- This event has passed.

Politics, Religion, and Conflict Online in Central Asia

9 July, 2014 @ 4:00 PM

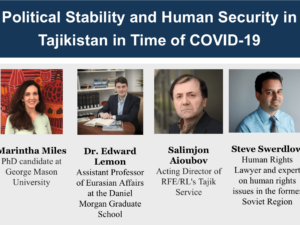

Noah Tucker (Registan.net, and CAP associate)

Sarah Kendzior (Al Jazeera and CAP associate)

Courtney Ranson (Media research consultant)

The Internet and social media are slowly beginning to revolutionize the Islamic marketplace of ideas for Central Asians. Similar to processes identified by scholars like Peter Mandaville in other contexts, Central Asia’s access to digital Islam has been delayed by low Internet penetration, authoritarian controls on media and communication, and, in part, by Central Asia’s peripheral status in the Muslim world. Advances in communications technology and large-scale migration are rapidly eroding these obstacles, however, allowing Central Asians to increasingly participate in trans-national Islamic discourses through digital media.

As Central Asians engage with the global Muslim community, debates from other social and political contexts seep into local discourse. Religious quarrels between Saudi Salafi scholars and competing styles of Islamically-inspired women’s fashion from Turkey or Egypt more often inform debates about how to be a good Muslim among young Uzbeks and Kazakhs who have no personal connection to the Middle East. While most of the content in the marketplace centers around personal piety, others topics come with new political baggage, including calls to choose sides among fratricidal jihadist factions in Syria or al Qaida influenced hate rhetoric against other Muslims groups many Central Asians have never before encountered. The process of engaging in this global marketplace remains slow and affects only a minority of the population, but it is growing at a rapid pace and remains mostly undocumented and unmonitored by both academic and government analysts.

This workshop will examine some of the many ways digital media permit people, groups and ideas previously isolated or excluded from religious and political debates in the region to circle back and re-engage networks in their countries of origin. Uzbeks forced to flee theirhomeland after the Andijon events, for example, worked together to build Uzbek language internet resources to document their experiences, to tell their own version of the Andijon tragedy that starkly contrasted official versions, and organize activists inside the country and scattered around the world seeking justice for this and countless other injustices.

Uzbeks or Tajiks living abroad for long periods as part of growing diaspora communities build on these same technologies and networks to preserve and distribute indigenous religious work banned in their home countries, like dozens of videos of sermons by Andijon imam Abduvali Qori Mirzoev, who disappeared from the Tashkent airport in 1995 and is presumed to have been killed in the custody of Uzbekistani security services. But they also acquire new language skills and specialized education that enable them to translate Islamic media produced in Arabic, Turkish or even English into their home languages, introducing popular and sometimes proscribed texts into regional languages, from works by Said Qutb and Maulana Maududi to popular reformist televangelists.

These émigrés act as bridges between information environments, often creating branded digital media studios dedicated to bringing audiovisual content they believe is religiously or politically meaningful into their home language networks where it can be quickly shared by Bluetooth between cellphones even without an internet connection. Viral videos by popular Saudi clerics like Muhammad al Arifi calling on Muslims to rage over injustice in Syria cross into Central Asian language networks quickly by multiple vectors. Interviews by out-offavor members of the Karimov family with foreign news networks or footage from Ukrainian television that challenge narratives about the violence there this year Russian state-owned television network propaganda dramatically expands the range of narratives and perspectives available to internet users beyond what they receive in heavily censored state-approved media.

Ties between global communities of Central Asians with better access to information sometimes pushes the state to allow the debates to expand, creating new space for those in the region to discuss issues that affect them. Compatriots abroad also at times introduce new material with the goal of drawing Central Asians out–to leverage a sense of global solidarity they build into mobilization for external causes, for foreign civil wars, to offer readers what they claim is a chance to create meaning for their lives by dying for a greater cause. This workshop will examine the way politics, religion, and conflict intersect online for Central Asians and discuss the way global engagement on these issues through the internet and social media might shape domestic discourse and ultimately the future of the region.

The CERIA Initiative is generously funded by the Henry Luce Foundation.