriageable age than men in 2014.[8] Official statistics from 2014 likewise reveal a small but significant demographic imbalance between men and women, showing that women comprise 51.72% of Kazakh society and men 48.27%. This gap is more acute in urban areas, as reflected in the demography of Nur-Sultan, which has 421,277 women and 393,158 men.[9] Therefore, some argue that the legalization or normalization of polygyny could solve the country’s perceived demographic problem even if the population is growing.[10]

Demography appears to be a concern for a number of politicians, who politicize this issue as part of a broader nationalist agenda. Amantay Asilbek, an eccentric politician who has run for president on several occasions, has declared that: “In Kazakhstan, there are a lot of single women, and it is a national tragedy, because we lose potential mothers. I think polygamy would solve this problem.”[11] Zhumatay Aliyev, a member of Parliament, expressed similar concerns when asked to give his opinion on polygyny: “There are about a million young unmarried girls in Kazakhstan now! Perhaps that’s why I do not blame men who take a second wife. I’m glad for the improvement of demography and that there are fewer single hearts.”[12]

The demography argument is also reflected in popular narratives. In a short documentary produced by Russia Today in 2014, a Kazakh man who had two wives and sought more explicitly expressed a desire to contribute to population growth to “save his nation from extinction.” He indicated that he wished to have 30 to 40 children, a number impossible to reach with only one wife.[13]

Is Polygyny a Religious Issue?

The increase in polygyny is occurring in a context of limited Islamic revival that might legitimize the practice.[14] Among the 18 focus groups I conducted in three different cities of Kazakhstan (Almaty, Nur-Sultan and Kyzylorda), a majority of the 66 participants associated polygyny with Islam and saw its potential legalization as an undesirable violation of the separation of religion and state. However, people who engage in polygynous unions are not necessarily religious,[15] even if they use the Islamic argument to justify their decision to take a second wife.[16] Among the 16 polygynists I interviewed in different parts of Kazakhstan, only one identified as a practicing Muslim. Others self-identified as Muslims but did not respect many of the religious traditions; for instance, they did not recite prayers and did drink alcohol. The results of the survey I commissioned in 2019 also show very low support for polygyny, even among Kazakhstani Muslims. The table shows that more men than women approve the legalization of polygamy among all religions.

Table 1. Support for the legalization of polygyny

Should polygamy be legalized in Kazakhstan in order to provide some legal rights to second wives and to children born in these marriages?

| Islam | Christianity | Other religion | Non-religious person | ||

| Strongly Disagree | Women | 18% | 15% | 0% | 17% |

| Men | 14% | 17% | 33% | 18% | |

| Disagree | Women | 46% | 43% | 0% | 44% |

| Men | 33% | 35% | 17% | 35% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | Women | 13% | 20% | 0% | 19% |

| Men | 14% | 23% | 17% | 17% | |

| Agree | Women | 19% | 21% | 0% | 15% |

| Men | 32% | 21% | 33% | 27% | |

| Strongly agree | Women | 4% | 1% | 0% | 4% |

| Men | 6% | 4% | 4% | 2% |

Source: NAC Analytica 2019. N = 3025.

In order to protect women who are only married according to nikeh, the government toyed with the idea of forcing imams to require a state marriage certificate (ZAGS) before celebrating nikeh. This idea was dropped; only the obligation to perform the religious ceremony within the vicinity of a mosque was adopted.[17] Interestingly, the official clergy of Kazakhstan, the Spiritual Directorate of Muslims of Kazakhstan (known by its Russian acronym ДУМК or DUMK; also called the Mutfiyat), takes a favorable view of polygyny. Newlyweds who perform nikeh in Nur-Sultan’s mosques often receive a book called The Muslim Family, published in Kazakh by DUMK in 2017.[18] This book provides couples with guidelines for married life and raising children according to Islamic principles.

The book’s final section, entitled “Polygyny in Islam,” explains which passages of the Quran endorse and justify polygynous marriages and provides guidelines for contracting halal polygynous marriages. Another e-book found on the DUMK website[19] explains the rules regulating marriage according to the Hanafi school of jurisprudence. The reasons evoked to justify polygyny are multiple: to take care of orphans and widows, as well as to satisfy men’s sexual needs. Indeed, the book advises men and women to consider polygyny if the marriage has “grown cold.”[20] The Kazakh official clergy does not openly call for the legalization of polygyny but reckons that it would facilitate their work.[21] Yet my research shows that polygyny is not necessarily connected to religiosity.

Polygyny as a New Form of Companionship

Even if some consider that polygyny is a patriarchal institution that is unfavorable to women,[22] we must also explore the idea that becoming a second wife represents a way for Kazakhstani women to escape the traditional obligations of marriage.[23] In Kazakhstan, many households continue to be multigenerational; kelins (brides) are expected to take care of their in-laws and power relations can be quite unfavorable.[24] An interview given by one tokal in which she revealed that she had no desire to play the role of a traditional wife who is only there to serve her husband in exchange for material comfort and contended that she was “much happier to be a mistress than a quiet wife”[25] generated huge buzz online. Thus, even if there is still stigma associated with being a second wife, some Kazakhstani women may wish to become tokals in order to avoid a life they envision as limiting and unexciting.

My interviews with second wives bear this out. Three of the four second wives I interviewed were divorced professionals in their thirties with children from their first marriage. Contrary to the cliché of rich older men dating younger sexy women,[26] these women were only about 3-4 years younger than their partner; one was even the same age. Those three women had fairly similar stories: they were divorced, met someone by accident, and eventually fell in love. Even though they were initially unsure that they wanted to pursue a relationship with a married man, they carried on because of sentimental compatibility. When I asked them if they would rather have a full-time relationship and be their respective partners’ primary wives, their answers were unexpected. An interviewee from Taras replied:

I’m an egoist. My work is very difficult, I have lots of responsibilities and I want some time alone at night after work. I really respect personal space, mine and that of others. My husband wonders why I don’t text him all day. First, I’m busy, and second, people should feel free. A wife should not bother her husband all day. I’m very independent.[27]

She refused to live with her husband’s conservative parents because she did not want to become their uborshchitsa (cleaner). Her partner eventually married another, younger woman to take care of the parents; he now has two families. A second wife in her late thirties from Nur-Sultan who described herself as a workaholic indicated that she had no desire to live with her partner because she was too independent: “My first marriage proved that I am very impatient. I’m happy when my partner comes around but also happy when he leaves!”[28] The third interviewee, also from Nur-Sultan, mentioned that she felt very much loved and that she and her husband managed to maintain a good relationship because they made the most of their limited time together.

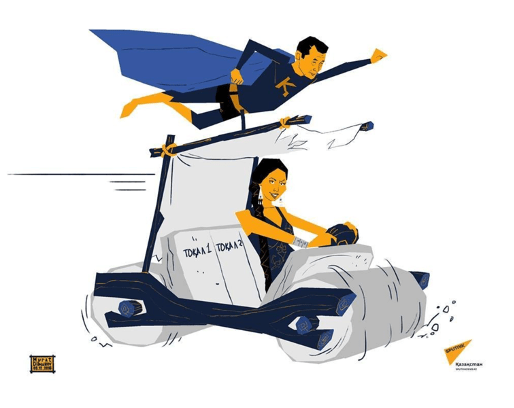

Cartoon representing a tokal supporting her husband

Another important aspect to consider is their economic situation. With the exception of one young second wife who married a much older man who was very wealthy, my other three female respondents all described themselves and their partners as middle-class. They had jobs, their own apartments, and financial independence, though they mentioned that their partner was still helping them financially, especially since they had children together. One man I interviewed in Nur-Sultan who had two wives mentioned that his second wife was a businesswoman and actually wealthier than him. Laughing, he declared: “She drives a Mercedes and I drive a Toyota; she is the one supporting me!” Yet economic vulnerability should not be ruled out. Zhanar Zhandosova, director of the Sange Research Center in Astana, declared in an interview: “Fewer Kazakh girls would become tokals if there were more normal opportunities for advancement. For too many of them, the only option is to gain access to a man’s finances.”[30]

Interviews with the directors of two dating agencies in Nur-Sultan also revealed the demand for such relationships. Both mentioned that many women who used their services would agree to be matched with men who were already married “if they are rich.”[31] One claimed to have formed 25 polygynous couples in 13 years of practice.[32] The other had included a special “tokal service” on her list of services in the past. However, she claimed that she had not been very successful at forming durable relationships because the interested parties could rarely find common ground. Whereas men usually had great hopes of finding romantic love, women were more interested in the material benefits associated with the relationship. Specifically, both agency directors mentioned that women wanted to enjoy their independence and often demanded their own apartment. The director of the agency that had once advertised tokal services indicated that she had stopped offering this service because she did not enjoy dealing with such people, especially since the relationships were rarely successful.[33]

These cases reveal that women are not simply the victims of an oppressive financial situation, but often retain some agency and are keen to negotiate the terms of relationships. It is not my intention, however, to deny the distress behind some of those relationships. Indeed, feelings of helplessness can inform one’s choice to become a second wife. One of my interviewees was a young woman living in Almaty who had not become a second wife but toyed with the idea when an older, rich, influential man proposed to her. She explained that she had met this man by chance in a store and they had started chatting. This happened at a moment when she felt very vulnerable: her family was struggling financially due to her father’s illness, which in turn was negatively affecting her performance at the university. She said this man was a reassuring figure and his attention and money helped her through those difficult times. Both being quite religious, they were never physically intimate. She eventually refused his proposal and moved on.[34]

My 21-year-old interviewee from Nur-Sultan became the second wife of a very wealthy businessman in his fifties. They met by chance at a work event and started a relationship. He helped her open a small store to allow her to support herself financially and bought her an apartment where she lived with her mother and newborn son. However, the relationship ended tragically when this man took his own life, for which she felt responsible. This young respondent explained that she had seen this man as a paternal, reassuring figure, something that was especially appealing given that she had grown up with an abusive, distant father.[35] These two narratives draw a complex, nuanced portrait of polygynous relationships as being driven not only by potential financial gains, but also by a quest for support and love.

The Normalization of Polygyny?

In a recent series of TV interviews about his life and legacy, First President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev was asked about his relations with women and casually described what dynamics with the first, second, and third wife should look like.[36] He spoke in general terms and did not specifically refer to his personal experience, but the remarks were intriguing in light of persistent rumours that Nazarbayev has multiple wives.[37] His statement is yet another indication that polygyny has become a recurrent, relatively banal theme in Kazakhstan.

A motion picture from 2016 portraying the issue of tokals

Even if it appears to be quite common, polygyny’s social acceptability is uncertain and has led to intense debates within Kazakhstani society because of its association with religion and the perceived violation of the secular nature of the state. However, beyond legalization, it’s the very idea of multiple companionship that is perceived negatively. As shown in Table 2, it is deemed unacceptable by a majority of people for non-Muslim men to have a second wife. Once again, the results are fairly similar among Muslims and people of other religious confessions.

Table 2. Support for polygyny for non-Muslims

It is acceptable for a non-Muslim man to take a second wife.

| Muslims | Christians | Other religion | Non-religious person | |

| Strongly Disagree | 10% | 12% | 17% | 11% |

| Disagree | 47% | 46% | 33% | 45% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 22% | 27% | 17% | 26% |

| Agree | 19% | 13% | 33% | 17% |

| Strongly agree | 2% | 1% | 0% | 1% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Source: NAC Analytica 2019. N = 3025.

Debates around the legalization of polygyny might open up a whole new chapter that would further challenge the dominant understanding of marriage as a monogamous heterosexual relationship: the legalization or normalization of polyandrous marriages. In the midst of the discussions about the legalization of polygyny in 2008, Bakhyt Syzdykova, a young female member of Parliament, commented: “If you want to legalize polygyny, then you also have to legalize polyandrous marriages—women having multiple husbands simultaneously—to give equal rights to men and women.”[39]

This is rather unlikely given that unlike polygyny, polyandry is not backed by local religious tradition and cultural practices. The Muslim clergy is unsurprisingly staunchly opposed to polyandrous marriage, arguing that it would make it impossible to determine paternity in cases where a woman has multiple husbands.[40] Beyond the religious issue, local standards of hegemonic masculinity and femininity, which valorize bold behaviors for men and chaste attitudes in women, are likely to prevail. Overall, the government certainly has an incentive to maintain the legal status quo. Yet given that gender values and attitudes are changing rapidly in Kazakhstan, we might see new forms of informal matrimony emerge in the future.

[1] Gulnaz Abduvali, “Sem’ samykh znamenitykh tokal Kazakhstana” [Kazakhstan’s Seven Most Famous Tokals], Nur KZ, September 30, 2016, https://kazakbol.com/sem-samyih-znamenityih-tokal-kazahstana-foto/.

[2] “Uzakonit’ mnogozhenstvo v Kazakhstane predlagaiut deputaty” [In Kazakhstan, Deputies Propose to Legalize Polygyny],” Zona, April 1, 2019, https://zonakz.net/2019/04/01/uzakonit-mnogozhenstvo-v-kazaxstane-predlagayut-deputaty/.

[3] “Kodeks Respubliki Kazakhstan ot 26 dekabria 2011 goda № 518-IV ‘O brake (supruzhestve) i sem’e’ (s izmeneniiami i dopolneniiami po sostoianiiu na 02.01.2021 g.) [Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan Dated December 26, 2011 No. 518-IV “On Marriage (Matrimony) and the Family” (with Amendments and Additions as of 01/02/2021)], https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=31102748, accessed March 8, 2021.

[4] Kazis Toguzbayev, “Mnogozhenstvo i kalym otmeneny. Da zdravstvuiut tokalki i kalym?” [Polygamy and Brideprice Modified. Long Live Tokalki and Brideprice?], Information System Paragraph, 2011, https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=31002077, accessed March 8, 2021.

[5] Askhat Akhmetbekov, “Demograf Makash Tatimov: mnogozhenstvo – stepnoe pravo Kazakhov” (Demographer Makash Tatimov: Polygyny—The Steppe’s Law of the Kazakhs), Zakon, October 29, 2014, https://www.zakon.kz/4656289-demograf-makash-tatimov-mnogozhenstvo.html, accessed March 8, 2021.

[6] Nariman Gizitdinov, “Rich Kazakhs Revive Polygamy as Women Seek Poverty Escape,” Bloomberg, December 3, 2013, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-12-02/rich-kazakhs-revive-polygamy-as-young-women-seek-poverty-escape.

[7] “Kazakhstan Population 2021 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs),” World Population Review, https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/kazakhstan-population, accessed March 8, 2021.

[8] Akhmetbekov, “Demograf Makash Tatimov.”

[9] “Kazakhstan Population 2021 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs),” World Population Review, https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/kazakhstan-population, accessed March 8, 2021.

[10] A.U Tanalinova, “K voprosu ob institute poligamii v Kazakhstane” [On the Question of the Institution of Polygamy in Kazakhstan], Vestnik KazNU. Seriia Iuridicheskaia 52, no. 4 (2009): 92–95. Interestingly, polygamy proves to have no particular effect on demographic growth. Women who marry men who have multiple partners are likely to have less children than if they were in monogamous relationships (Jacob A. Moorad, Daniel E. L. Promislow, Ken R. Smith, and Michael J. Wade, “Mating System Change Reduces the Strength of Sexual Selection in an American Frontier Population of the 19th Century,” Evolution and Human Behavior 32, no. 2 (2011): 147-55.

[11] Richard Orange, “Presidential Candidate Vows to Find Husbands for Kazakhstan’s Single Women,” The Telegraph, February 18, 2011, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/kazakhstan/8333350/Presidential-candidate-vows-to-find-husbands-for-Kazakhstans-single-women.html.

[12] “Deputat Aliyev vystupaet za mnogozhenstvo” [Deputy Aliyev Supports Polygyny], Total, December 23, 2013, https://total.kz/ru/news/obshchestvo/deputat_aliev_vystupaet_za_mnogo.

[13] “Tokal: Kazakh Women Who Seek to Become Second Wives,” YouTube video, 25:54, posted by “RT Documentary,” June 26, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PX_stzHgKxg, accessed March 8, 2021.

[14] G. M. Yemelianova, “Islam, National Identity and Politics in Contemporary Kazakhstan,” Asian Ethnicity 15, no. 3 (2014): 286–301, https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2013.847643.

[15] Rabiga Dyusengulova, “Kazakhstanskie tokalki rasskazali, kak ispol’zuiut svoikh sostoiatel’nykh ‘papikov'” [Kazakh Tokals Tell How They Use Their Wealthy “Daddies”), Newtimes, August 22, 2016, https://newtimes.kz/eksklyuziv/36906-kazakhstanskie-tokalki-rasskazali-kak-ispolzuyut-svoikh-sostoyatelnykh-papikov.

[16] Batyrbek Imangaliev, ‘“Religiia dlia nykh sluzhit prikrytiem’: tiurkolog rasskazala, pochemu kazakhstantsy prodolzhaiut brat’ tokal i otkuda eto prishlo” (“Religion Serves as a Cover for Them”: A Turkologist on Why Kazakhstanis Continue to Take Tokals and Where It Came From),” June 18, 2020, https://www.caravan.kz/news/religiya-dlya-nikh-sluzhit-prikrytiem-tyurkolog-rasskazala-pochemu-kazakhstancy-prodolzhayut-brat-tokal-i-otkuda-ehto-prishlo-647347/.

[17] Besides trying to regulate second marriages, the measure was also intended to tackle underage marriage among girls. It is believed that around 5% of Kazakh girls between 15 and 18 are married. Since underage marriage is officially forbidden, it can only be contracted by nikeh.

[18] DUMK, Islam Zhanuyasy [The Muslim Family] (Almaty: DUMK (Spiritual Directorate of Muslims of Kazakhstan, 2017).

[19] “Za religioznyi obriad brakosochetaniia bez ofitsial’noi registratsii braka nakazyvat’ ne budut” [Religious Marriage Ceremonies without Official Registration of Marriage Will Not Be Punished], Inform Buro, October 27, 2017, https://informburo.kz/novosti/ministr-po-delam-religiy-rk-otvetil-o-zaprete-nikyah-bez-oficialnoy-registracii-braka-.html.

[20] This e-book is not properly paginated. This reference appears on p. 72 of the pdf document.

[21] Interview with the Head of the Sharia & Fatwa department at DUMK, December 12, 2020.

[22] Akhmetbekov, “Demograf Makash Tatimov.”

[23] This is an argument that I have explored in a previous article about Tajikistan. Hélène Thibault (2018) Labour migration, sex, and polygyny: negotiating patriarchy in Tajikistan, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41:15, 2809-2826, DOI

[24] Diana T. Kudaibergenova, ‘Project ‘Kelin’: Marriage, Women and Re-Traditionalization in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan,” in Women of Asia: Globalization, Development, and Social Change, ed. Mehrangiz Najafizadeh and Linda Lindsay (New York: Routledge, 2018), 379–90.

[25] Aldiyar Kosenov, “Priznaniia Almatinskoi tokal obsuzhdayit pol’zovateli seti” [Confessions of an Almaty Tokal are Discussed by Internet Users], Tengri News, July 13, 2016, https://tengrinews.kz/story/priznaniya-almatinskoy-tokal-obsujdayut-polzovateli-seti-298503/.

[26] Abduvali, “Sem’ samykh znamenitykh tokal Kazakhstana.”

[27] Telephone interview, January 19, 2020, Taraz.

[28] Face-to-face interview, November 1, 2020, Nur-Sultan.

[29] “Tokal vo imia rodiny,” Sputnik, December 9, 2016, https://ru.sputnik.kz/caricature/20161209/1182403/tokal-vo-imya-rodiny.html, accessed March 8, 2021.

[30] Gizitdinov, “Rich Kazakhs Revive Polygamy as Women Seek Poverty Escape.”

[31] Interview with Natalya Mikhailovna Tereshenko, director of the agency “Ia i ty” (Me and You), Nur-Sultan, April 5, 2019.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Interview with the director of a dating agency, Astana, April 8, 2019. The respondent preferred not to be named.

[34] Telephone interview, Almaty, January 20, 2020.

[35] Face-to-face interview, Nur-Sultan, January 19, 2020.

[36] “Nazarbayeva sprosili ob otnosheniiakh s zhenshchinami” [Nazarbayev Was Asked about Relationships with Women], Tengri News, January 8, 2021, https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/nazarbaeva-sprosili-ob-otnosheniyah-s-jenschinami-425366/.

[37] Kazis Toguzbaev, “‘Strane vriad li nuzhno znat’’? Zakrytost’ lichnoy zhizni pravitelei” (“Does the Country Need to know”? The Closed Personal Life of Rulers), Radio Azattyk, October 22, 2019, https://rus.azattyq.org/a/kazakhstan-information-private-life-of-politicians/30229129.html.

[38] See “My Husband’s Wife Movie,” http://www.myhusbandswifemovie.com/, accessed April 13, 2021.

[39] Farangis Najibullah, “Polygamy: A Fact of Life In Kazakhstan,” Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, June 21, 2011, https://www.rferl.org/a/polygamy_a_fact_of_life_in_kazakhstan/24242198.html.

[40] Interview with the Head of the Sharia & Fatwa department at DUMK, December 12, 2020.