Author: Li You

Source: Sixth Tone

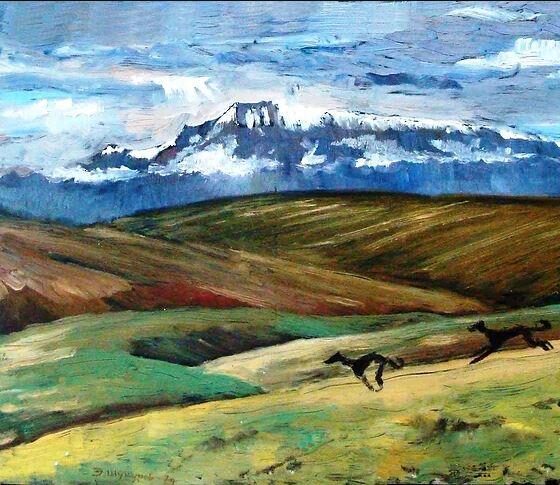

As the nomadic people of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region begin their annual migration to warmer pastures, the snow has yet to fall.

For thousands of years, generations upon generations of these herdsmen have traversed China’s northwest in search of greener pastures. Photographer Qian Han accompanied a group of these nomads, together with their flocks of sheep, on a 180-kilometer pilgrimage to the place where they would spend the coldest months of the year, where the land is flatter, the weather milder, and the snow — when it falls — thinner, so the livestock can nibble at the grass underneath.

“No snow this year meant there wouldn’t be enough water for their journey,” said Qian, who for six years followed the herdsmen’s seasonal migrations through Xinjiang’s mountainous Altay Prefecture. “The water shortage was going to make the migration even harder for the herdsmen, who dine in the wind and sleep outdoors,” the Shandong-based photographer told Sixth Tone.

To quench their thirst on the arduous journey, the herdsmen have traditionally relied on ice, which they collect in knitted bags from frozen rivers at the start of their journey and replenish at thawing streams along the way. With temperatures plummeting well below freezing around this time of year in Xinjiang, the ice remains solid until the parched herdsmen apply heat, whether from a fire or their own bodies, to get water. To ensure that the nomads have enough to drink, Qian said, they even receive ice delivered from local officials by car.

However, when crossing arid regions such as the steppes between the Irtysh and Ulungur rivers, the nomads rely heavily on snowfall, according to Luo Yi, an associate professor of anthropology at Xinjiang Normal University who focuses on the region’s nomadic communities. There is speculation that the lack of precipitation this winter may be related to global climate change, though Luo told Sixth Tone that more research is needed to vet this theory. He admits, however, that climate change adds a degree of uncertainty to the nomadic lifestyle because of the unexpected weather events and unbalanced ecosystems that tend to go hand in hand with it.

Although many nomadic communities in China continue their tradition of moving from one area to another throughout the year, development and urbanization have deeply impacted these groups, both socially and economically. Government policies such as resettlement programs — whereby formerly nomadic people are installed in established communities — have taken a toll on their way of life. The number of migrating livestock in Xinjiang, too, has declined over the years, partly due to grazing bans and resettlement projects, the deputy head of the region’s animal husbandry office told a local TV network last month.

“Nomadic communities are going through a rapid transformation,” said Luo, the anthropologist. “There needs to be a process for them to adjust, because [resettlement] influences not only how they make a living, but also their daily routines and ideological systems. For many nomads, [adapting] can be hard.” However, according to Luo’s research, there are also many herdsmen in the community who look forward to settling down and assimilating into urban or suburban communities, as such lifestyles can lower the risks of contracting diseases or encountering natural disasters. In addition, Luo said, sedentary people tend to have better access to medical care.

Qian, the photographer, has witnessed the dramatic transformations among the nomads firsthand. “The things that I saw six years ago have disappeared now,” he said, recalling a mostly bygone era when a whole family might pack up all their belongings and move, on the backs of horses and camels, their children and their elders in tow. Now, only a few lone wolves still migrate on horseback, as more and more people are opting to transport their livestock by truck, Qian said. “In a few years, as their lives improve, maybe you’ll see all of them turning to trucks.”