Negotiating Gender in Central Asia: The Effect of Gender Structures and Dynamics on Violent Extremism

Edited by Peter Knoope and Seran de Leede

With estimates ranging from 5,000 to 7,000 men and women migrating to Syria and Iraq from the Central Asian states since April 2013, the region ranks third in supplying foreign recruits for jihadist groups active in the Syrian conflict.1 Six percent of, or around 620, Central Asian women reportedly are affiliated with the Islamic State (IS).2 Additionally, Central Asian nationals have been involved in attacks outside of the region, including in Istanbul, St. Petersburg, Stockholm, and New York. These developments have contributed to an increased (research) interest in issues around radicalization and the appeal of jihadist groups in Central Asian states. To what extent gender dynamics and dimensions are relevant in understanding violent extremism is, however, less explored or addressed. By adopting a gender-sensitive approach, this Special Issue builds on the work that has been done on the subject so far. It hopes to inspire other scholars to take a similar approach and to generate discussion among professionals working on violent extremism in the region in terms of recognizing the relevance of gender in relation to curbing and preventing violent extremism.

This Special Issue paints a picture that confirms a general trend of a reduction of political space in the region, especially for women. A call for the return to traditional values combined with the continued lack of religious freedoms and space increasingly leads to a deterioration of the position of women in society, shaping women’s individual options and choices -including, in the context of violent extremism, options and choices in respect of joining Daesh. While domestic violence, misogyny, and a culture of repression of women do not (directly) push women towards violent ideologies, women can end up in (support of) violent extremist groups due to the impact of these phenomena on their lives. The collection of essays in this Special Issue points out that the recognition of the complexity of this matter is an important element for any policy targeted at the prevention and curbing of violent extremism in the region. Simply taking the ideology as a point of reference will not guide an effective approach. In addition, repression by the state, including state-condoned misogyny, produces an outcome that generates the securitization of parts of the population that opposes the repression, denying them the space to have their voices heard. At the same time, this paralyzes and silences those actors that can play important roles in peacebuilding and efforts aimed at the prevention of violent extremism.

There are many reasons why inclusiveness, using the perspectives of both men and women, in any research and policy approach is beneficial. This Special Issue demonstrates that in the domain of security, this is even more the case because exclusion is damaging from many angles. The structural exclusion of women harms at least half the population; it allows for strategic advantages of violent actors; it alienates those organizations working for (gender) equality and peace from societal dynamics; and it ignores the real motives and catalyzing factors that lead to counterproductive policies and approaches. This collection of essays demonstrates that, violence, hyper-masculinity, and misogyny are part of the same toxic mixture that can produce an environment conducive to violent extremism. Ignoring this, especially in terms of policy, may very well increase the problem. Instead, exploring, recognizing, and understanding specifics about gender norms and structures and how violent extremist groups benefit from and exploit these may prove a more useful approach.

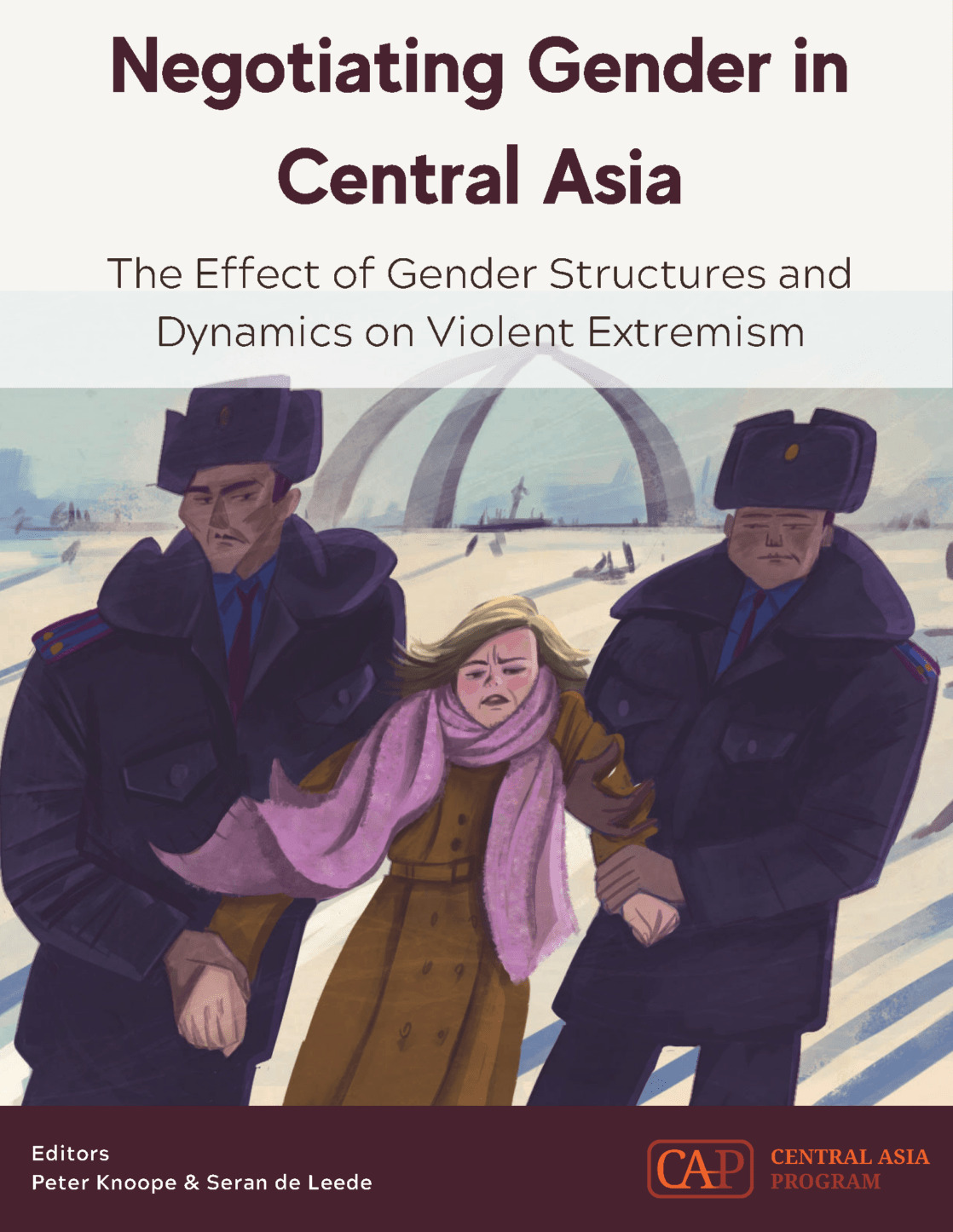

Illustration: “Self-Portrait,” by Tatyana Zelenskaya. On International Women’s Day, celebrated on March 8, a women’s march is held annually in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. During the 2020 march, a group of masked right-wing radical men attacked the march participants, including the artist. The police officers who arrived on the scene detained only the participants in the march. The artist’simpression was that the police were working together with the attackers. She drew this picture immediately after the events and posted it on social networks in order to somehow speak out about what had happened.

Fieldwork for Noah Tucker’s chapter Uzbek Women in the Syrian Conflict: First-Person Narratives and Gendered Perspectives on Mobilization and De-Mobilization” was supported by a generous grant from DAI Global.