By Victoria Kim

Victoria Kim holds an MA from the Johns Hopkins University’s SAIS in Korean Studies and MA from the University of Bolton in International Multimedia Journalism. Originally from Tashkent, Uzbekistan, she is currently based in Beijing, China, as a researcher and documentary storyteller. Her multimedia long-reads and podcasts on the Korean diasporas in the former Soviet Union and Latin America are featured in The Diplomat and by the Korea Economic Institute of America. Victoria is also a speaker on the topics to international audiences at the George Washington and Johns Hopkins Universities in Washington DC, University of Missouri, Royal Asiatic Society and World Culture Open in China and South Korea.

Victoria Kim holds an MA from the Johns Hopkins University’s SAIS in Korean Studies and MA from the University of Bolton in International Multimedia Journalism. Originally from Tashkent, Uzbekistan, she is currently based in Beijing, China, as a researcher and documentary storyteller. Her multimedia long-reads and podcasts on the Korean diasporas in the former Soviet Union and Latin America are featured in The Diplomat and by the Korea Economic Institute of America. Victoria is also a speaker on the topics to international audiences at the George Washington and Johns Hopkins Universities in Washington DC, University of Missouri, Royal Asiatic Society and World Culture Open in China and South Korea.

May 4, 2021, marked the 116th anniversary of the arrival of ethnic Koreans in Latin America. The historical, economic, and political parallels between the experiences of the Korean diasporas in Latin America and Eurasia have helped inform South Korea’s successful foreign policies toward both regions over the past two decades.

These efforts have been spearheaded by South Korea’s past four presidents. Indeed, if the country’s public diplomacy had been directed toward its rise as a “middle power” player in the Asia-Pacific region even before Roh Moo-hyun took office in 2003, only in 2008, under Lee Myung-bak’s administration, did the term junggyunguk, or “middle country,” officially enter South Korean political circles and the country’s foreign policy.

Over the last two decades, the country has managed to reconnect not only with the half-a-million people strong post-Soviet Korean diaspora, known as Koryo Saram, but also with the tens of thousands of ethnic Koreans scattered across Latin America, from their original point of disembarkation on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula to Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and beyond.

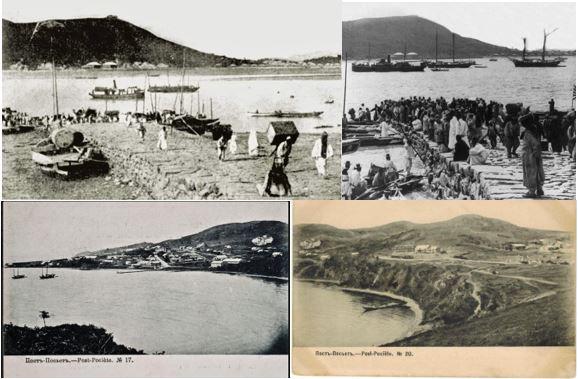

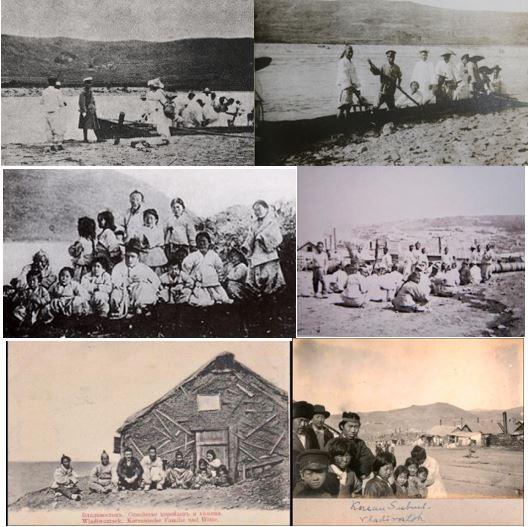

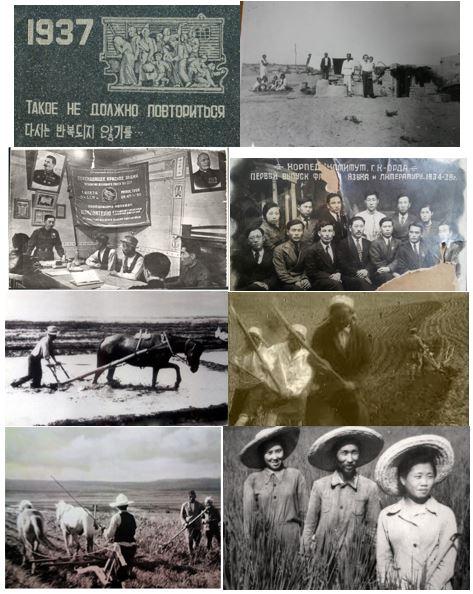

Figure 1. Ports of Chemulpo (present-day Incheon) in Mexico (top row) and Posyet in the Russian Far East (bottom row) in 1903-1905, in the midst of two waves of Korean global migration by sea and by land

Source: Koryo Saram: Memory in Faces, https://www.facebook.com/pamyatvlitsah/photos

The pragmatism with which South Korea has navigated the sometimes murky waters of its cultural and ethnic relations with its global diaspora is truly fascinating. Behind the rhetoric of restoring the quasi-lost linguistic and cultural heritage of isolated overseas Koreans who long to be nurtured in the caring—and now rich and prosperous—cradle of their historical Motherland lies decades of insatiable South Korean demand for natural energy, as well as a search for alternative geopolitical energy routes and ways to diversify its over 80% energy-deficient market’s heavy dependence on the Middle East.

In addition, the highly sophisticated and export-oriented South Korean capitalist system—based in recent history on state-led and chaebols-backed economic and political growth—has been on the constant look-out for new markets to complement its existing regional and global trade relationships. Incidentally, the countries of Eurasia and Latin America that are home to strong Korean diasporas have developing markets that are abundant in energy and other natural resources—and thus highly complementary with that of South Korea.

From the Korean Diaspora in Latin America…

In early April 1905, the first 1,033 Korean labor migrants to Latin America boarded a British cargo ship in the Korean port of Chemulpo (now Incheon), won over by promises of stable work and regularly paid wages in distant Mexico at a time of increasing tumult on the Korean peninsula.

At the end of that year, Japan won the Russo-Japanese War, becoming the first Asian empire to defeat a Western one. As a result, Korea became a Japanese protectorate. The country would be officially annexed and colonized five years later, in 1910, ceasing to be an independent kingdom. This foreshadowed Japan’s further colonization of North-East Asia during the first half of the twentieth century.

Earlier, in January 1903, the first shipload of Koreans had arrived on the American island of Hawaii to work on pineapple and sugar plantations. By 1905, over 7,000 Korean labor migrants had made the voyage from Chemulpo to the US to work as low-paid contractors.

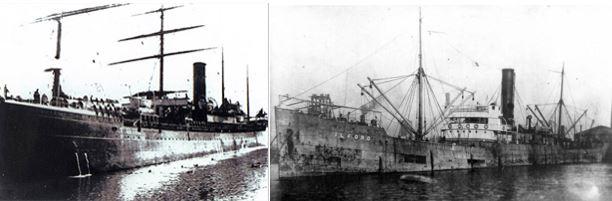

Figure 2. The British cargo ships S.S. Gaelic (left) and S.S. Ilford (right), which took the first 100 Korean labor migrants to Hawaii at the end of 1902 and over 1,000 to Mexico on April 4, 1905

Source: Koryo Saram: Memory in Faces. //www.facebook.com/pamyatvlitsah/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

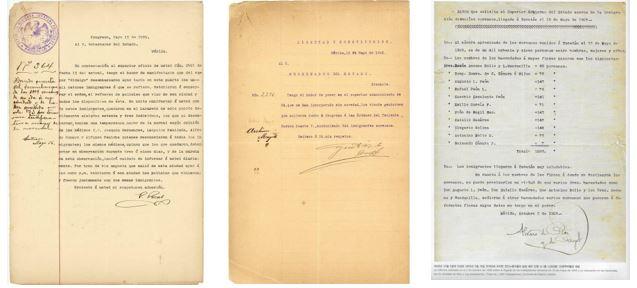

After a month-long journey, on May 14, 1905, over 1,000[1] Koreans finally arrived at the Mexican port of Progreso near Merida on the Yucatan peninsula. Having been lured by British promises of four- or five-year contracts for paid employment, these laborers soon found themselves in conditions of practical slavery. Upon arrival, they were effectively sold to 22 local land and plantation owners to work for free on the henequen plantations of Yucatan alongside the local Yaqui and other indigenous groups. The history of Korean immigration to Mexico thus began with sweat and blood.

Figure 3. Arrival of the first Korean immigrants at the Mexican port of Progreso on the Yucatan Peninsula in mid-May 1905

Source: Koryo Saram: Memory in Faces, https://www.facebook.com/pamyatvlitsah/photos

Cutting henequen to produce a jute-like fiber—a material in high demand throughout the first half of the twentieth century due to the First and Second World Wars—was excruciatingly painful, as the plants were literally covered in thorns.

In 1910, the exhausted unpaid Koreans in Mexico would experience a new type of suffering. With the formal annexation of Korea to Japan, they lost their status as citizens of Korea. Yet despite the strenuous efforts of the Japanese empire to claim sovereignty over its new Korean “subjects” in Mexico, most of them refused to accept Japanese citizenship.

Figure 4. Documents confirming the arrival of ethnic Koreans at the port of Progreso on May 14, 1905 (left) and Merida on May 15, 1905 (right). The third document (bottom), signed on October 2, 1908, confirms their “passage” to plantation owners in Merida on May 15, 1905.

Source: Koryo Saram: Memory in Faces. //www.facebook.com/pamyatvlitsah/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

In the face of the dire situation in Mexico, some Koreans tried to escape to Hawaii via San Francisco, California, but without success. Around 1921, when the demand for henequen fiber suddenly started declining, 288 Korean laborers finally managed to escape to Cuba from the Mexican port of San Francisco de Campeche. To this day, the one-thousand-strong Korean diaspora in Cuba acknowledges the “300 Mexican Korean Spartans” as its official forebears.

With the passage of time, the remaining descendants of those unfortunate Korean slave workers in Mexico managed not only to survive, but also to integrate themselves into local society and start new lives—mostly in bigger cities—in the country that had so unwillingly accepted them. Thus did the Korean story become part of the complicated Mexican history, with all its own post-revolutionary turmoil of the early twentieth century.

Figure 5. Visual evolution of the first Mexican Koreans from slave laborers on henequen haciendas to full-fledged Mexican citizens (portrayed through archival photographs)

Source: Koryo Saram: Memory in Faces. //www.facebook.com/pamyatvlitsah/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

Until very recently, the approximately 20,000 ethnic Koreans living in Mexico were not integrated into the South Korean foreign policy framework due to their geopolitical isolation and disconnection from the post-colonial Republic of Korea.

In the early 1960s, however, South Korea established diplomatic relations with every country in Latin America except Cuba. At that time, the Latin American region was welcoming migrant workers to help support its industrial development. Korea, plagued as it was by socio-political and economic instability and over 8% unemployment, therefore promoted emigration to Latin America via the Overseas Emigration Act (Act 1030)[2] with the goals of “efficient population policy, economic stability and enhancement of national prestige.”[3]

The first emigrants under this scheme—a group of roughly 100 Koreans—left for Brazil in December 1962. Since then, tens of thousands of ethnic Koreans have emigrated to Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Peru, and Chile. An estimated 100,000 Korean immigrants and their descendants now live in Latin America.[4]

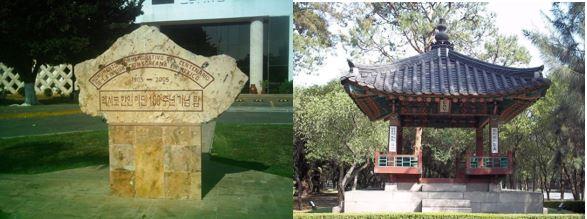

Figure 6. Monument in Merida commemorating the 100th anniversary of the first Koreans’ arrival in Mexico (left) and the Korean friendship pavilion in Mexico City (right)

Sources: “Mexico-South Korea Relations,” Wikipedia, accessed September 9, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexico%E2%80%93South_Korea_relations; “Koreans in Mexico,” Wikipedia, accessed September 9, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koreans_in_Mexico.

The second wave of Korean labor migration to Mexico was unleashed in the 1970s-1980s, when South Koreans as well as Argentine and Paraguayan Koreans (together with other Paraguayan and Argentine labor migrants) arrived in prosperous Mexico from their much more embattled economies, looking for jobs, better opportunities, and improved living conditions.

As of the end of the 1990s, there were almost 20,000 ethnic Koreans living in Mexico alone. These numbers have fluctuated over time, from 15,000 in the early 2000s to 12,000 in 2013, according to the New York Times. Most recently, the Mexico City Association of Korean Descendants claimed in mid-March 2021 that around 30,000 Koreans resided in various Mexican states, from Baja California and Baja California Sur to Tlaxcala, Puebla, Yucatan Peninsula, and Mexico City.

However, it is only since the early 2000s that the Mexican Korean diaspora has really reached a certain degree of recognition. This is due to South Korea’s blend of public diplomacy and ethno-cultural soft power there, which has occurred in parallel with diasporal outreach in Latin America (Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Peru) as well as across Eurasia.

This foreign policy model has solidified South Korea’s international status as a “middle power” in the increasingly multipolar global economic and political system and helped to build lasting and functional social and human networks in the regions and countries that received two major waves of ethnic Korean migration—by sea and by land—during the most tumultuous epoch in the history of the Korean Peninsula, namely the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Figure 7. The national Day of the Korean Immigrant in Mexico was first celebrated on May 4, 2019, as Korea Day in Yucatan and Campeche (where it retains that name)

Sources : Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021).

…to the Korean Diaspora in Central Asia

Figure 8. Descendants of ethnic Korean deportees in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan (top row) and Korean labor migrants in Yucatan and Campeche in Mexico (bottom row), all dressed in festive South Korean dress, waving and pledging allegiance to the South Korean national flag alongside their local flags

Sources: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah. //www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

The authoritarian post-Soviet economies in transition and the emerging markets of Latin America represent ideal trade partners for the Republic of Korea. Both regions enjoy abundant natural energy and other resources that can be exported to South Korea, which lacks such resources, in exchange for manufactured goods, machinery, hardware, and software.

Moreover, as a true “middle power”[5] caught between the political and economic interests and influences of Japan and China in one region and China and the United States in the other, developing bilateral ties and agreements and establishing free trade and travel zones in Eurasia and Latin America has been the constant goal of the past four South Korean presidential administrations.

To further analyze South Korea’s masterful foreign policy and public diplomacy in Latin America and Eurasia, which is based on diasporal outreach and ethno-cultural soft power politics,[6] let us turn to regional economic statistics and the record of South Korean presidential, diplomatic, and cultural exchanges and state visits over the past two decades.

As we can see from Table 1 in Appendix, there are many similarities between South Korea’s bilateral economic, political, and cultural interactions with its trading partners in Latin America and those with its partners in Eurasia.

Mexico and “Russia plus Central Asia” are South Korea’s number-one partners in terms of bilateral trade in the two regions, with a trade volume of over US$21 billion with Mexico, over US$22 billion with Russia, and over US$15 billion with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan combined. Moreover, South Korean foreign direct investments in Central Asia’s two top economies and in the Mexican economy both equal over US$7 billion, while those in the Russian economy exceed US$4 billion.

In addition to their high degree of trade complementarity with South Korea, these countries host significant numbers of ethnic Koreans: tens of thousands of descendants of former slave laborers in Mexico and hundreds of thousands of former political deportees and their descendants in Central Asia and Russia.

Figure 9. Ethnic Korean descendants in Mexico on Korea Day on May 4, 2019 (top row), in Kazakhstan in September 2019 at the unveiling of Monument of Gratitude to the Kazakh People (middle row) and in Uzbekistan in April 2019 during the ceremonial opening of the Korean Culture and Art Palace (bottom row)

Sources: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah, www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); “Ne tol’ko politika: fotoitogi visita glavi Korei v Uzbekistan”, SPUTNIK Uzbekistan, uz.sputniknews.ru/20190422/Politika-i-ne-tolko-fotoitogi-vizita-glavy-Korei-v-Uzbekistan-11306378.html (accessed October 4, 2021); “V parke Karagandi poyavilsya pamyatniy znak blagodarnosti koreyskogo naroda”, eKaraganda. //ekaraganda.kz/?mod=news_read&id=89063&fbclid=IwAR0LxacqjvNYdakcNlZq9Cj23V-BK-PhO1LMbJOGO4XSAD4TPO1_mfvuPaM (accessed October 4, 2021)

Most interestingly, South Korea appears to employ a similar mixture of foreign policy and diplomacy in both Latin America and Eurasia, including very successful ethno-cultural soft power[7] and diasporal outreach in the main economic players in both regions. In both regions, it seeks to transform ethnic Korean diasporas—who are the descendants of the original migrations—into pro-South Korean political and economic (rather than purely cultural) actors, as part of its struggle as a middle power to penetrate as deeply as possible these very economically appealing markets and gain political influence.

South Korea is aided in these efforts by certain very influential members of ethno-cultural Korean societies in Mexico and the former USSR who coincidentally”form part of the local governments in these countries. The latter, who benefit economically and politically from so-called South Korean “cultural” financial aid, actively promote South Korea’s economic, social, and political agenda under the banner of mutual cultural cooperation.

Figure 10. The first Korea Day in Mexico on May 4, 2019, with celebrations in Yucatan and Campeche. The mayors of Merida (now a twin city of Incheon/Chemulpo), San Francisco de Campeche, and Progreso were present at all festivities, as was then-South Korean ambassador Kim Sang-il.

Sources : Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México. www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche. //www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba. //www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México. //www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

For instance, the head of the South Korea–Mexico Friendship Society, David Bautista Rivera Morena, is also a deputy in the Mexican Congress. Following his introduction of an official initiative, the Mexican chamber of deputies on March 18, 2021, approved the Day of the Korean Immigrant on May 4 as a national holiday by a vote of 384 votes to 12 (with 55 abstentions). This holiday was subsequently added to the civil calendar.

Such formal recognition of the importance of its diaspora’s immigration to the recipient country has not been achieved by any other Asian diaspora in Mexico—including those with a longer history of migration there, such as the Chinese and Japanese diasporas—nor by any other Korean diaspora globally. It is a testament to the success of the efforts of the Korean diaspora in Mexico, as well as the direct diplomatic efforts of the South Korean government and its embassy in the country.

Not only does the holiday reflect Mexicans’ respect for the right to immigrate and the historical importance of ethnic Korean immigration to Mexico, but it also builds on the Day of Korea originally celebrated in the states of Yucatan and Campeche on the same day in 2019. That holiday came into being following a decision by the local congress, which was lobbied by the South Korean embassy—led by its then-ambassador, Kim Sang-il—to mark the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the provisional Korean government in Mexico during the Korean independence movement that began on March 1, 1919.

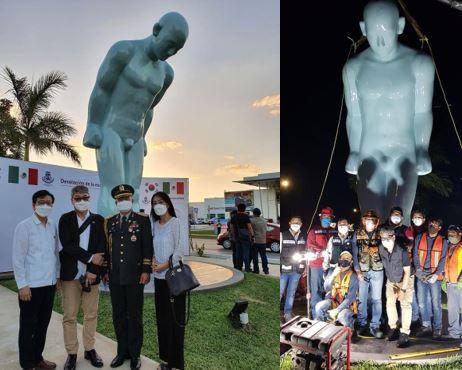

Figure 11. Greetingman’s official unveiling on Republic of Korea Avenue in Merida on the Yucatan Peninsula in mid-March 2021, attended by current South Korean ambassador Suh Jeong-in and its South Korean creator, Yoo Yong-ho

Sources: Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

On March 17, 2021, the day before the Mexican government voted to adopt the new national holiday commemorating Korean immigration to Mexico, the statue of Greetingman, or El hombre que saluda, created by South Korean sculptor Yoo Yong-ho in 2020 to commemorate the 115th anniversary of the departure of Korean labor migrants to Mexico, was installed on the Avenue of the Republic of Korea in Merida. The avenue itself was renamed thus in December 2017 after the efforts of then-South Korean ambassador Chun Bee-ho to celebrate the 55th anniversary of the establishment of a diplomatic relationship between South Korea and Mexico culminated in the successful signing of agreements to change its name. The installation features a 6-meter-tall turquoise figure of a nude male inclined in a traditional 25-degree kneeling posture recognizable as Korean and symbolic of the “beginning of any cordial relationship,” according to the plaque that appears at the base of the statue.

Similarly, the Korea-Mexico Friendship Hospital was opened in Merida in 2005 following Roh Moo-hyun’s presidential visit to Mexico in that year. It has received regular donations from the South Korean government ever since, including US$200,000 in 2016 under Chun Bee-ho’s patronage. Its pediatric ward was expanded in 2015 to enable it to serve a total of 54,000 minors. The Samsung plant in Queretaro made another donation in 2019, during Kim Sang-il’s tenure.

Each of these events were linked to an anniversary of the arrival of the first ethnic Koreans in Mexico in 1905. Merida, whereto the first Korean immigrants (slave laborers) initially arrived in Mexico, and Incheon, wherefrom Korean labor migrants departed to Hawaii and Mexico at the beginning of the 1900s, even became official twin cities in 2007.

Figure 12. Renaming of a street in Merida as Republic of Korea avenue in December 2017 (top row) and opening of the Korea-Mexico Friendship Hospital in 2005 and the US$200,000 donation in 2016 (bottom row). Pictured is then-South Korean ambassador Chun Bee-ho.

Sources: “Nombran República de Corea a avenida en Altabrisa”, La Jornada Maya, www.lajornadamaya.mx/yucatan/136731/nombran-republica-de-corea-a-avenida-en-altabrisa (accessed October 4, 2021); “Fortalecen capacidad de atención del Hospital de la Amistad Corea-México”, La Revista Peninsular, www.larevista.com.mx/yucatan/fortalecen-capacidad-de-atencion-del-hospital-de-la-amistad-corea-mexico-1925 (accessed October 4, 2021)

Figure 13. Mexican Korean descendants pledging allegiance to the South Korean national flag and making a fashionable South Korean pop culture symbol for “love”

Sources: Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

Lessons Learned from the Korean Diasporas in Central Asia and Russia

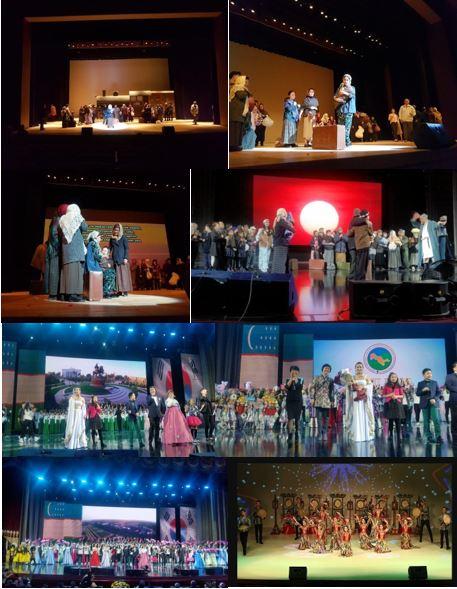

The year 2017 marked the 80th anniversary of the Korean deportation to Central Asia, the first deportation of an entire ethnicity in the Soviet Union. This solemn event was widely commemorated across Eurasia and in South Korea by major academic conferences, official state events, and even plays and concerts.

What undeniably set these commemorations apart from earlier ones—which had framed the 1937 deportations as a criminal act on the part of the Soviet state—was the celebratory tone of most events. Russian, Central Asian, and even South Korean academics and politicians sought to rewrite history, turning the focus away from the human rights abuses perpetrated by the Soviet (now Russian) state, which deported Koreans for political purposes, and toward the benevolent responses of those Central Asians who received the deported people.

Figure 14. Scenes from the theater performance “Uzbekistan Is Our Home” in Tashkent in November 2017 at the concert for the 80th anniversary of the 1937 “forced resettlement” of ethnic Koreans and from Moon Jae-in’s official presidential visit to Uzbekistan in April 2019

Sources: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah. //www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); “Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Moon Jae-in open House of Korean Culture and Art in Tashkent”, Kun.uz. //kun.uz/en/news/2019/04/20/shavkat-mirziyoyev-moon-jae-in-open-house-of-korean-culture-and-art-in-tashkent (accessed October 4, 2021)

The story that the friendly residents of the Central Asian republics greeted the exhausted deportees warmly and shared everything they had with the displaced Koreans, in the best tradition of the “friendship of nations” ideology that prevailed in the USSR during that era, was repeated in official speeches and commemorative events across Russia, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan—and even in South Korea. It was even reflected in the final gestures of recognition unveiled the same year or shortly thereafter by the grateful Korean diasporas in the recipient countries. South Korean government and diplomatic representatives were heavily involved in the latter events, not least because the 80th anniversary of the 1937 deportation coincided with the 25th anniversary of diplomatic relations between South Korea, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan in 1992, a far more significant anniversary from their perspective.

Similarly to Mexico’s Greetingman, a monument dedicated to the friendship of the Korean and Uzbek peoples was officially inaugurated in Tashkent in early July 2017 during the visit of then-mayor of Seoul Park Won-soon to Uzbekistan (which occurred simultaneously with Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s official visit to South Korea). It was formally unveiled in the Friendship Garden in front of Seoul Park, the only park in Uzbekistan administered by South Korean government funding. The park, which opened in 2010, was a gift from the Seoul’s mayor office when Tashkent and Seoul became official twin cities following Lee Myung-bak’s presidential visit to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan in 2009.

Figure 15. Unveiling of the Korean-Uzbek People’s Friendship Monument in the Friendship Garden of Seoul Park in Tashkent in July 2017, in the presence of the mayors of the twin cities Tashkent and Seoul

Sources: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah, www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); “Monument commemorates Korean diaspora in Uzbekistan”, Korea.net, www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Society/view?articleId=147727 (accessed October 4, 2021)

Over the course of the past four South Korean presidential regimes, the name of the strategy may have changed—from Comprehensive Central Asia to New Asia to Eurasia Initiative—but the strategy itself has remained intact: to strengthen as much as possible bilateral political and economic relations with Central Asia and Russia. This is very similar to the goal of the South Korean strategic partnership with Mexico in Latin America.

The Central Asian region—rich in the natural resources vital to the energy-deficient South Korean market—has even earned itself a new nickname that appears on the Republic of Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ official website: “another Middle East.”

Figure 16. Moon Jae-in’s virtual greeting to Uzbekistani Korean compatriots during the “Uzbekistan Is Our Home” concert in Tashkent in November 2017 commemorating the 80th anniversary of the 1937 “forced resettlement” and his participation in a similar concert during his presidential visit to Uzbekistan in April 2019

Sources: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah, www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); “Ne tol’ko politika: fotoitogi visita glavi Korei v Uzbekistan”, SPUTNIK Uzbekistan, uz.sputniknews.ru/20190422/Politika-i-ne-tolko-fotoitogi-vizita-glavy-Korei-v-Uzbekistan-11306378.html (accessed October 4, 2021)

In 2019, two other important events happened in parallel in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, coinciding with Moon Jae-in’s first presidential visit to those countries in April. In Tashkent, a pompous House of Korean Culture and Art was officially unveiled by the presidents of South Korea and Uzbekistan, while in Kazakhstan another Monument of Gratitude to Kazakhs from the Korean people was opened in Karaganda’s Central Park in September, upon the 30th anniversary of the city’s Korean ethno-cultural center.

Figure 17. Monument of Gratitude to the Kazakh People, opened by Kazakhstani Koreans in Karaganda in September 2019, and the official unveiling of the Korean Culture and Art Palace in Uzbekistan in April 2019 by the South Korean and Uzbek presidents, Moon Jae-in and Shavkat Mirziyoyev

Sources : Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah, www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); “Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Moon Jae-in open House of Korean Culture and Art in Tashkent”, Kun.uz, kun.uz/en/news/2019/04/20/shavkat-mirziyoyev-moon-jae-in-open-house-of-korean-culture-and-art-in-tashkent (accessed October 4, 2021);“V parke Karagandi poyavilsya pamyatniy znak blagodarnosti koreyskogo naroda”, eKaraganda, ekaraganda.kz/?mod=news_read&id=89063&fbclid=IwAR0LxacqjvNYdakcNlZq9Cj23V-BK-PhO1LMbJOGO4XSAD4TPO1_mfvuPaM (accessed October 4, 2021)

While the event in Kazakhstan had significant local flair, the same could not be said about Uzbekistan’s unveiling of the Monument of Korean and Uzbek People’s Friendship in 2017 or opening of the Korean Culture and Art House in 2019. The idea of building a house of Korean culture in Uzbekistan was born as early as 2014, during Park Geun-hye’s visit to Uzbekistan, which featured meetings with then-president Islam Karimov. But this, like all the other activities, events, and projects brought to fruition by the Korean diaspora in Uzbekistan over the past decade, was masterminded by one key figure: Uzbek Supreme Council deputy and head of the Association of Korean Cultural Centers in Uzbekistan Victor Park.

Like the head of the Mexico-Korea Friendship Association, who is also an official member of the Mexican Congress, Victor Park is an official member of the Uzbek government who works hard to promote South Korean interests from within. He also enjoys direct access to funding from the Republic of Korea’s ODA (Official Development Assistance) and the Overseas Koreans Foundation—some of which was added to Uzbek public funding to open the aforementioned Palace of Korean Culture and Art (not without a local corruption scandal in the process of its construction). Park “coincidentally” received two medals in 2014 when then-South Korean president Park Geun-hye visited Uzbekistan for the first time: the Friendship one from Islam Karimov and the Camelia one from Park Geun-hye herself.

Figure 18. Victor Park, chairman of Uzbekistan’s Association of Korean Cultural Centers and Uzbek Supreme Council deputy, as a key figure at all major Uzbekistani Korean festivities, including the unveiling of the People’s Friendship Monument in Tashkent’s Seoul Park in July 2017 and the presidential opening of the Korean Culture and Art Palace in April 2019

Sources: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah, www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); “Ne tol’ko politika: fotoitogi visita glavi Korei v Uzbekistan”, SPUTNIK Uzbekistan, uz.sputniknews.ru/20190422/Politika-i-ne-tolko-fotoitogi-vizita-glavy-Korei-v-Uzbekistan-11306378.html (accessed October 4, 2021)

A similar situation prevails in Russia, where all key members of the Joint Russian Union of Koreans—the organization that officially represents the interests of the Korean diaspora in the Russian Federation—are also active members of the Russian government and have received a slew of medals. The organization’s head, Vasiliy Tso—a former USSR Supreme Council deputy and a current member of the Russian Federation’s Presidential Council on international relations—has been awarded three such medals:

- The “People. Constitution. President” medal, awarded in 2003 by then-South Korean president Roh Moo-hyun, who had only recently taken office at the time;

- The Friendship medal, awarded by Vladimir Putin on the occasion of Roh Moo-hyun’s 2004 visit to Russia; and

- The Honor medal, awarded by Vladimir Putin on the occasion of Moon Jae-in’s 2017 visit to Russia.

Figure 19. Joint Russian Union of Koreans chairman Vasiliy Tso and head of the Far Eastern Korean Organizations’ Association Valentin Park receive the presidential medals of Honor and Friendship (in 2004 and 2017 during South Korean presidential visits to Russia and in March 2021 during the official celebration of the 30th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Russia and South Korea in 2020, respectively)

Sources: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah. //www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); “Putin nagradil Valentina Paka ordenom Druzhbi”, Konkurent. //konkurent.ru/article/37299 (accessed October 4, 2021)

Two of his three vice-presidents have also been awarded Russian presidential medals: Oleg Tsoi is a Hero of the Russian Federation and German Tsoi received the Friendship medal in 2007. Finally, Valentin Park, the head of the Far Eastern Korean Organizations’ Association—the Far East being where ethnic Koreans were deported from in 1937—was awarded the Friendship medal in March 2021.

Park also unveiled a monument in Vladivostok on the 150th anniversary of the Friendship of Russian and Korean People in 2015 (the first monument of its kind in Russia), in which year he was awarded the state medal “For good deeds.”

Figure 20. Scenes from the concerts in the Far East in September 2017 and in Uzbekistan in November 2017 marking the 80th anniversary of the 1937 “forced resettlement” of Koreans. Representatives of the Russian Korean diaspora donated a depiction of the Korean deportees in winter 1937 to their Uzbek Korean peers.

Source: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah. //www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021)

March 2021 witnessed the celebration of the 30th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Korea in 2020. Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov finally visited South Korea—his visit and the corresponding festivities having been postponed by a year due to the Covid-19 pandemic—and the Year of Mutual Exchange was officially proclaimed.

Over the last 30 years, the trade volume between South Korea and Russia has grown from US$190 million to US$22 billion but the two countries have been closely politically and culturally intertwined since the early 1860s, when ethnic Koreans from the north of the Korean peninsula started migrating to the then-newly acquired Russian territories of outer Manchuria in Primorskii Kraiunder the 1858-1860 Beijing treaty with Qing China.

Figure 21. Presidential visits of Lee Myung-bak and Moon Jae-in to the Russian Federation (2008, 2017, and 2018); Moon Jae-in became in 2018 the first foreign leader to speak to the Russian parliament. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov visited Seoul in March 2021 to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Russia and South Korea.

Sources: “Russia-South Korea relations”, Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russia%E2%80%93South_Korea_relations (accessed October 4, 2021);“S.Korea, Russia mark 30 years of diplomatic ties”, KBS World, world.kbs.co.kr/service/news_view.htm?lang=e&Seq_Code=160375 (accessed October 4, 2021)

In the early 1900s, following Japan’s colonization of Korea in 1905-1910 and severe suppression of the March 1 independence movement of 1919, the numbers of Koreans flocking to the neighboring Russian Far East to escape, rebel, and find ways to defeat the imperial aggressor and regain their homeland’s independence quadrupled from 12,000 people in the late 1860s to 30,000 by the late 1920s and over 170,000 by the late 1930s.

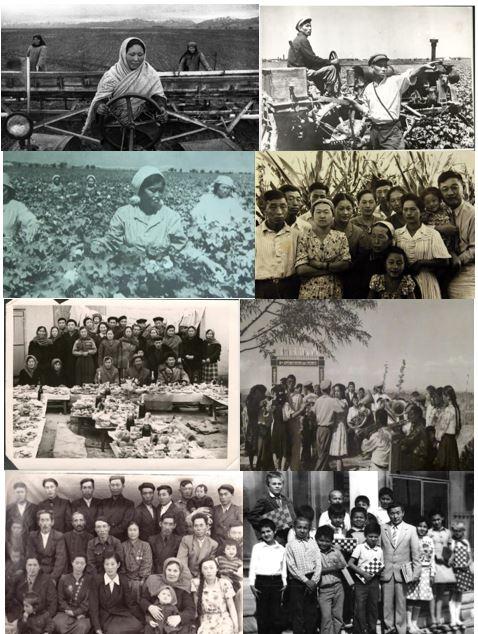

It was then, in the late summer and early fall of 1937, that ethnic Koreans were rounded up and deported under Joseph Stalin’s decree No. 1428-326сс to Central Asia, with its sands, swamps, and steppes. The official justification for this wholesale deportation of ethnic Koreans—which occurred in a matter of months, if not weeks—was that they were all “enemies of the state.” In reality, the Soviet state’s concern was the growing aspirations of ethnic Koreans in the late 1920s to unite the Far Eastern territories into an autonomous Korean national district—a project similar to the Jewish and German autonomous regions and republics, which also fared badly under Stalin’s repressions of ethnic minorities in the 1930s and 1940s.

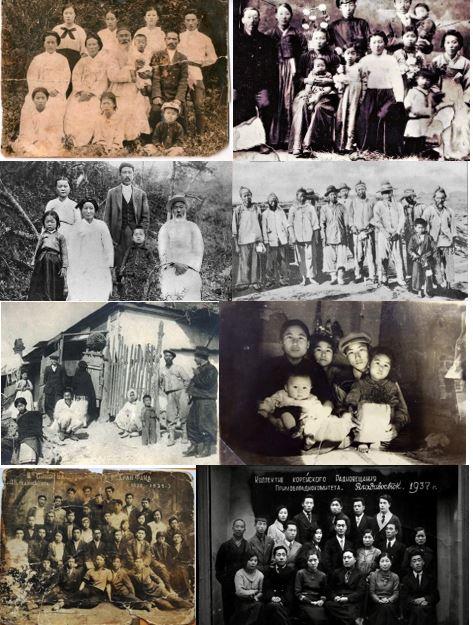

Figure 22. Visual chronology of Koryo Saram’s recent history (1860s-1960s) through archival documentary photography

Source: Koryo Saram: Memory in Faces. //www.facebook.com/pamyatvlitsah/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

Consequently, the dream of a semi-independent autonomous Korean national district in the Far East was never realized. However, the deportations sowed the seeds for the current diplomatic relationships between South Korea and the Central Asian states, as they led to the first encounters between Kazakhs and Uzbeks—and later Kyrgyz, Tajiks, and Turkmen—with the 172,000 Korean deportees. Despite their own dire poverty, local Central Asian communities shared their scarce food and precarious shelter with these strangers who had even less than they did.

Figure 23. South Korean presidential visits to Central Asia and meetings with Central Asian leaders over the last 20 years

Sources: “Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Moon Jae-in open House of Korean Culture and Art in Tashkent”, Kun.uz, kun.uz/en/news/2019/04/20/shavkat-mirziyoyev-moon-jae-in-open-house-of-korean-culture-and-art-in-tashkent (accessed October 4, 2021); “List of international presidential trips made by Moon Jae-in”, Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_international_presidential_trips_made_by_Moon_Jae-in (accessed October 4, 2021); “Kim Dae-jung”, Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kim_Dae-jung (accessed October 4, 2021); “Roh Moo-hyun”, Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roh_Moo-hyun (accessed October 4, 2021); “Park Geun-hye”, Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Park_Geun-hye (accessed October 4, 2021); “Moon Jae-in”, Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moon_Jae-in (accessed October 4, 2021)

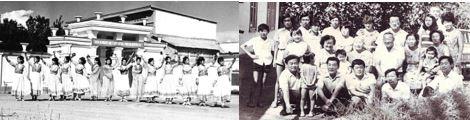

The Koreans soon returned the favor. They dried up the swamps and developed the steppes into arable lands on which they grew new kinds of wheat and rice from the grains they had brought with them from the Far East in 1937. They also produced record amounts of jute, for which they were highly praised by the Soviet leadership and awarded numerous medals and prizes throughout the Second World War. With the death of Joseph Stalin, their “illegal” status was slowly shed, allowing Central Asian Koreans to integrate themselves into local societies while retaining only the memories of past repressions, persecutions, and hardships.

Over the past two decades, South Korea has masterfully navigated its sometimes uneasy cultural and ethnic relationships with members of the global Korean diaspora in Latin America and Eurasia. Exploitation of its soft power in these regions has allowed the country to cement its status as a “middle power.”[8] by boosting its political and economic engagement with the independent states of Russia and Central Asia as well as the relatively recently liberalized Mexican and other Latin American markets.

Figure 24. Besides her involvement in corruption scandals—which sent shockwaves through South Korea and led to her impeachment in 2017 and 24-year imprisonment in 2018—ex-president Park Geun-hye will be remembered worldwide for the success of her so-called “cultural soft power diplomacy.” She is pictured here with the presidents of Uzbekistan and Mexico in 2014 and 2016 and during her visit to Iran in 2016.

Sources: “Park Geun-hye”, Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Park_Geun-hye (accessed October 4, 2021); “K-Culture Diplomacy: From São Paulo to Tehran”, The Diplomat, thediplomat.com/2016/05/k-culture-diplomacy-from-sao-paulo-to-tehran/ (accessed October 4, 2021); “Два президента открыли Дом корейской культуры. Его застройщик обвинил Ташкент в жульничестве”, Радио Озодлик, rus.ozodlik.org/a/29893159.html (accessed October 4, 2021).

What will likely follow from these efforts will be the signing of new free trade agreements with Mexico—where the talks, which reached a stalemate after Lee Myung-bak’s presidential visit in 2012, were revived by then-South Korean president Park Geun-hye on a “cultural diplomacy” visit to Mexico in 2016 shortly before she was ousted from the office and jailed on charges of corruption in 2017—and with Uzbekistan, where negotiations started in 2019 following the visit of incumbent South Korean president Moon Jae-in and have been in active discussion since January 2021.

This will mark the culmination of a successful South Korean foreign policy that has seen the country strengthen its economic ties with most of Eurasia and Latin America over the last 20 years. Bilateral and regional FTAs have existed with Russia since 2018; South Korea has also been in active negotiations with the Eurasian Economic Union (Russia, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Belarus, and Kyrgyzstan) since then-Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev’s visit to Seoul in 2016. In Latin America, South Korea has signed and ratified active FTAs with Chile, Colombia, and Peru and is planning to do so with the rest of Central America (Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama and Guatemala) and MERCOSUR (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay) besides Mexico.

Figure 25. Unveiling of memorial plates installed next to the Greetingman in Merida (top row, left) and Port of Progreso (top row, right) to commemorate the 115-year-long friendship between Mexico and Korea and the arrival of the first Korean labor migrants to the Port of Progreso on May 14, 1905[9]

Sources: Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

At the cultural level, South Korean ambassador to Mexico Suh Jeong-in has been working to strengthen the ties between the two countries. Following the erection of Greetingman on the Avenue of the Republic of Korea in Merida in mid-March 2021 and the addition of a plate commemorating the arrival of 1,019 Korean labor migrants at the port of Progreso on the Yucatan Peninsula, he commenced a search for surviving Mexican veterans of the Korean War, which began over 70 years ago and in which three million civilians and one million active military personnel lost their lives. Interestingly, Mexico never participated in that war: as it was a neutral country, the only way Mexican nationals could really take part in such military actions was by enlisting in the U.S. Army.

Another initiative is an ongoing search for the descendants of the Korean patriots and independence fighters who contributed to the March 1, 1919, movement and the liberation of Korea.

Figure 26. Promotional poster about the South Korean embassy in Mexico’s search for the surviving Mexican veterans of the Korean War (left) and the April 2021 award ceremony for Mexican Korean descendants of those who contributed to the March 1, 1919, Korean independence movement (right)

Sources: Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

Meanwhile, with the first nationwide celebrations of May 4 as the Day of the Korean Immigrant, Mexican newspapers began to spread a narrative about Koreans who fled their country in the face of Japanese takeover 116 years earlier and found refuge—and a more prosperous future for their children—in Mexico, which purportedly welcomed them with open arms.

This sounds eerily similar to official rhetoric about the 1937 deportation of ethnic Koreans in the former Soviet Union, which holds that friendly Russians, Kazakhs, and Uzbeks embraced the deported Koreans—who had been deprived of everything, including their own nationality—after they were sent to the ends of the earth.

Figure 27. Day of Korean Immigrant in Mexico—still celebrated in Yucatan and Campeche as Korea Day—on May 4, 2021, featuring the biggest bibimbab (sponsored by the Overseas Koreans Foundation and Hyundai, among others), Korean traditional hangul calligraphy contest, etc.

Sources: Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

What both narratives neglect to mention—whether intentionally or not—are the political, social, physical, and moral crimes against humanity that were committed against Koreans, both as slaves on the Yucatan Peninsula in 1905 and deportees to Central Asia in 1937. Emblematically, official statements and even publications by major post-Soviet historians and academics have widely substituted the more politically correct and milder-sounding term “forced resettlement” for “deportation.”

Figure 28. South Korean K-pop dominated the scene at events commemorating the arrival of ethnic Korean labor migrants to Mexico in 1905 (scenes from the event in Campeche on May 4, 2021, which featured a local female K-pop band) and deportees to Central Asia in 1937 (scenes from the concert in Uzbekistan in 2017, which featured a male K-pop band)

Sources: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah, www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

This is part of a worrying broader trend in the modern Russian and post-Soviet interpretation of its recent political and historical past. The renewed focus on Stalin’s role in the Soviet Union’s post-war “grandeur” has meant turning a blind eye to the massive violations of human rights and freedoms committed in his name against millions of innocent people (including the politically repressed ethnic minorities).

In a world guided by economic power, political interests, and pragmatic advantages, none of the countries under study—nor even the Korean diasporas in Latin America and Eurasia—provide particularly shining examples of maintaining high standards for historical truth. Instead, they have arguably become too comfortable with their places in the “South Korea – local Korean diaspora representatives – economically and politically strategic recipient partner country in Eurasia/Latin America” triangle.

Figure 29. Scenes from unveiling the [Korean and Uzbek] People’s Friendship Monument in Uzbekistan in July 2017, the Gratitude [to the Kazakh People] Monument in Kazakhstan in September 2019, and the Greetingman in Mexico in March 2021

Sources: Koryo Saram: Zapiski o koreitsah, www.koryo-saram.ru (accessed October 4, 2021); Asociación Descendientes Coreanos de la Ciudad de México, www.facebook.com/AsociacionDescendientesCoreanosCDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Coreanos Mexicanos de Campeche, www.facebook.com/CorMexCamp/ (accessed October 4, 2021); Alianza de descendientes coreanos México-Cuba, www.facebook.com/groups/CoreaMexicoCuba1905/?ref=share (accessed October 4, 2021); La Asociación Coreana en la CDMX y Estado de México, www.facebook.com/Coreanos.en.CDMX/ (accessed October 4, 2021); “V parke Karagandi poyavilsya pamyatniy znak blagodarnosti koreyskogo naroda”, eKaraganda, ekaraganda.kz/?mod=news_read&id=89063&fbclid=IwAR0LxacqjvNYdakcNlZq9Cj23V-BK-PhO1LMbJOGO4XSAD4TPO1_mfvuPaM (accessed October 4, 2021)

While Russia and Kazakhstan have at least paid reparations to the politically repressed Koreans since the early 1990s and currently have legal schemes regarding monetary reparations to the victims of ethnic and political repressions of the Soviet past, no such measures have been adopted or even proposed by the Mexican or Uzbekistani governments, which likewise received many abused Koreans.

As for South Korea, it has been clearly overwhelmed over the last two decades by the demands of its foreign policy strategy of becoming a “middle power.” It has focused on gaining access to energy-rich markets that have trade complementarity with its own market without ever questioning their former or current authoritarian political systems. As a result, its diaspora is little more than a hefty “Trojan horse” bargaining chip that can be used when dealing with its strategic partner countries globally and locally.

The question of who should care about the human rights violations and crimes against humanity committed in the recent past against the ethnic Korean diasporas and their members in the former Soviet Union and Latin America remains open for discussion by third-party observers, who seem to be much more concerned about it than the major state players involved, as the latter are too closely intertwined in political, economic, and ethno-cultural triangles.

Figure 30. Mexico’s Port of Progreso and Merida, where the first Koreans arrived in 1905: then and now

Source: Koryo Saram: Memory in Faces. //www.facebook.com/pamyatvlitsah/ (accessed October 4, 2021)

Appendix

Table 1. South Korean economic interaction with Mexico, Russia, and Central Asia through the prism of its diasporal outreach, presidential visits, and diplomatic developments[10]

| Mexico | Russia | Kazakhstan | Uzbekistan | |

| Trading partner | No. 1 in Latin America | No. 1 in Eurasia | No. 2 in Eurasia | No. 3 in Eurasia |

| Bilateral trade volumes by 2021 | Over US$21 bn (70% growth over the last decade) | Over US$22 bn (100% growth over the last 30 years) | Almost US$10 bn (50% growth in recent years) | Over US$5 bn (50% growth in recent years) |

| Exports to SK (top products, percentage) | Crude petroleum (over 45%), zinc ore (5%), lead ore (5%), molybdenum ore (4%), vehicle parts (4%), medical instruments (3%) | Crude petroleum (45%), refined petroleum (14%), coal briquettes (14%), petroleum gas (6%), non-filet frozen fish (4%) | Crude petroleum (88%), radioactive chemicals (5%), ferroalloys (4%) | Recovered paper pulp (32%), non-retail pure cotton yarn (18%), light pure woven cotton (13%), perfume plants (7%), potassic fertilizers (4%), work trucks (4%), fruits (4%) |

| Imports from SK (top products, percentage) | Integrated circuits (20%), vehicle parts (10%), broadcasting accessories (7%), engine parts (2%), office machine parts (2%), air pumps (1.5%) | Cars (26%), vehicle parts (18%), large construction vehicles (3%), beauty products (3%), rubber tires (2%), coated flat-rolled iron (2%) | Liquid pumps (18%), steam boilers (15%), other heating machinery (13%), air pumps (6%), centrifuges (6%), valves (4%), iron structures (4%), cars (4%) | Vehicle parts (32%), cars (13%), prefabricated buildings (7%), large construction vehicles (3%), air pumps (2%), heating machinery (2%), engine parts (1.5%), liquid pumps (1.5%), iron structures (1.5%) |

| SK foreign investments by 2021 | US$7 bn with over 1,800 SK companies investing in Mexico | Over US$4 bn | Over US$7 bn | |

| Korean diaspora, number of people | 30,000 | 170,000 | 100,000 | 180,000 |

| State Visits | 2005—Roh Moo-hyun 2010, 2012— Lee Myung-bak 2016—Park Geun-hye | 2004—Roh Moo-hyn 2008—Lee Myung-bak 2017, 2018—Moon Jae-in | 2004—Roh Moo-hyun 2009—Lee Myung-bak 2014—Park Geun-hye 2019—Moon Jae-in | 2004—Roh Moo-hyun 2009, 2011— Lee Myung-bak 2014—Park Geun-hye 2019—Moon Jae-in |

| Strategic Frameworks | Strategic Partnership for Common Prosperity in the 21st Century since 2005 Friendship Society between Mexico and South Korea (its head, Mexican deputy David Bautista Rivera Morena, made May 4 a national holiday in Mexico) | Strategic Cooperative Partnership since 2008 “Korea-Russia Dialogue” since April 2010 “Russia-Korea Society” since 2014 | Comprehensive Central Asia Initiative under Roh Moo-hyun; New Asia initiative under Lee Myung-bak; Eurasia Initiative under Park Geun-hye Central Asia nicknamed “another Middle East” by ROK MoFA on its official website Annual Korea-Central Asia Cooperation Forum headed by vice foreign ministers since 2007 Korea-Central Asia Cooperation Forum Secretariat, a permanent secretariat established for the purpose of facilitating and enhancing multilateral cooperation between Korea and Central Asia (officially launched under the Korean Foundation in July 2017) | |

| Joint Initiatives | Korea-Mexico hospital and Korean migration museum in Merida opened in 2005 (Roh) Since 2012, negotiating a FTA (given a second wind in 2016 under Park) A number of economic, investment and technical agreements since 2016 (Park) 2017—Avenue of the Republic of Korea in Merida (Moon) 2019—May 4 as national Day of Korea in Mexico (corresponding legislation passed in Yucatan and Campeche) (Moon) 2021—the Greetingman (Moon) 2021—May 4 as national Day of Korean Immigrant in Mexico (passed at the federal level in Mexico DF) (Moon) | Visa-free travel agreement since January 2014 In 2018, signed documents establishing a FTA and a document establishing direct communication between air forces (Moon) 2018—Moon Jae-in becomes the first foreign leader to speak in the Russian parliament 2021—Sergey Lavrov visits SK to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the diplomatic relationship | Since 2005— Association of Kazakhstan Studies in Korea Signed a number of economic, investment, and technical agreements in 2014 (during Park’s visit) Working on the establishment of a regional FTA with Eurasian Economic Union since Nazarbayev’s visit to Seoul in 2016 Opened a Monument of Gratitude to Kazakhs from the Korean people in Karaganda in 2019 (funded by the local ethno-cultural association on its 30th anniversary) | 2010—opening of the Seoul Park, the only park in Uzbekistan managed using South Korean funds (this followed Lee’s visit in 2009) Signed a number of economic, investment, and technical agreements in 2014 (during Park’s visit) Opened a monument to the Korean and Uzbek Friendship of Peoples in 2017 in the Seoul Park (under Moon and during Seoul mayor’s visit to Uzbekistan and the Uzbek president’s visit to SK) Working on establishing a FTA since 2019 (during Moon’s visit); started discussions in January 2021 (STEP) Opening of a Palace of Korean Culture and Art by the Korean Cultural Centers Association (whose head since 2012, Victor Park, is a member of the Uzbek government) and the Overseas Koreans Foundation. (Moon) Uzbekistan has been a major recipient of Korean ODA throughout this period (as has Mexico, but in much smaller amounts) |

| Important anniversaries | 60 years of diplomatic relations in 2022 | 30 years of diplomatic relations in 2020 | 30 years of diplomatic relations in 2022 | 30 years of diplomatic relations in 2022—SK was the first country to officially recognize Uzbekistan |

[1] 1,014 upon arrival of the Mexican steamboat Hidalgo on May 15, 1905, according to the official paperwork of that time from Merida.

[2] Won-Ho Kim, “Korean-Latin American Relations: Trends and Prospects,” Asian Journal of Latin American Studies 11 (1998), http://www.ajlas.org/AJLASArticles/1998Vol11SpecialIssue/Won-Ho%20Kim%20Korean-Latin%20American%20Relations%20Trends%20and%20Prospects.pdf.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Yuna Ban, “South Korea’s Soft Power in Middle Power Diplomacy: Enhancing Popular Culture and its Challenges,” Synergy: The Journal of Contemporary Asian Studies, December 2, 2020. https://utsynergyjournal.org/2020/12/02/south-koreas-soft-power-in-middle-power-diplomacy-enhancing-popular-culture-and-its-challenges/.

[6] Sook Jong Lee, “South Korean Soft Power and How South Korea Views the Soft Power of Others,” in Public Diplomacy and Soft Power in East Asia, ed. Sook Jong Lee and Jan Melissen (Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 139-161.

[7] Lee, “South Korean Soft Power.”

[8] Ban, “South Korea’s Soft Power.”

[9] 1,014 on May 14, 1905, according to the official Mexican paperwork of that time.

[10] Based on international economic statistics, data from South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and local Korean and international press.