By Julien Bruley and Iliias Mamadiiarov

Julien Bruley holds a PhD in social anthropology from the University of Lille (Clerse/Sesam). His doctoral dissertation focused on the Kyrgyz epic of Manas and its recent evolutions on the edge of politic, tradition and spectacle (2009-2019). He is now interested in studying the realm of Kyrgyz traditional and contemporary art and performance as a new space for public debate and a tool for criticism. He is also a regular collaborator to the online French-German newspaper Novastan. Some of his work can be found at https://univ-lille.academia.edu/JulienBruley.

Iliias Mamadiiarov is a PhD student at Europe-Eurasia Research Center (CREE), INALCO, Paris, France and a research associate at French Institute for Central Asian Studies (IFEAC), Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. The focus of Iliias’ research interests include the role of microfinance, trust, informal economy, economic anthropology and economic psychology in the community development projects in post-Soviet Central Asia. Previously, Iliias has worked as a scientific assistant at IFEAC (2016-2019) and the Head of International Office of American University of Central Asia (AUCA) (2013-2016).

The present article seeks to provide an overview of COVID-19 health crisis management in Kyrgyzstan at the macro and micro levels. As a matter of fact, Central Asia was hit relatively late by the pandemic. Indeed, the outbreak expanded in the region after it had affected China, the Russian Far East, and Europe. The first confirmed cases of COVID-19 appeared in the region in the second half of March: first in Uzbekistan, then in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and finally in Tajikistan in May 2020. As for Turkmenistan, it remains an exception since the country stated it has recorded zero official cases of coronavirus.

Likewise, as in many regions across the world, in Central Asia the pandemic served as a trigger event that produced exceptional political, social, economic, and cultural circumstances that required the implementation of various measures on the part of local governments in order to alleviate the consequences of the crisis. In this regard, Kyrgyzstan finds itself in a peculiar situation as the country’s dilapidated and vulnerable political and economic institutions have had to maintain a precarious balance both on the domestic and the international front. Furthermore, the pandemic has fully exposed vulnerabilities of this developing country, also highlighting its prompt reaction to the crisis.

The current study attempts to carry out two levels of analysis, macro and micro, to be placed in an evolutionary chronological perspective of the COVID-19 crisis in Kyrgyzstan. As such, the study puts an emphasis on the so-called anticipated “return to normal”—a period which offered a spurious end to the health crisis in the country some time at the end of May or beginning of June 2020. Finally, to reflect upon these developments as well as to elaborate on the potential implications of the present outbreak, this paper draws conclusions based on two main sources: data collected in the Kyrgyz media and data obtained during interviews with actors of Kyrgyz public life.

Kyrgyzstan: The period of the propagation of the pandemic

While its geographic proximity to China would suggest otherwise, according to official data, Central Asia was able to steer clear from contracting the virus during the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in the Chinese mainland. In its capacity as one of the key economic partners in Central Asia as well as an active participant of China’s Belt and Road project, Kyrgyzstan saw its first fears related to the possible spread of the virus on its territory set in towards the end of January 2020. The government adopted several measures in an attempt to the stave off the immediate epidemiological threat that included, among other things, the closures of land borders with its powerful neighbor along with the suspension of all flights to and from China.

As early as February, Manas International Airport, the country’s principal airport located in the northern part of Bishkek, introduced mandatory temperature control for passengers arriving on every international flight. The government took further proactive actions as it imposed restrictions on public gatherings. The chain of events evolved rapidly during the following weeks: in March, all the airlines flying to Kyrgyzstan cancelled their flights, and Russia altogether closed its borders to foreigners. In summary, the government put a high priority on measures aimed at obviating the necessity of countrywide lockdowns to prevent possible infections slipping in through land or air borders. But the results of such drastic measures were not long in coming. Indeed, in the face of complete closures of borders and suspension of airline traffic with neighboring countries such as Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and China, Kyrgyzstan quickly found itself in a state of de facto isolation.

As a matter of fact, a retrospective study of the COVID-19 pandemic in Kyrgyzstan allows us to hypothesize that, even if a government’s attempts to ward off the spread of the virus may not have been as impeccable as many outspoken Kyrgyz citizens wished they were, the measures nevertheless contributed in keeping the country virus-free for a certain period of time. In particular, it was only on March 18, 2020, that Kyrgyzstan registered its first confirmed COVID-19 cases. Three people from Suzak district, in the southern part of the country, who had earlier returned from pilgrimage to Mecca, were diagnosed with coronavirus after they visited a local hospital following their health complications.

With the further increase of COVID-19 cases that followed the introduction of quarantine measures on March 17, the government declared a countrywide state of emergency on March 25, with curfews introduced in the major cities in the south and in the capital Bishkek. Initially set to last from March 25 to April 15, the state of emergency was extended until May 10, following the decisions of Kyrgyzstan’s neighbors such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The quarantine measures halted almost all economic activity. With the exception of supermarkets and pharmacies, which remained open only during specified daytime hours, most other businesses had to wait until June 1 to become fully operational again. Finally, the infections gradually spread to the rest of Kyrgyzstan, with Talas oblast being one of the last to be affected upon the renewal of interregional transportation inside the country.

Kyrgyzstan during quarantine, first observations

Along with an obvious countrywide economic slowdown, the quarantine resulted in somewhat less discernible but nevertheless significant impacts on domestic and legal levels. This section provides a quick review of the repercussions stemming from the latter fields.

Domestic violence

According to Pomfret, apart from endemic corruption and pervasive clientelism, an “increasing Kyrgyz chauvinism” has been one of the marked evolutions that the country experienced since its independence. Furthermore, it appears that against the backdrop of strict confinement, the rising trend of male chauvinism has triggered an upsurge of incidents of domestic violence across the country.

Indeed, as Akisheva reports in her detailed analysis of cases of abuse against women during lockdown in Kyrgyzstan, if during the pre-pandemic period six in ten women were “beaten, sexually abused, or otherwise ill-treated,” within the context of quarantine, the country has recorded a 60% rise in the number of cases of domestic violence against women. In fact, with families restricted to living in clusters during lockdown, men have been forced to spend lengthier periods of time than usual at home with their spouses. The conditions have substantially raised the cases of abuse against women throughout the country, revealing the tensions and social divisions existing in Kyrgyz society.

A particularly manifest example of the latter is the incident that took place on March 8, when a parade, in support of women’s rights and composed predominantly of women, was disrupted by masked men belonging to conservative, nationalist-patriotic groups such as Kyrk-Choro.

Legal aspects

Numerous issues have surfaced with respect to repercussions in legal fields, such as families being deprived of the opportunity to visit their relatives in prison, and employees requiring legal support as they face massive lay-offs due to lockdown. Based on our anonymous interview with a private law firm in Bishkek, it was possible to shed light on certain developments that took place during the countrywide confinement period. As such, the law company observed a considerable rise, i.e., 30%, in the number of requests for legal consultation from employees who had been abruptly laid off during quarantine. The majority of the lay-offs, our interlocutor explained, concerned freelancers as well as individuals working in the garment sector—a group which is financially vulnerable and therefore treated as expendable due to the informal nature of the labor market, which explains the absence of employment agreements for this sector’s workers.

Another important evolution concerns the prisons. Restrictions to visit inmates impacted not only the family members of prisoners, but also a majority of doctors and lawyers, too. For instance, out of some 2,500 lawyers who applied for state authorization to access their clients in jails, only 139 received authorization during the lockdown. The number is to be compared with the pre-pandemic period when almost all of the lawyers requesting authorization to access jails received them.[1]

Major economic consequences of the initial lockdown

As with many developing countries vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks, in Kyrgyzstan the economic repercussions stemming from external or internal shocks tend to exert a major effect on the country’s political stability. Indeed, since gaining its independence, Kyrgyzstan has been profoundly shaken by two incidents of political distress, with the last one, as Pomfret explains, resulting from the Russian economic recession of 2008–2009. With a substantial fall of remittances coming from Kyrgyz migrant workers in Russia as well as the workers’ gradual return home, the country experienced a deep economic recession which eventually provoked a violent overthrow of the second Kyrgyz President, Kurmanbek Bakiyev, in 2010.

Certainly, the unprecedented nature of the present health crisis makes it extremely difficult to provide an all-encompassing analysis of the economic consequences of the pandemic. Nevertheless, it is possible to shed light on immediate macroeconomic impacts of the quarantine measures as well as to look upon several economic trajectories in which coronavirus can leave a lasting negative impact.

One of the foremost sectors in Kyrgyzstan hit hard by the health crisis was the financial market. In particular, the Kyrgyz som (KGS) experienced a number of major fluctuations in the days before and during the initial quarantine period. Indeed, a week before the announcement of the first official cases of COVID-19 in the country, the som’s exchange rate against the US dollar decreased by 4%. To prevent the panic buying of US dollars, the National Bank of Kyrgyz Republic (NBKR) performed a monetary intervention by selling US$53.7 million. However, despite the anticipated forecast of monetary stabilization, the Kyrgyz som continued to plummet, hitting the exchange rate of 85 som against $1 (to compare with 69 som per 1 of pre-pandemic period) on March 19. In his press conference, the director of the NBKR, Tolkunbek Abdygulov, underlined two factors to explain the drastic devaluation of national currency. On the one hand, he argued that the rising demand for dollars in the country was driven by psychological factors of buyers set against the backdrop of the global health crisis of COVID-19. On the other hand, the fall of international oil prices which affected internal financial markets was seen as the second reason causing monetary fluctuations.

Figure 1 provides an illustration of the fluctuations of the Kyrgyz som’s exchange rate in relation to the number of confirmed cases of coronavirus. To corroborate the explanations of the director of NBKR, we performed a bivariate analysis to examine the correlation between the pandemic and fluctuations of the Kyrgyz national currency. In particular, the application of a simple linear regression analysis taking the daily number of new infections as an independent variable and the exchange rate as a dependent variable results in an , i.e., the correlation coefficient, of 0.2835 approximately 0.3. Furthermore, with the application of a shorthand formula to test the statistical significance (), we obtain . In other words, at an approximate significance level of 0.05, it is possible to assert that a positive linear relationship between the spread of COVID-19 infections and fluctuations of the national currency exists and is statistically significant.

Source: 1. National Bank of Kyrgyz Republic, USD-KGS “Official Exchange Rate from March 11, 2020 to May 14, 2020”.

2. Official site on coronavirus in Kyrgyzstan.

An important caveat must be taken into account when looking at the bivariate analysis presented above. First, the simple linear correlation does not seek in any way to explain all the complexities of the financial markets in Kyrgyzstan (as well as in a global perspective) in relation to the COVID-19 crisis. Indeed, given the fact that financial markets have numerous coalescing factors which impact their course, their study requires analyses which go far beyond the bivariate regression analysis applied here. Second, the primary objective of our study was to corroborate the explanations put forward by the director of NBKR, who held the pandemic, among other things, to be responsible for fluctuations of national currency. Third, the analysis employed a fixed period, i.e., from March 11, the day of the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Kazakhstan that immediately impacted the price of dollars in the region, through to May 10, the day of the end of the state of emergency in Kyrgyzstan and the partial lifting of the confinement order. More importantly, though, NBKR’s efforts to prevent the devaluation of national currency paid off towards the end of May 2020 with relative stability of som’s exchange rate but at the cost of major monetary interventions.

Another significant economic aspect to examine within the present health crisis concerns the remittances of Kyrgyz migrant workers in Russian Federation. Indeed, since Kyrgyzstan is one of the world’s top countries dependent on foreign remittances, the pandemic takes a particularly heavy toll on the country’s economy. According to Suzy Blondin, the pandemic has produced a mobility problem for the tens of thousands of Kyrgyz households from mountainous regions of the country whose family members and other relatives work in Russia. With quarantine measures significantly hampering international travels, migrant workers face the risk of losing mobility—and subsequently jobs—driving more families into poverty. Indeed, according to the estimations of the World Bank, the COVID-19 crisis may trigger up to a 27% reduction of remittances to European and Central Asian countries due to a “fall in the wages and employment of migrant workers, who tend to be more vulnerable to loss of employment and wages during an economic crisis in a host country.” Along with the possible soaring unemployment levels and the rise in poverty, it seems that the health crisis has already triggered a much-feared recession for Kyrgyzstan’s remittance-dependent economy, as argued by Kyrgyz economist Nurgul Akimova.

In the same vein, the World Bank projects several outcomes of the present crisis in Kyrgyzstan. In the best-case scenario, with an inflation rate of 5% and a reduction in remittances of 30%, the crisis may drive some 400,000 individuals (roughly 5.9% of the population) below the poverty line. By contrast, the worst-case scenario, with an inflation rate of 20% and a reduction in remittances to 50%, may see up to 1.5 million people (approximately 22% of the population) facing the risk of falling below the poverty line.[2] It is important to note that the projection is based on the national poverty line in Kyrgyzstan (see Figure 2), which suggests that 22% of the population, or a little less than one fourth of the country’s residents, are already considered as poor during the pre-pandemic period. Hence, the fact that worst-case scenario of COVID-19 may plunge close to half of the country’s population, i.e., 44%, below the poverty line, provided that no appropriate intervention measures are put in place, sends an alarming signal for the necessity of implementing appropriate policies to alleviate the impact of the crisis.

Source: World Bank, DataBank, 2020.

The pandemic’s threat of driving 44% of the population below the poverty line implies that more than 15 years of the country’s fight against poverty is at risk. In this regard, such a distressing outcome is closely linked to the notion of “vulnerability to poverty,” a concept which pertains to households’ “resilience against a shock—the likelihood that a shock will result in a decline in well-being.” In Kyrgyzstan, the level of vulnerability stands at a significantly high level. More specifically, the declining level of national poverty in the country over the years was offset by a growing number of financially precarious households that managed to remain above the poverty line by a narrow margin. Figure 3 illustrates the extent of vulnerability to poverty in Kyrgyzstan. The graph shows that more than 60% of households remain in the vulnerability zone, which implies that economic recession threatens to take a heavy toll on more than half of the country’s population.

Source: 1. World Bank, DataBank, July, 2020.

2. World Bank. Kyrgyz Republic: From Vulnerability to Prosperity. A Systematic Country Diagnostic, 2018, 2018.

Last but not least, Kyrgyzstan will have to face a major challenge in the near future: the country’s foreign debt. It is certain that the present health crisis significantly hampers the country’s efforts at debt settlement. As of 2019, the foreign debt constituted 50% of Kyrgyz GPD, with China representing the chief creditor, i.e., more than 45%. Nonetheless, one reassuring aspect of the sum owed to China concerns the nature of the loans. In particular, almost all of the loans that Kyrgyzstan has contracted with the Chinese government are concessional. Therefore, as Bakyt Dubashov, the chief economist for Kyrgyzstan at the World Bank, argues, repayment terms of these loans are flexible. Finally, the fact that China has agreed to defer the repayment of Kyrgyz loans for the entirety of 2020 demonstrates, among other things, the flexible nature of the debt.

A crisis of trust?

« Savons-nous encore faire confiance ?» (Do We Still Know How to Trust?) is the title of the article, translated from German, published in a Swiss journal, Courrier International. Published on July 8, 2020, the article points out, among other things, that our society, once based on conviction, control, and confidence as the key elements of its stability, suffers today from a deep disarray marked by the omnipresent environment of uncertainty and fear due to the pandemic: “Before the pandemic, we lived in societies based on control, risk minimization and uncertainty reduction. And then crash! All our convictions were shaken.” While the article examines the general situation of individuals’ mistrust of scientific experts and local authorities generated by the spread of coronavirus, it should be noted that in Kyrgyzstan, distrust of public institutions existed long before the current health crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic further worsened the problem of mistrust, a development which comes against the backdrop of the enormous challenges that the country’s fragile health care system has been facing since the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Indeed, according to the study carried out by the National Statistics Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic in the second half of 2019 on trust levels, the country’s Ministry of Health held one of the lowest scores of trust of the population, appearing at the bottom of some 47 state institutions ranked in order of their trustworthiness. Furthermore, the survey of Bishkek residents evaluates the Ministry of Health as an agency with one of the highest levels of corruption (see Figure 4). With this caveat in mind, it is possible to assert that one of the reasons for the skyrocketing COVID-19 death cases, especially in Bishkek from the end of June 2020, may be related partly to the public’s lack of trust and unwillingness to heed the anti-COVID-19 public awareness campaign launched by the Ministry of Health. In particular, since the start of the lockdown, the Ministry of Health has repeatedly insisted on the importance of following social distancing rules as well as avoiding crowded places and events with mass gatherings. But the rising number of infections that shook the country in July demonstrates that the Ministry’s advice was largely ignored.

Figure 4. Seven public institutions perceived as highly corrupted by Biskek residents, 2019

Note: the actual score of perceived corruption ranges from +100 to -100, with bigger negative number associated with higher level of corruption.

Source: The “Index of trust of the population, second half of 2019,” Statistical Committee of the KR, 2020.

As of August 24, 2020, the number of total confirmed coronavirus cases in Kyrgyzstan stands at 43,245, out of which 1,057 are deaths. In terms of official cases, Kyrgyzstan has the second highest number of infections after Kazakhstan in Central Asia. However, in terms of mortality rate per 100,000 people, Kyrgyzstan is in first place in the region, occupying leading positions in the entire Eurasian zone on this number.

A woman walking in Dordoi Bazaar, a wholesale and retail market in Bishkek. Photograph by the authors.

In the same vein, it is equally worth noting that within the context of the actual health crisis, significant reconfigurations of social relations and solidarity networks are taking place. Indeed, on the one hand, in the face of the rapid spread of cases of infections, self-help unions—mostly made up of young people—have been formed in order to relieve the medical system which found itself on the verge of collapse under the weight of the crisis. In this regard, several hotels, schools, and sports centers were turned into makeshift hospitals in Bishkek with the help of active young volunteers as well as financial support provided by the local community of entrepreneurs. But the pandemic equally takes its toll on the country’s vibrant civil society as it disrupts day-to-day solidarity networks. For example, Guljan, a 60-year-old woman and resident of a village in Talas, a region in the north-west of Kyrgyzstan, says she has observed significant changes in the behavior of her neighbors: “The fear of contracting the virus forces everyone to live in isolation; if formerly the villagers often paid each other casual, daily visits, today we are becoming more and more indifferent; each family decides to stay away from the community.”

One of the cornerstone challenges that Kyrgyzstan faces within the context of the current health crisis is related to the fact that COVID-19 seems to altogether up-end the deep-rooted, day-to-day religious practices in Kyrgyzstan. In particular, this concerns the cases of flouting funeral customs and norms, a rather unprecedented event: “This pandemic, it changes and shakes up everything. People are afraid, we cannot trust even our family members and relatives because we are not sure whether they are carriers of the virus or not,” says Aidarbek, a 36-year-old dentist and resident of Bishkek whose uncle passed away on July 16, 2020, from cancer. “Even though my uncle wasn’t affected by coronavirus, most of his relatives and acquaintances could not attend his funerals out of the fear of contracting the virus or infecting someone.” Hence, out of 200 people expected, around 40 attended the Aidarbek’s uncle funeral.

As a matter of fact, in a society such as Kyrgyzstan’s where, as Kathleen Collins argues, clanic mechanisms and networking play a vital role in the distribution of economic and political favors, social gatherings represent an essential tool for individuals to build and expand on their informal contacts to access crucial socioeconomic resources. Therefore, the fact that COVID-19 significantly thwarts individuals’ opportunities to fully benefit from their social capital illustrates the extent of the crisis’ impact on the social and economic lives of the population.

Concluding remarks

For the time being, Kyrgyzstan is walking a tightrope between recovering economic activity, indebtedness, and a new wave of contamination. Furthermore, there is every likelihood that the COVID-19 crisis will result in the emergence of popular discontent, expressed massively through social networks, attacking the dilettante management of the crisis (e.g., massive funds received from abroad, but no infrastructure hospital set up before July). This discontent has been recently aggravated by the claims of the Kyrgyz government to toughen its legislation on media. More specifically, the state parliament in June passed a controversial bill called “On manipulating information,” which purportedly seeks to address the problem of inaccurate information spreading online by enabling the authorities to restrict or block access to internet sites as well as shut down social media accounts without the need for a court decision. The bill produced a strong public backlash, with its opponents comparing the law to legislations in effect in neighboring authoritarian states, notorious for their practices that openly flout the rights of their citizens’ freedom of speech. In light of the backlash, and although the Kyrgyz President, Sooronbai Jeenbekov, has returned the bill to parliament on the grounds that the legislation requires further rectifications, it seems the final ratification of the law is simply matter of time.

[1] Authors’ interview with anonymous lawyers.

[2] Entitled Kyrgyz Republic COVID-19 Poverty and Vulnerability Impacts. Micro-micro simulations of COVID-19 shock, the study, which has not yet been the subject of an official publication, was presented on June 30, 2020, during the online applied training “Poverty and Welfare Analysis” organized by the World Bank Kyrgyzstan from June 15–30, 2020.

Bibliography

AKIpress Central Asian News Service. “Kyrgyzstan’s Public External Debt Makes around 50% of GDP – Report.” July 20, 2020. https://akipress.com/news:645709:Kyrgyzstan_s_public_external_debt_makes_around_50__of_GDP_-_report/ (accessed August 8, 2020).

Akisheva, Asylai. “Women Face-to-Face with Domestic Abuse during COVID-19 Lockdown: The Case of Kyrgyzstan.” Central Asia Program, August 19, 2020 https://centralasiaprogram.org/archives/16842 (accessed August 28, 2020).

Asanov, Bakyt. “Dollar za odin den’ podorozhal na 13 somov”. Azattyk Radio Free Europe, March 19, 2020. https://rus.azattyk.org/a/30497677.html (accessed July 20, 2020).

Blondin, Suzy. “An Environmentally-Fragile and Remittance-Dependent Country Facing a Pandemic: The Accumulation of Vulnerabilities in Kyrgyzstan.” Environmental Migration Portal. 2020. https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/blogs/environmentally-fragile-and-remittance-dependent-country-facing-pandemic-accumulation (accessed July 25, 2020).

Collins, Kathleen. Clan Politics and Regime Transition in Central Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511510014.

Djanibekova, Nurjamal. “Kyrgyzstan: Anxiety creeping, but few can afford luxury of COVID-19 panic.” Eurasianet, March 20, 2020, https://eurasianet.org/kyrgyzstan-anxiety-creeping-but-few-can-afford-luxury-of-COVID-19-panic (accessed July 25, 2020).

Dubashov, B., A. Mbowe, S. Ismailakhunova, and S. Zorya. “Kyrgyz Republic: Weak Growth Despite Emerging Regional Opportunities – With a Special Focus on Agricultural Potential for Growth and Development (English).” World Bank, Washington, DC. February 7, 2019. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/723081549553196953/Kyrgyz-Republic-Weak-Growth-Despite-Emerging-Regional-Opportunities-With-a-Special-Focus-on-Agricultural-Potential-for-Growth-and-Development.

Holmes, Alexander, Barbara Illowsky, and Susan Dean. 2017. Introductory Business Statistics. 1st ed. XanEdu Publishing Inc. https://openstax.org/books/introductory-business-statistics/pages/1-introduction.

Ibraimova, Ainura, Baktygul Akkazieva, Aibek Ibraimov, Elina Manzhieva, and Bernd Rechel. 2011. “Kyrgyzstan. Health System Review.” Health Systems in Transition 13 (3): 1–151. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/142613/e95045.pdf

International Monetary Fund. “Real GDP Growth, Kyrgyzstan.” https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/KGZ?year=2020 (accessed July 29, 2020).

Imanaliyeva, Ayzirek. “Kyrgyzstan: Internet Gagging Bill Sails through Parliament.” Eurasianet, July 26, 2020. https://eurasianet.org/kyrgyzstan-internet-gagging-bill-sails-through-parliament (accessed August 8, 2020).

Jauer, Marcos. “Savons Nous Encore Faire Confiance?” Courrier International, July 8, 2020. https://www.courrierinternational.com/article/la-une-de-lhebdo-savons-nous-encore-faire-confiance (accessed July 20, 2020).

Joldoshev, Kubanychbek. “Vybory-2020: Imidzh i uroven’ partiy, idushchikh v Zhogorku Kenesh” Azattyk Radio Free Europe, July 27, 2020. https://rus.azattyk.org/a/30748686.html (accessed August 8, 2020).

Kapuchenko, Anna. “Odnim kadrom: V Kyrgyzstan pribyli mediki iz Kitaya dlya pomoshchi v bor’be s koronavirusom” Kloop.Kg. April 20, 2020. https://kloop.kg/blog/2020/04/20/odnim-kadrom-v-kyrgyzstan-pribyli-mediki-iz-kitaya-dlya-pomoshhi-v-borbe-s-koronavirusom/ (accessed June 10, 2020).

Kuehnast, Kathleen K., and Nora N. Dudwick. Better a Hundred Friends than a Hundred Rubles?: Social Networks in Transition – The Kyrgyz Republic. World Bank Publications, 2004. https://books.google.kg/books/about/Better_a_Hundred_Friends_Than_a_Hundred.html?id=8Z-yJegFFXkC&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Kudryavtseva, Tatyana. “Kyrgyzstan Asks Creditors to Suspend Payment of Debt.” 24.Kg News Agency, Bishkek. July 23, 2020. https://24.kg/english/160424__Kyrgyzstan_asks_creditors_to_suspend_payment_of_debt/ (accessed July 30, 2020).

Kuvatova, Aigul. 2020. “Zakon o manipulirovanii informatsiey. Vsem molchat’!” 24.Kg News Agency. June 26, 2020. https://24.kg/obschestvo/157446_zakon_omanipulirovanii_informatsiey_vsem_molchat/ (accessed September 20, 2020)

Masalieva, Jazgul. “Not a single case of coronavirus registered in Talas region of Kyrgyzstan.” 24.Kg News Agency, Bishkek. April 28, 2020. https://24.kg/english/151309_Not_a_single_case_of_coronavirus_registered_in_Talas_region_of_Kyrgyzstan/ (accessed July 20, 2020).

Ministry of Jurisdiction of Kyrgyzstan “Postanovleniye o merakh po predotvrashcheniyu ugrozy vozniknoveniya i rasprostraneniya koronavirusnoy infektsii (COVID-19) na territorii Kyrgyzskoy Respubliki”, March 17, 2020. http://cbd.minjust.gov.kg/act/view/ru-ru/157444?cl=ru-ru (accessed August 20, 2020).

“Mortality Analyses,” John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, August 25, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality (accessed August 25, 2020).

National Statistical Committee of Kyrgyz Republic. “Indeks doveriya naseleniya za II polugodie 2019g”. http://stat.kg/media/files/1955e432-e02e-4efe-8da3-897822485d51.xls (accessed July 20, 2020).

Nurmatov, Ernis. “Som « poplyl » vsled za rublem ». Kurs dollara v Kyrgyzstane preodolel psikhologicheskiy bar’er”, Azattyk Radio Free Europe, March 11, 2020. https://rus.azattyk.org/a/kyrgyzstan-dollar-podorojal/30480882.html (accessed July 20, 2020).

Official site on coronavirus in Kyrgyzstan. August 24, 2020. https://covid.kg (accessed August 25, 2020).

Orlova, Maria. “Coronavirus pandemic: Russia completely closes its borders.” 24.Kg News Agency, Bishkek. March 29, 2020. https://24.kg/english/148412_Coronavirus_pandemic_Russia_completely_closes_its_borders/ (accessed July 25, 2020).

Osmonalieva, Baktygul. 2020. “President of Kyrgyzstan Sends Law on Manipulating Information for Revision.” 24.Kg News Agency. July 25, 2020. https://24.kg/english/160731__President_of_Kyrgyzstan_sends_law_on_manipulating_information_for_revision/ (accessed September 20, 2020)

Paul, Nathan Southern and Lindsey Kennedy. “Central Asian States Can’t Hide the Coronavirus Any Longer.” Foreign Policy, March 20, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/20/central-asian-states-cant-hide-coronavirus-kazakhstan-uzbekistan-kyrgyzstan-tajikistan-turkmenistan/ (accessed July 20, 2020).

Podolskaya, Darya. “New virus in China: All flights to China temporarily suspended.” 24.Kg News Agency, Bishkek. January 27, 2020. https://24.kg/english/141701__New_virus_in_China_All_flights_to_China_temporarily_suspended/ (accessed July 25, 2020).

Pomfret, Richard. The Central Asian Economies in the Twenty-First Century: Paving a New Silk Road. Princeton University Press, 2019. https://books.google.kg/books/about/The_Central_Asian_Economies_in_the_Twent.html?id=8UZkDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Putz, Catherine. “Death and Denial in Turkmenistan.” The Diplomat, August 19, 2020. https://thediplomat.com/2020/08/death-and-denial-in-turkmenistan/ (accessed August 24, 2020).

Reuters. “Central Asia Struggles With Resurgent Coronavirus After Reopening.” New York Times, July 8, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2020/07/08/world/asia/08reuters-health-coronavirus-centralasia.html (accessed July 30, 2020).

Reuters. “Kyrgyzstan extends state of emergency until May 10.” April 28, 2020. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-health-coronavirus-kyrgyzstan/kyrgyzstan-extends-state-of-emergency-until-may-10-idUKKCN22A21J (accessed July 30, 2020).

Satke, Ryskeldi. “The Downside of Foreign Aid in Kyrgyzstan.” The Diplomat, June 10, 2017. https://thediplomat.com/2017/06/the-downside-of-foreign-aid-in-kyrgyzstan/ (accessed August 25, 2020).

Suyarkulova, Mohira. “‘Your traditions, our blood!’: The struggle against patriarchal violence in Kyrgyzstan.” OpenDemocracy, April 2, 2020. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/your-traditions-our-blood-the-struggle-against-patriarchal-violence-in-kyrgyzstan/ (accessed August 20, 2020).

US Embassy Bishkek. “Health Alert: Kyrgyz Republic COVID-19 Update,” March 26, 2020, https://kg.usembassy.gov/health-alert-u-s-embassy-bishkek-march-26-2020/ (accessed July 20, 2020).

World Bank. “World Bank Predicts Sharpest Decline of Remittances in Recent History.” Press Release. April 22, 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/04/22/world-bank-predicts-sharpest-decline-of-remittances-in-recent-history (accessed July 20, 2020).

World Bank. “World Development Report, Attacking Poverty.” Oxford University Press, 2000/2001. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/11856/World%20development%20report%202000-2001.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed July 20, 2020).

World Bank. “Kyrgyz Republic: From Vulnerability to Prosperity. A Systematic Country Diagnostic, 2018.” International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank, 2018. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/516141537548690118/pdf/Kyrgyz-Republic-SCD-English-Final-August-31-2018-09182018.pdf (accessed July 20, 2020).

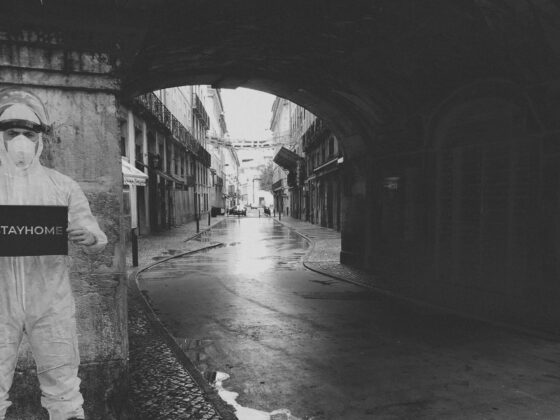

Featured Photo by Irene Strong