By Dr. Paul Woods

Dr. Paul Woods is a Research Tutor at the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies in Oxford. His principal research interest is contemporary activism in Central Asia. He holds one PhD in the Cognitive Linguistics of Chinese and another in the Public Theology of Migration in East Asia. He is a relative newcomer to things Central Asian, but is dedicated to and loving this new geographical and cultural focus.

Dr. Paul Woods is a Research Tutor at the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies in Oxford. His principal research interest is contemporary activism in Central Asia. He holds one PhD in the Cognitive Linguistics of Chinese and another in the Public Theology of Migration in East Asia. He is a relative newcomer to things Central Asian, but is dedicated to and loving this new geographical and cultural focus.

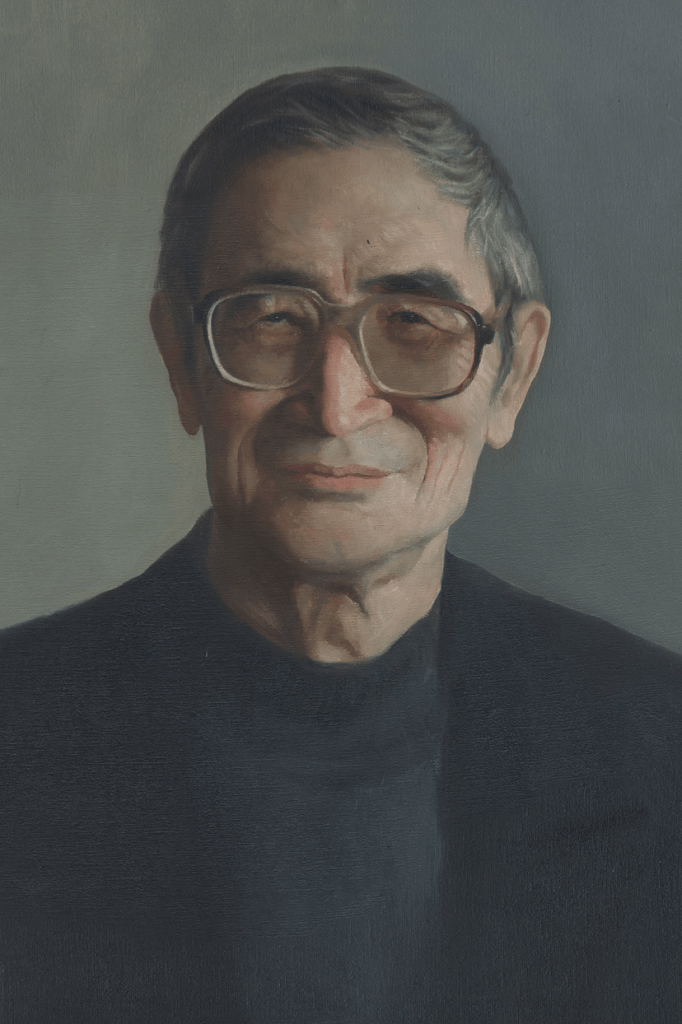

This paper looks at the ecological thought of Emil Dzh. Shukurov (1938-2019) and how his theories relate to his native Kyrgyzstan and the broader world. It relies on two extracts from his book Sochineniia, or Compositions, as primary sources.[1] The article begins with a brief portrait of Shukurov and then outlines his analysis of the reasons for the current environmental crisis. Next, it explores how the nomadic worldview encourages respectful interaction with nature—perspectives that Shukurov believes provide an answer to our environmental crisis. True to his own nature, Shukurov offers nomadism as a corrective for what he sees as globalization from the West; yet does not insist that the traditional ethos of the Kyrgyz people should be imposed around the world. Here I present Shukurov’s thought on his own terms, letting him speak for himself. The brevity of this article and my desire to honor this man mean that I have added a few observations of my own but have resisted the temptation to bring him into dialogue with scholars from other discipline

The Life and Work of Emil Shukurov

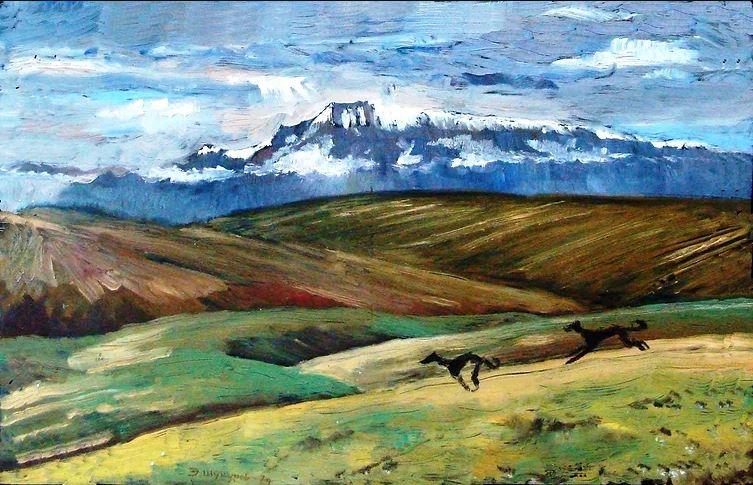

Emil Dzhaparovich Shukurov (1938-2019) was a Kyrgyz academic and environmental activist. He began his career as a biologist and became a scientist and environmental advisor to the Kyrgyz SSR government in 1963.[2] While working for local and international environmental and conservation groups, Shukurov was a prolific author of books and academic papers. He also gave public and academic lectures and served as an environmental consultant for various local and international NGOs. Apart from his passionate and focused work in science and policy, he was also a poet and artist.[3] Shukurov loved his country, appreciating its beauty and understanding the environmental challenges it faced. He also witnessed the struggles of his newly independent nation as it transitioned to a market economy. As a Kyrgyz academic, he saw himself as representative of not only Kyrgyzstan but of all countries that lack wealth and influence on the world stage. He believed that within his country’s own culture and traditions, there exist both a powerful critique of factors that led to our current environmental crisis and useful resources for responding to it.

An Orientation to Shukurov’s Thought

One of the best introductions to Emil Shukurov and his environmentalism is a YouTube video, “Silence of Words,”[4] produced in 2016 by the Bishkek-based educational NGO, the Taalim-Forum.[5] The piece is a combination of Shukurov’s own views and commentary from other public figures in Kyrgyzstan. In the video, filmmaker and author Talip Ibraimov notes that although Shukurov was first and foremost a scientist, his works integrated biology, geography, natural sciences, and philosophy into an organic whole. Next, the rector of the Kyrgyz Civil Service Academy Chingis Shamshiev opines that apart from his scientific knowledge, Shukurov was also steeped in the history and tradition of the Kyrgyz people and had a deep understanding of the workings of the modern nation-state. Finally, Amagul Djumabaeva of the Taalim Forum explains that Shukurov sees the environmental crisis as spiritual in some way, noting his warning that humankind must not lose its link with nature.

With these comments to set the scene, I now turn to Shukurov’s own ideas presented in the video. He believes that humanity has taken what he calls a “dead-end road” leading to “societal degradation”. He critiques the consumer society that values entertainment above all and only cares about nature conservation if it brings profit or tourism. According to Shukurov, the modern mindset is that if nature does not entertain or bring some financial benefit, then it does not have the right to exist. Such a mentality has produced a form of selfishness that affects not only how we connect with nature but also how we relate to each other. He sees it as a spiritual degeneration that impacts the whole global civilization and will lead humankind to the deadlock mentioned above.

Shukurov’s response is to turn to the traditions of the Kyrgyz people. He claims that for centuries local culture has emphasised harmonious relations among people and between humankind and nature and that one of the most important tasks of our time is to return to our ancestors’ positive orientation to nature. He wishes to revitalize the ancient ways within new frameworks, so modern people can be faithful to their great history.

Understanding the Environmental Crisis: Shukurov on Nature and Culture

The following section explores Shukurov’s diagnosis of the causes of the current crisis, drawing from his essay, Nature, Human Culture, at the Red Line, part of Compositions. In the essay, Shukurov structures his main argument into three binary oppositions: humanity versus nature, civilization versus culture, and globalization versus civilizations. Each dyad is complex and interwoven with the others.

Man vs. Nature

According to Shukurov, the fundamental cause of the environmental crisis is to be found in the opposition between man and nature. In his essay, Shukurov begins by describing how humanity’s modern existence is paradoxical: a part of nature while also, in some sense, existing outside of it. Humanity is unique in that our intelligence and the nature of our society allow us to go beyond the intrinsic bounds that limit all other species and thus change our physical surroundings. However, the price to pay for this liberty is what Shukurov calls “living outside nature” and the associated delusion that we can live independently of it.

This dualism—humankind’s desire to exploit nature and dependence upon the natural order—means that our attempts to portray ourselves as kings are unwise. Humankind has the power to take what it wants from nature, but this is short-sighted. Physically, we are just another form of animal created by God and it is not for us to decide which species live or die. Our overcoming of “species limitations” should produce in us a strong sense of responsibility rather than entitlement.

Living outside of nature has led to an antagonistic relationship with it. Humankind’s desire to control nature and the attendant tendency toward exploitation have reduced the scope of our existence. On metaphorical islands which we have built within an “ocean of decay of life,” we try to preserve and enhance our way of life. Shukurov reminds us that although we try to create life by our own human efforts, in reality it is created by “wild nature.” Indeed, nature has been creating life for aeons, including our own. There is a contrast between the life-creating and sustaining power of “wild nature” and the regions of death, waste, and destruction associated with what humanity thinks are “cultural lands”. In fact, in these lands nature is commodified and exploited for humanity’s perceived needs. If we define human personhood by the ability of humankind to set itself apart from nature, then nature’s inherent importance is denied and it becomes simply raw material.

Culture vs. Civilization

Shukurov’s second opposition is social: a rivalry between “culture” and “civilization.” The juxtaposition of these two concepts provides a critique of reductionist thought and sets the scene for his subsequent discussion of globalization. According to Shukurov, culture is “what sets the person apart from nature,” the way human beings understand their social and physical environment, augmenting our natural instincts to regulate our social behavior. If “culture” relates primarily to the regulation of human behavior in a natural environment, then “civilization” regulates behavior in “extranatural situations.” According to Shukurov, the framework of civilization works well for “artificially created,” settled societies that are cut off from and insensitive toward nature. Over time, the more advanced a civilization becomes, the more distant from “wild nature.”Shukurov believes civilized societies regard early cultural practices that restrained humankind’s impact on nature as primitive. And as civilizations become orientated toward progress, development overwhelms and plunders culture. As the gap between civilization and culture widens, the latter is left on the periphery. And yet civilization itself is derived from culture and relies on cultural underpinnings for its own identity and purpose.

As civilization became the primary model for interacting with the social world, it became overly simplistic. Shukurov argues that a worldview focused primarily on human relations outside of nature is inherently impoverished and ignorant about the totality of our existence. Such reductionism is detrimental to understanding nature and our place within it. The simplistic nature of civilization means that it is doomed to undermine the very societies that rely upon it to regulate their individual and collective behavior.

Two specific elements of civilization are politics and economics. For Shukurov, one is simply about hanging on to power while the other seeks only to make profit. In the world today, neither element has the ability to regulate human behavior in a way that facilitates the flourishing of both humanity and nature, which Shukurov calls “Life with a capital L”. Civilization has no time for, what Shukurov sarcastically calls, the “savage deification” and “spiritualization” of traditional cultures; it sees the world only in material or economic terms. The arrogance of this kind of civilization sometimes anthropomorphizes animals and objects, projecting human traits onto them, but is unwilling to relate to these entities on their own terms. Civilization never sees nature as an equal partner.

Globalization vs. Civilizations

Shukurov’s third dyad is both geospatial and philosophical, placing contemporary globalization against local civilizations. Having framed cultures and civilizations and explored the damaging effects of the latter, Shukurov makes a trenchant criticism of globalization, calling it a “single civilization” that has consumed older, local civilizations. Globalization is portrayed in opposition to civilizations, but yet, even in its destructive development, it relies on civilizations of the past to frame its future. What civilizations previously did to culture is now being done to them by globalization.

Earlier, geographically isolated civilizations that neglected their relationship with nature to the point of environmental destruction and societal extinction would not endanger the whole human race. Now, Shukurov argues, the corrosive power of globalization can be felt across the whole planet and threatens all of humankind. It is a mega-civilisation with a destructive force that has no geographical limitation.

In addition, globalization functions at such a high level that it may be less willing and less able to interact with local cultures, even in a predatory sense. The reductionist understanding of human relations and environmental risks together with the convenience and impoverished content of simplistic communication risk causing ignorance of the outside world and an overall dumbing down of society. And in an age of instant communication, individuals and societies who cannot grasp anything beyond simple images and short summaries are unable to see how globalization is affecting the planet.

For Shukurov, globalization includes “the cult of consumption and overconsumption, the Achilles heel of civilization.” As globalization expands, it transmits the lifestyle and material aspirations of Western consumer civilization to the rest of the world, further endangering the planet. Earth’s resources are limited and there is an imbalance in resource consumption between developed and underdeveloped countries.

Shukurov claims that development strategies exist to preserve the lifestyle of well-off countries at the expense of the rest of the world. He suggests that consumerism can justifiably be compared to alcoholism or drug addiction, but points out that the causes and effects of consumerism are harder to diagnose and address. Shukurov also considers the political consequences of globalization. To him, the high points of human endeavour are religion, art, and science, all of which require investment of time and energy to understand and develop. By contrast, politics focuses on the short term . Also, political power is constrained by state borders—which are becoming irrelevant in light of both globalization and the environmental crisis—and by electoral cycles or the longevity of regimes.

Unfortunately, while politics is constrained, the effects of political decisions and policies on the environment are much less limited. From his examination of the human condition at individual, community, and global levels, Shukurov concludes that our attempts to locate ourselves outside of nature have led ultimately to globalization, or “a march of modern civilisation away from life, into nothing.” In the next section, I explore Shukurov’s view of nomadism, which he claims is a way forward.

Addressing the Environmental Crisis: Shukurov on Nomadism

I now turn to Shukurov’s discussion of nomadism, drawing on his essay, Nomadism: A Perception of the World for the 21st Century, which can also be found in the book, Compositions. In it, he lays out how nomadism responds to the three conceptual pairs identified above (nature versus culture, culture versus civilization, and globalization versus civilization).

Citing famous Kyrgyz literature and stories, including the Epic of Manas, stories about the ancient hero Kojojash, and the Soviet-era writer Chingis Aitmatov, Shukurov makes the argument that the nomadic worldview is an answer to the crisis of globalized climate change and destructive consumerism. Nomads have, what Shukurov calls, “a constant and lively connection with nature.” By living close to and as a part of nature, rather than outside it, and by respecting nature’s natural rhythms, nomads are attuned to the signs provided by animals and plants, giving them an understanding of what is happening in their environment.

Shukurov’s use of the word “foresight” is evocative of folk wisdom, while the word “predict” is suggestive of science; he seems to bring together what the Western mind might separate. He explains that nomadic people enjoy nature, understand species diversity, and have specific terms for each physical geographical feature in their area. This knowledge is passed down from generation to generation, an education that is both practical and “emotionally colourful.”

An attitude of respect toward nature means that nomadic people have developed basic rules for living off the land. Specifically, they periodically change pastures to avoid excessive grazing, preserving the land for future seasons. These fundamental rules and rhythms are set by the environment: a natural law that nomads accept rather than try to change. The difference between nomadism and the mentality of the “modern man intoxicated by his power,” is that the nomad tries to live in harmonious communication with nature, while the modern man sees nature as a commodity. Shukurov warns us that “retribution is inevitable” we can only stand outside of nature and exploit it for so long.

For Shukurov, Kyrgyz nomadism offers a contrast to the relationship between humankind and nature that brought on our environmental crisis. However, Shukurov is modest and realistic in his criticism of globalization and in his advocacy for a more holistic, nomadic approach to living. He does not make a “sweeping, total condemnation of Western civilization and sedentary culture,” and acknowledges their great contributions to humankind. Rather, he opposes globalization’s “arrogance of universalism” and over-reliance on market relations which are unable to cope with a world with many complex dimensions and phenomena. Globalization’s preoccupation with the market economy leaves no place for understanding what Shukurov calls the “true values of the world”—values found in nomadism, that could help us find a way out of our environmental, and spiritual, crisis.

To narrow considerations of “rationality” must be added aesthetics and ethics, the latter two associated with “truly cultured” people. With this framework in mind, he asserts that people avoid behaving wrongly not out of fear of external punishment but out of an aversion to unpleasant internal reactions. He claims that behavior that violates rationality, aesthetics, or ethics causes the offender to feel distorted inside and can damage a person’s sense of self and worldview. Shukurov believes that a person’s natural conscience, nature’s influence on humankind, the role of communities in natural settings, and mankind’s influence on nature are all interconnected, as expressed in elements from the Abrahamic religions. He claims that nature is the language through which God communicates with humankind, and nomads know the importance of being able to understand that language. Like nomads, we should try to understand nature and its laws and use rationality, aesthetics, and ethics to attune ourselves better to its way of communication.

For the nomad, every living entity is part of nature’s whole and each part has its role in “the incessant, tireless activity of nature”: maintaining life. People in “civilized lands” like to surround themselves with only selected, familiar species from nature. In other words, as the modern human reads from “the great book of nature,” pages are missing, having been torn out by the selective reader. Now the book’s message is neither complete nor coherent. According to Shukurov this is the Tower of Babel, akin to a “Babylonian pandemonium” where people have lost the ability to hear God, communicate with each other, and relate to nature itself. It is a form of blasphemy which seeks victory over nature, its actions and attitudes incompatible with the nomadic consciousness. The nomad cannot declare independence from nature and neither can he rip out its pages.

Instead of ripping pages from the book of nature, Shukurov recommends getting to know nature through the concept of the jailoo, a summer pasture retreat in the hills. The jailoo is a place of both work and pleasure, a place to reconnect with people, nature, and oneself. It is a combination of patience and work, a paradox of restraint and enjoyment. In contrast to the harshness of winter, the jailoo offers a respite, a place for animals to graze and an ease of life that is only enhanced by a community lifestyle. At the jailoo, there is mutual support, with everyone pitching in together, and hospitality given to outsiders. It is a symbol of a sustainable lifestyle because its location and limited resources bring constraints, but the open spaces and opportunities for rest speak of pleasure. The cycle of the seasons and annual migration, with harsh winters and times of rest in the jailoo, are natural ups and downsthat have inculcated patience and harmony in nomadic peoples. For Shukurov, there is much that people today could gain from this practice, such as a proper balance between work and pleasure and a connection to our ancestral past.

The nomadic lifestyle, as represented by the jailoo,is a combination of the practical and aesthetic. Shukurov explains that nomads have few possessions, but what they do have are usually things of great beauty made from natural materials. Even at the level of simple household items, rationality, aesthetics, and ethics are combined. The nomadic lifestyle also produces neither excessive waste nor pollution and seeks not to harm the environment on which people depend for survival. It is the antithesis of globalization’s consumption-driven way of life that values an overabundance goods and materials and gives no thought to throwing things away.

While Shukurov is proud of his Kyrgyz heritage and believes the values of the nomadic lifestyle and the productive recreation of the jailoo have much to commend them, he does not advocate a return to the past and a rejection of the many benefits of modern civilization. He does not believe that a true Kyrgyz needs only a horse, a yurt, beshbarmak (Central Asian meat noodles), and a komuz (three stringed guitar) to be happy. And although he condemns the all-consuming, domineering nature of globalization, he does not wish to impose his own nomadic culture on the rest of the world. But the wisdom of the Kyrgyz tradition provides many broad principles of sustainability and respect for nature that can be implemented by cultures around the world.

Conclusion

Whatever way we proceed, we would do well to bear Shukurov’s basic tenets in mind. First, humankind is physically dependent upon nature: even though human intelligence grants us a degree of transcendence unique among sentient creatures, we cannot control the natural world without consequences. Second, understanding our dependence on nature should move us to humility, as we are both participants in and stewards of nature. Third, as cultures advance and technologies develop, we cannot pick and choose elements of them that we feel fit in with a bottom-line, materialistic worldview. It is important, like the nomad, to place value in aesthetics and ethics. Finally, we need our own versions of the jailoo that can teach us hard work and pleasure, sustainability, and community as well as the rhythms of existence and the joy of sharing. This rounded and organic worldview could protect us against the dangers of neoliberal, consumerist globalization, which consumes cultures as quickly as it does our natural environment.

In his book Compositions, Emil Shukurov presents his ideas about the origins of our ecological crisis and advocates that, to save our planet, we need to adopt principles from the nomadic way of life that teaches a co-existence with nature. His fundamental thesis is that humankind is alienated from nature and, as a result, civilizations have developed a reductionist concept of society’s place in the natural order. While previous civilizations made mistakes that affected local environments and populations only, the mistakes of today’s globalized society affect every area of our planet. The nomadic mentality preserves the relationship between people and nature; builds community; combines aesthetics, ethics, and rationality; and attunes society to the environment’s natural rhythms. While many people are sympathetic to the green movement and critiques of globalization are not new, the work of Shukurov is noteworthy because he finds parallels and draws solutions from a local culture far removed from the Western mainstream. He was a polymath and practitioner who treasured an ancient way of life, and whose thought was refined by his scientific training and experience in both Soviet and post-Soviet life.

[1] Emil Shukurov, Sochineniia (Bishkek, 2007).

[2] Emil Shukurov, “Ustoichivoe razvitie v Tsentral’noi Azii: tochki prilozheniia sil,” Biom ekologicheskoie dvizhenie, 2015, http://www.biom.kg/teachers/5805f823744777dd5e3933a5.

[3] Oksana Tarnetskaia, “Vspominaia Emilia Shukurova,” Liven’: Living Asia, January 19, 2020, accessed August 10, 2021, https://livingasia.online/2020/01/19/vspominaya-emilya-shukurova-2/.

[4] “Molchanie slov: Shtrikhi k portretu E. Dzh. Shukurova,” documentary film produced by Taalim-Forum, 22:47, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JWM3cP7DcsU.

[5] Taailm-Forum, accessed August 11, 2021, http://www.taalimforum.kg/index.php/en/.