Author:

This policy brief has been developed by researchers at the Progres Foundation. The extended research on human development has been published on the organization’s website. 1 The Progres Foundation works to support various progressive educational initiatives that benefit the public in Turkmenistan. In line with this, the Progres Foundation established and continues to oversee two long-term flagship informational portals: Saglyk.org, 2 which has been working to improve public health literacy in Turkmenistan over the last 15 years, becoming a leading source of COVID-19 information in the Turkmen language; and Progres.online, 3 an online analytical journal that promotes better nuanced understanding of the societal trends in Turkmenistan by providing quality research and policy analysis.

1 Progres Foundation. Reports of Human Development in Turkmenistan. (March-May 2024). https://progres.online/category/reports/human-development/.

2 Saglyk.org is the only website that has been publishing continuous information about public health in the Turkmen language since 2009. It works with bloggers, medical experts, and artists to cover important, sometimes under-reported, health issues facing Turkmen society. https://saglyk.org.

3 Progres.online is a non-profit online journal promoting evidence-based, constructive and analytical research and writing on important socio-economic issues in Turkmenistan. It collaborates mainly with bloggers, researchers, and analysts from Turkmenistan. https://progres.online.

Introduction

Turkmenistan’s greatest yet most neglected asset is its people. Despite abundant oil and gas reserves, mismanagement has turned what could have been a foundation for sustainable growth into a vehicle for short-term profiteering. Initially viewed as a “resource blessing,” these natural assets have devolved

into a “resource curse,” with wealth failing to be invested in human capital and then translated into long-term prosperity. Research consistently shows that institutional quality and human development are the true engines of financial growth in Central Asia. 4 For the last 33 years, the government of Turkmenistan has systematically overlooked these critical areas, leading to deteriorating public health, failing educational systems, and shrinking opportunities for its citizens thus undermining the nation’s future potential.

In 2021, hydrocarbons comprised 90% of the exports of Turkmenistan, 5 and by 2023 they accounted for 74% of export revenues and 50% of the country’s GDP. 6 However, publicly available information on the state budget does not include revenues from natural resources. 7 The procedures for awarding natural resource extraction licenses and contracts are unknown. There is no publicly available data on the amount of money generated from the sales of natural resources or how these funds are being used. Similarly, the government operates the Stabilization Fund for state budget surpluses and the Foreign Exchange Reserve Fund for oil and gas revenues, but no information is available on the size of these funds or their management. 8

Meanwhile, deep disparities in access to education, healthcare, and employment persist across gender, geography, and socioeconomic background lines. Women, rural residents, and those from poor households face the brunt of these inequities. This policy brief analyzes the current state of human development in Turkmenistan and urges the international organizations and foreign embassies working in Turkmenistan to prioritize a human-centered development strategy, which is essential for achieving sustainable, long-term progress.

The research for this policy brief was carried out by using open access and publicly available resources such as the UN, the UNDP, the WHO, UNESCO, UNESCAP, OHCHR, the ILO, UNFPA, IWPR, Our World in Data, DataReportal, the BTI Project, the World Bank, USAID, OECD, the Heritage Foundation, the International Women’s Rights Action Watch, Open Democracy, the Global Data Lab, Researchgate, MICS, the Palaw Index, Saglyk.org, Progres.online, the Voluntary National Review, and national media and alternative news outlets such as Radio Free Europe and ACCA Media. We also used data from the State Statistics Committee of Turkmenistan, although it provides very limited data on human development and lacks detailed and disaggregated statistics.

4 Isiksal, A.Z. “The role of natural resources in financial expansion: evidence from Central Asia.” Financ Innov 9, 78 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-023-00482-6.

5 Jennet Hojanazarova, “Economic Trends and Prospects in Developing Asia: Caucasus and Central Asia: Turkmenistan.” Asian Development Bank, April 2023. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/863591/tkmado-april-2023.pdf.

6 UNICEF. Country Office Annual Report 2023: Turkmenistan. February 14, 2024. https://www.unicef.org/media/152091/file/Turkmenistan-2023COAR.pdf.

7 U.S. Department of State. 2023 Fiscal Transparency Report: Turkmenistan. June 27, 2023. https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-fiscal-transparency report/turkmenistan.

8 U.S. Department of State. 2024 Investment Climate Statements: Turkmenistan. Accessed on November 20, 2024. https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-investment-climate-statements/turkmenistan/.

The Human Development Index

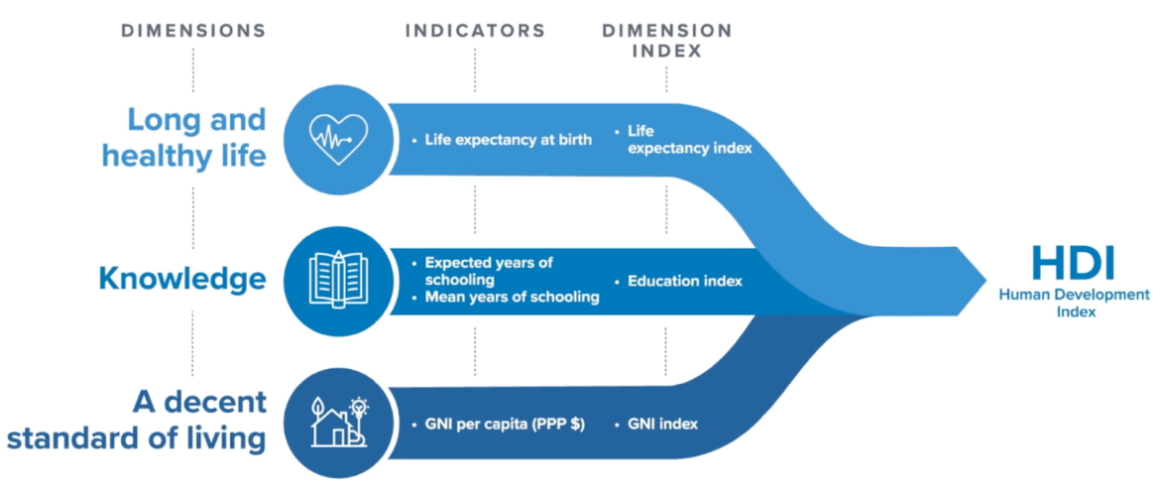

One way to assess whether Turkmenistan is properly creating the necessary opportunities for its people to grow and contribute is by measuring the country’s human development. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) defines human development as “the capability for a long and

happy life, for qualitative education and participation in the economy to lead a life with dignity.” 9 The Human Development Index (HDI) combines three essential indicators: longevity, education, and income.

Figure 1. Human Development Index Dimensions and Indicators.

Source: UNDP (2024). Human Development Reports.

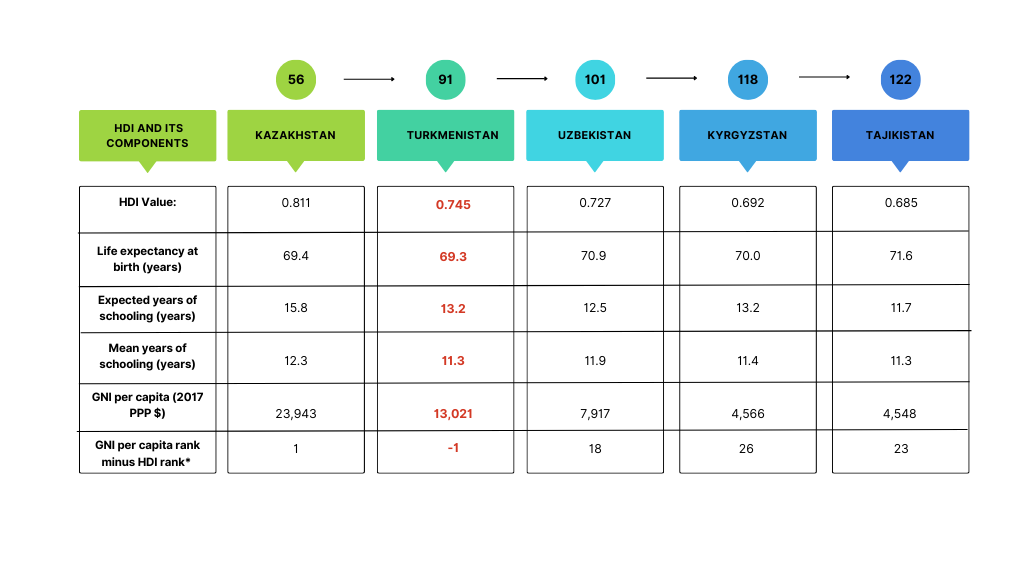

While 2022 index is available for Turkmenistan, this article uses the 2021 Human Development Index for its comprehensive data. 10 In 2021, Turkmenistan’s HDI value was 0.745, placing it in the “high human development” category. 11 While it ranks second in Central Asia after Kazakhstan on the overall HDI, closer examination shows Turkmenistan is similar to Tajikistan, the lowest performer, in its individual components. Its higher ranking is due to a high gross national income (GNI) from the oil and gas sector. Subtracting GNI per capita rank from the HDI gives Turkmenistan a negative value

(-1), the only such country in Central Asia.

Figure 2. HDI and its Components for Central Asia, 2021.

Difference in ranking by Gross National Income (GNI) per capita and by HDI value. A negative value means that the country is better ranked by GNI than by HDI value.

Source: UNDP (2021). Human Development Reports.

Between 2005 and 2021, Turkmenistan’s HDI value rose from 0.660 to 0.745, primarily due to a near doubling of GNI per capita from $7,702 to $13,021. However, other HDI components saw minimal changes. Since 2016, Turkmenistan’s dual exchange rate system has inflated GNI figures by using the

official rate (3.5 manat/USD) rather than the black-market rate (28.90 manat/USD in 2021) thus boosting its HDI ranking.

9 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). What is Human Development? February 19, 2015. https://hdr.undp.org/content/what-human-development.

10 Unlike the most recent HDI 2022 the 2021 report includes Turkmenistan in Gender Inequality Index and Gender Development Index. This also means that some of the data cited in this report became hard to locate since the UNDP has updated its relevant web pages to reflect the data for 2022. For example, under Gender Inequality Index one can no longer see data for Turkmenistan since in the most recent 2022 report the country was not included.

11 UNDP. Human Development Reports: Turkmenistan. March 13, 2024. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/specific-countrydata#/countries/TKM.

How Healthy Are the People of Turkmenistan and How Long Do They Live?

Turkmenistan has the lowest life expectancy rate in Central Asia. Between 2005 and 2021, life expectancy in Turkmenistan increased by only 3.2 years, compared to 5.1 years in Tajikistan. From 1990 to 2021, life expectancy at birth in Turkmenistan rose by just 5.3 years, while Tajikistan saw an

increase of 9.6 years. Despite Turkmenistan’s GNI per capita being 186.3% higher than Tajikistan’s, Tajik citizens live, on average, 2.3 years longer.

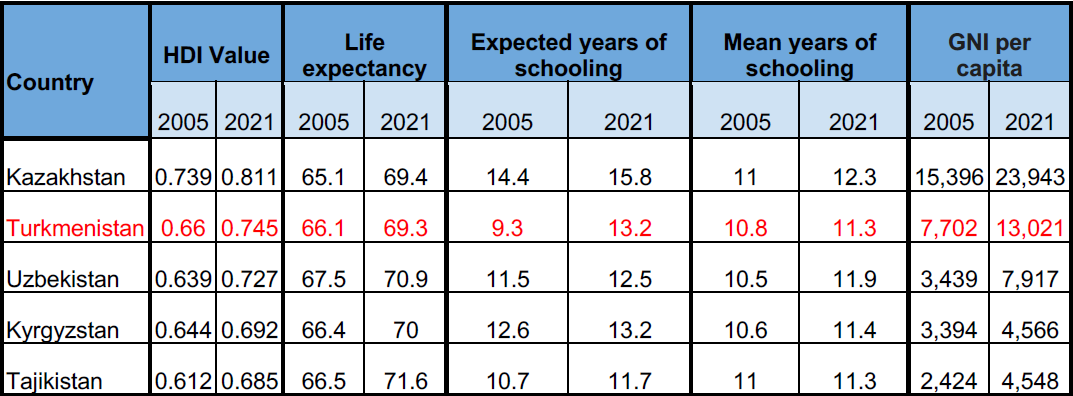

Figure 3. Comparing HDI Values and its Components for 2005 and 2021

for Central Asia.

Source: UNDP (2021). Human Development Reports.

Moreover, Turkmenistan performs poorly on “healthy life expectancy.” The World Health Organization (WHO) defines it as the average number of years that a person can expect to live in “full health” from birth. 12 In 2019 the life expectancy at birth in Turkmenistan was 69.7 years while the healthy life expectancy at birth was 62.1 years. This means Turkmens lost 7.6 years to illness and health problems.

12 World Health Organisation (WHO). Health data overview for Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 2, 2024. https://data.who.int/countries/795.

How Much Education Do People in Turkmenistan Receive?

Turkmenistan’s education levels are among the lowest in Central Asia. Expected years of schooling are 13.2 years, the second best in the region, but significantly lower than Kazakhstan’s 15.8 years. The mean years of schooling in Turkmenistan, along with Tajikistan’s, is 11.3 years, the lowest in

Central Asia. By comparison, in Kazakhstan, adults receive, on average, one more year of schooling than adults in Turkmenistan.

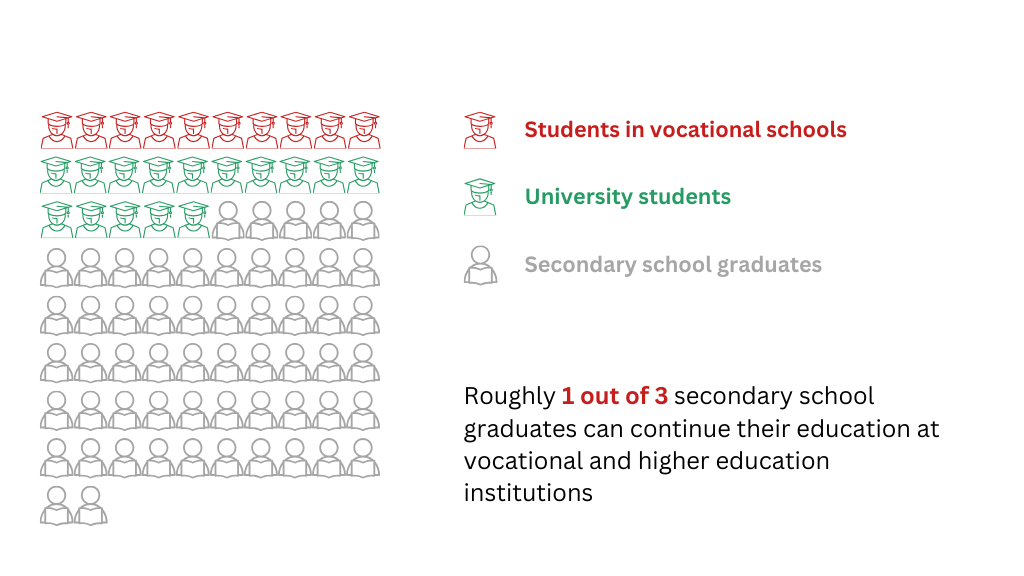

Secondary education is mandatory and free in Turkmenistan, but tertiary education is limited, with only three out of 10 secondary school graduates continuing on to a tertiary education. Despite education reforms, issues like limited university quotas and corruption hinder access to higher education, leading many students to study abroad and not return, contributing to a brain drain. 13 According to UNESCO, in 2021 there were 70,911 Turkmen nationals studying abroad. 14 As with other years of this occurrence, some of these students never return home because of widespread corruption, a lack of job opportunities, a limited and censored internet, a desire to avoid constant harassment by the authorities, or for being denied the right to leave Turkmenistan and travel abroad freely.15

Figure 4. Number of secondary school graduates and number of

students enrolled in tertiary education in Turkmenistan in 2022.

Source: Turkmenportal (2022) and Progres.online (2022).

13 Progres Foundation. How does the brain drain impact Turkmen society? January 8, 2021. https://progres.online/economy/how-does-the-brain-drain-impact-turkmen-society/.

14 UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). Data by theme. Accesses December 4, 2024. http://data.uis.unesco.org/index.aspx?queryid=3806#. Note: To find the exact datapoint readers should search the ‘data by theme’ on the left side bar on the UIS webpage. Using the filters as follows: Education: Number and rates of international mobile students: Outbound internationally mobile students by host region: Total outbound internationally mobile tertiary students studying abroad, both sexes.

15 Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR). Foreign Study Provides Escape for Turkmen Students. January 13, 2012. https://iwpr.net/global-voices/foreign-study-provides-escape-turkmen-students

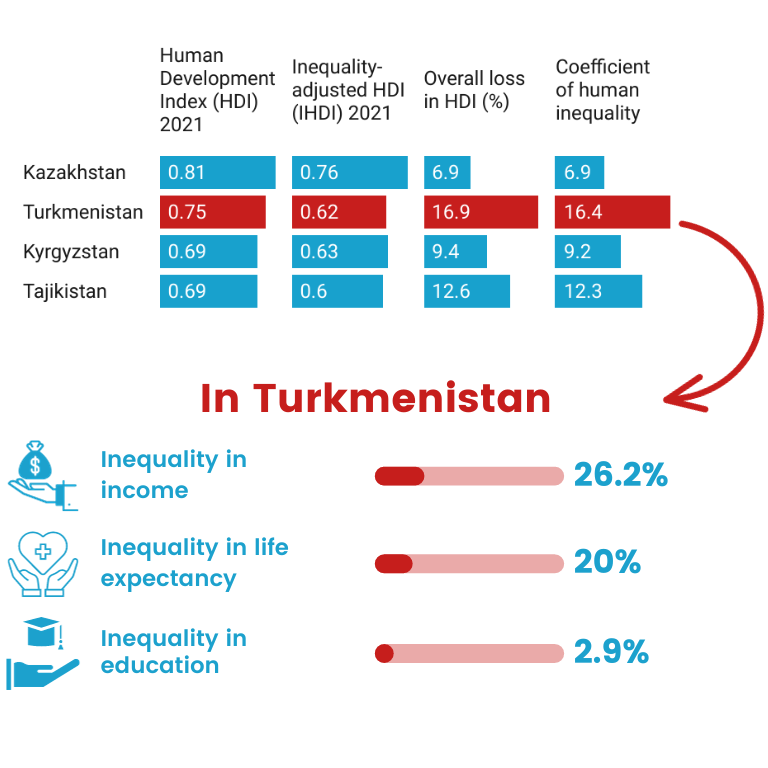

Unveiling Inequality in Human Development

Given that the HDI is an average measure of basic human development, what it conceals in its measurement is the inequality of the distribution of human development across the population. This is why it is useful to look at the inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI), which takes into account inequalities

in health, education, and income. 16 The gap between these inequalities, as seen in a comparison of the HDI and IHDI, reflects the “loss in human development”: Turkmenistan loses 16.9% of its human development potential due to the inequalities, which is the biggest loss among Central Asian countries.

Figure 5. Inequality Adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) for

Central Asia, 2021.

Uzbekistan is missing from the chart due to lack of data.

Source: UNDP (2021) Inequality Adjusted Human Development Index.

Income inequality is the biggest disparity in Turkmenistan, with the richest 1% holding 19.9% of the nation’s income – the highest disparity rate in Central Asia. 17 This figure might be even higher if the unofficial wealth accumulation from government bribes was taken into account. Such inequality limits opportunities for better living standards, stable finances, and access to quality healthcare and education, all of which greatly affect future generations.

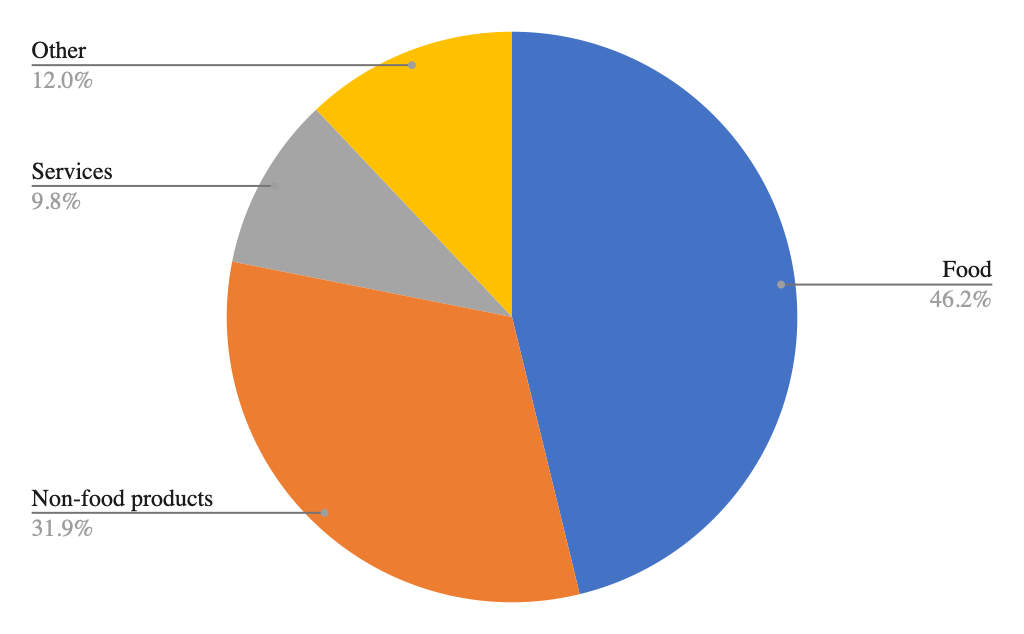

Despite annual 10% salary increases for public sector employees, inflation outpaces those raises. For example, the Palaw Index shows that while the minimum wage rose from 870 TMT in 2020 to 957 TMT in 2021, the affordable portions of palaw for a family dropped from 13.2 to 10. 18 As illustrated

in Figure 6, the largest share of total household expenses goes to food, the cost of which increased from 46.2% in 2018 to 52.9% in 2022. Given that this is a fairly high share, significant increases in food prices are likely to increase the burden on household budgets. Food expenses in Turkmenistan are significantly higher compared to other upper-middle-income countries like Turkey (27.3%) and Russia (29%). 19

Figure 6. The structure of household expenditures in 2018

Source: UN (2019) Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan (VNR).

Inequality extends to healthcare, with a 20% disparity in life expectancy, the highest in the region. In education, inequality is lower (2.9%) due to free, compulsory secondary education. However, higher education faces challenges, as at least four out of five university spots are filled through bribes (up to

several tens of thousands of dollars per place) in addition to tuition fees. 20 Consequently, Turkmenistan has one of the lowest higher education rates globally, with just over 80 students per 10,000 citizens in the 2020–2021 academic year. 21 In comparison, even in 1989 there were 117 students per 10,000.

16 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Inequality Adjusted Human Development Index. Accessed on November 20, 2024. https://hdr.undp.org/inequality-adjusted-human-development-index#/indicies/IHDI.

17 UNDP. Inequality Adjusted Human Development Index. Accessed on November 20, 2024. https://hdr.undp.org/inequality-adjusted-human development-index#/indicies/IHDI. Note: The data for IHDI for Turkmenistan is for 2021 because the latest index for 2022 does not include Turkmenistan. However, because of the updates the website no longer contains the data for 2021. Readers can scroll down and go to ‘Documentation and Downloads’ page to explore and download data for previous years. There, you can filter by Index (IHDI), year (2021), and country (Turkmenistan). However, it provides indicator level data and not the detailed data for income gaps between different income groups.

18 Progres Foundation. Palaw Index special report: How much palaw can you afford this Gurban Bayramy compared to previous years? July 10, 2023. https://progres.online/palaw-index/palaw-index-special-report-how-much-palaw-can-you-afford-thisgurban-bayramy-compared-to-previous-years/. 19 Our World in Data. Share of expenditure spent on food vs. total consumer expenditure, 2022. Accessed on December 4, 2024. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/food-expenditure-share-gdp?country=AZE~BLR~RUS~TUR~KAZ.

20 Bertelsmann Stiftung. BTI 2022 Country Report – Turkmenistan. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2022. Accessed on December 4, 2024. https://btiproject.org/fileadmin/api/content/en/downloads/reports/country_report_2022_TKM.pdf.

21 Bertelsmann Stiftung. BTI 2024 Country Report – Turkmenistan. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2024. Accessed on December 4, 2024, https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/TKM.

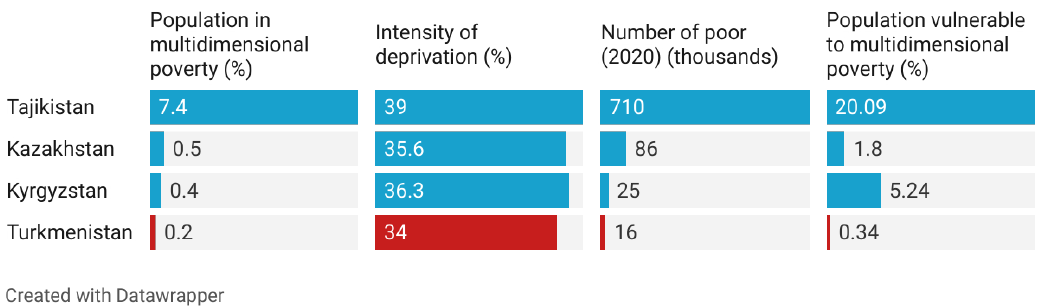

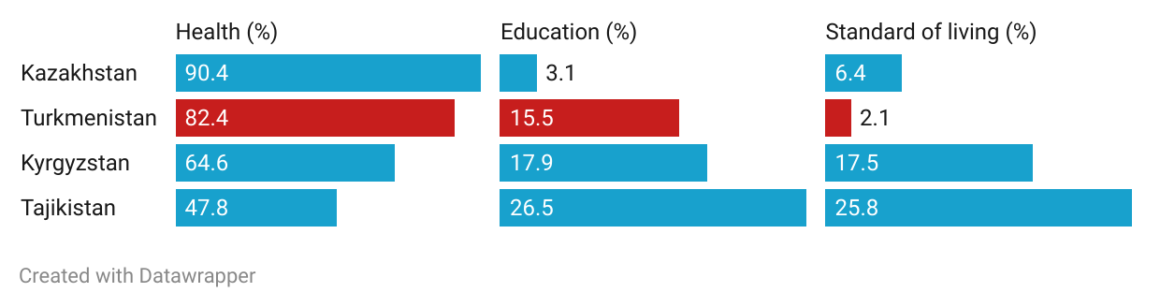

The Impact of Poverty on Education and Economic Opportunities

Turkmenistan lacks an official national poverty line and reliable statistics on poverty. According to the 2021 Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), which assesses deprivations in health, education, and living standards, 0.2% of the population (16,000 people) are multidimensionally poor, and 0.3% (21,000 people) are vulnerable to it. 22 Despite having the smallest proportion of people at risk of multidimensional poverty in Central Asia, the actual number of people living in poverty may be significantly higher. For instance, a 2018 UNESCAP country brief estimated that nearly 22% of Turkmenistan’s population lived in poverty, with an additional 5% in extreme poverty, surviving on less than $1.90 a day. 23

Figure 7. Multidimensional Poverty in Central Asia, 2021.

Source: UNDP (2021) Multidimensional Poverty Index.

Poverty limits access to higher education in Turkmenistan, with only 3% of poorer individuals completing tertiary education compared to 15% of wealthier individuals. 24 Household income and place of residence significantly impact educational opportunities, trapping those from poor families in a cycle of poverty. 25 Addressing poverty requires not only providing survival means but also improving access to opportunities for education and employment.

Figure 8. Percentage of the Multidimensional Poverty Index attributed to deprivations in each dimension.

Source: UNDP (2021) Multidimensional Poverty Index.

22 UNDP. Briefing note for countries on the 2023 Multidimensional Poverty Index: Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 4, 2024. https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/Country-Profiles/MPI/TKM.pdf.

23 UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). Inequality of Opportunity in Asia and the Pacific: Country Brief: Turkmenistan. November 2018. https://repository.unescap.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12870/4336/ESCAP-2018-PB-Inequality-opportunity Turkmenistan.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

24 UNESCAP. Leaving No One Behind (LNOB) Country Briefs: Turkmenistan LNOB Brief-MICS (2019). October 25, 2022. https://lnob.unescap.org/node/378127. 25 UNESCAP. Inequality of Opportunity in Asia and the Pacific: Country Brief: Turkmenistan. November 2018. https://repository.unescap.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12870/4336/ESCAP-2018-PB-Inequality-opportunity-Turkmenistan.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Deficiencies in Healthcare, Education, and Living Standards

Turkmenistan’s human development is hindered by deficiencies in healthcare, education, and living standards, as highlighted by the Quality of Human Development dashboard. Figure 9 summarizes some of the indicators available for Turkmenistan. 26 In Turkmenistan, the lost health expectancy, or difference between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy, is 11.2%, indicating significant health issues. The country has only 22.2 physicians and 40 hospital beds per 10,000 people, compared to 39.8 physicians and 61 beds in Kazakhstan. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of adequate medical infrastructure for timely care.

Figure 9. Quality of human development in Turkmenistan.

Source: UNDP (2021) Human Development Reports.

Educational quality is also lacking. There is one trained teacher for every 26 students, compared to 17 in Kazakhstan. Only 34% of primary and secondary schools have internet access 27, while Uzbekistan’s figures are 98% and 88%, respectively. Turkmenistan’s internet penetration is 41.4% 28, significantly

lower than Kazakhstan’s 86%. 29 The benefits of the internet in education are enormous, as it can promote learning and development of both students and teachers. 30

Additionally, literacy and numeracy skills are underdeveloped in Turkmenistan. Boys score 20.6% and girls 19.9% in these areas. Only 53.2% of children in grades 2–3 can complete basic literacy and numeracy tasks. 31 Moreover, 59% of children in Turkmenistan lack access to organized pre-primary

education, significantly hindering their early development and future academic progress. 32 Living standards in Turkmenistan are low and unequal among the population. Over 26% of employed people are in vulnerable employment, lacking decent earnings, working conditions, and social security,

compared to 20.7% in Kazakhstan. Although official unemployment rates are reported at 4 – 5%, actual unemployment may be around 60%, with only 25% of the workforce being regularly employed in 2020.33 Most self-employed individuals work in low-income sectors like agriculture or retail and have minimal social security. Securing well-paid jobs often requires connections or bribes. 34 According to UNESCAP, unequal access to opportunities in Turkmenistan is influenced by household wealth, residence, and education. In 2018, access to bank accounts and full-time employment showed disparities of at least 50 percentage points between the most and least advantaged groups. 35

Figure 10. Drivers of inequality in access to different opportunities.

Source: UNESCAP (2018) Country Brief for Turkmenistan 2018.

26 UNDP. Quality of Human Development Dashboard. https://hdr.undp.org/quality-human-development. Note: The first draft of this article was written in 2023 using Human Development Reports, the HDI and thematic composite indices. However, since the UNDP published data for 2022 and since then the old dataset for 2021 is no longer available on their website. 27 United Nations (UN). Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan: On the progress of implementation of the Global Agenda for Sustainable Development 2023. Page 177. Accessed on November 23, 2024. https://turkmenistan.un.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/VNR-2023%20Turkmenistan%20Report%20EN.pdf.

28 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan. Page 189.

29 Kemp, Simon. “Digital Kazakhstan.” Datareportal. February 23, 2024. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-kazakhstan. Note: Internet penetration in Kazakhstan was 85.9% at the start of 2022 and 92% at the start of 2024.

30 Progres Foundation. The benefits of Internet in education: Why is it urgent to make it work without VPN in Turkmenistan? July

5, 2022. https://progres.online/internet-literacy/the-benefits-of-internet-in-education-why-is-it-urgent-to-make-itwork-without-vpn-in-turkmenistan/.

31 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan. Page 78-79.

32 Ibid.

33 Bertelsmann Stiftung. BTI 2024 Country Report – Turkmenistan. 34 Ibid.

35 UNESCAP. Inequality of Opportunity in Asia and the Pacific: Country Brief: Turkmenistan.

Geographic Inequalities in Access to Resources and Opportunities

In Turkmenistan gaps remain between the best-off and the worst-off groups in access to different opportunities, which is illustrated in Figure 11. Bolded indicators on the top have the largest difference between these two groups.

Figure 11. The gaps between the furthest behind and the furthest ahead

groups in Turkmenistan across all available indicators, 2019.

*Note: standard analysis with 6,195 observations. The orange circle represents the average rate of the furthest behind group, the blue circle represents the average rate of the furthest ahead group, and the gray bar represents the difference between these two groups.

**From the chart VAW stands for violence against women, HH – household, IND – individual.

Source: UNESCAP (2019) Leaving No One Behind.

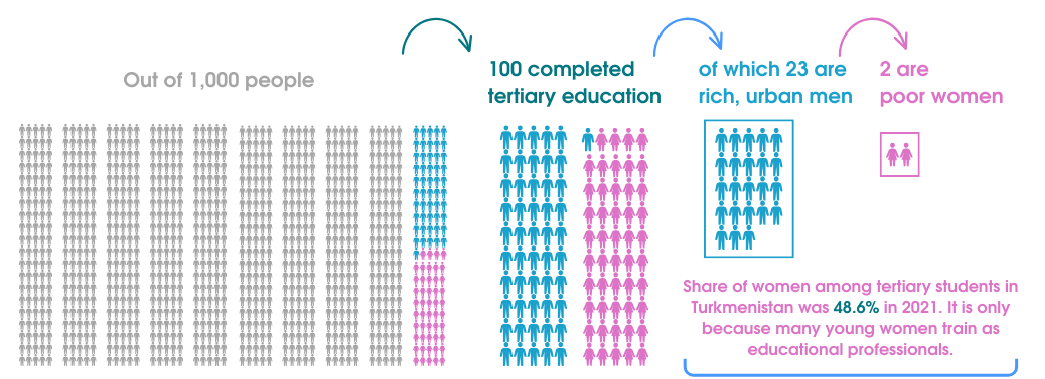

The Dissimilarity Index highlights the greatest inequality in access to tertiary education among 25–35- year-olds in Turkmenistan (D-Index of 0.33). 36 Only 10% of Turkmenistan’s population holds a tertiary degree. Education access is highly influenced by a person’s income, gender, and location. To

illustrate, just 2% of poorer women complete tertiary education versus 23% of wealthier men in urban areas. Addressing these educational disparities could reduce inequality and improve economic opportunities.

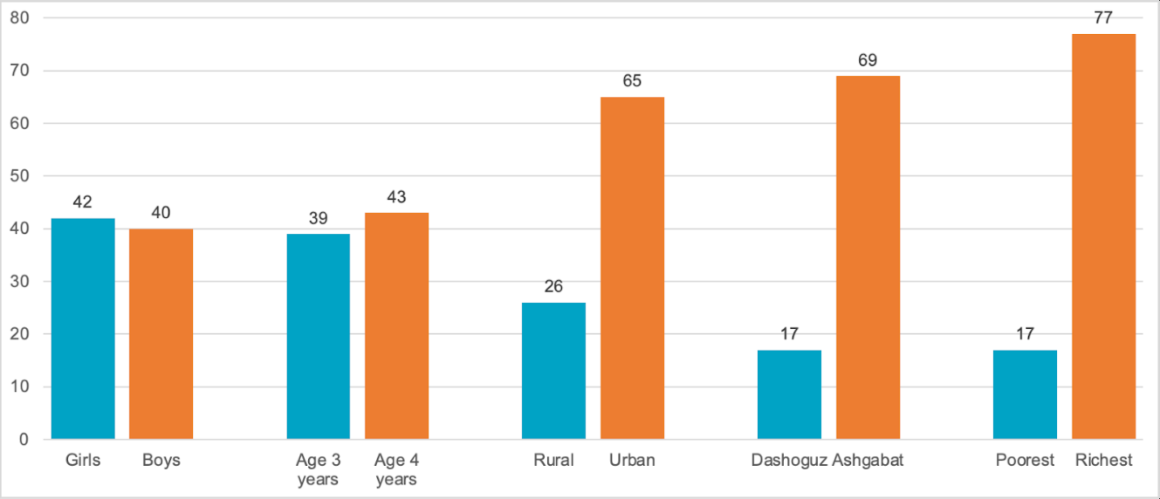

Similarly, access to resources and opportunities in Turkmenistan varies greatly based on geographic location. The most significant disparity is in early childhood education, where only 19% of rural children with three or more siblings have completed early education, compared to 75% in urban areas with fewer siblings. The gap between Ashgabat and other regions is notable, with 69% of children in Ashgabat attending pre-primary education compared to just 17% in Dashoguz province. 37

Figure 12. Attendance at early childhood education programs, 2019

Source: Turkmenistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2019.

Moreover, rural residents, who make up 52.9% of the population, 38 face large-scale poverty and unequal opportunities. Salaries in rural areas are 33% lower than in cities, and poverty rates are higher. Rural youths have limited educational opportunities due to a paucity of secondary schools in the

provinces, while access to full-time jobs is constrained by educational attainment, perpetuating poverty cycles. 39

Communication technology access also varies, with urban residents having three times more internet access than rural residents. In 2022, only 23.3% of rural schools had internet access compared to 64.4% in urban areas. Infrastructure for students with disabilities is also limited in rural areas. 40

Figure 13. The gap in access to organized learning and the Internet at schools in urban vs rural areas.

Source: MICS (2019) and VNR (2023).

There is also health disparities based on a person’s residence. For instance, Ashgabat residents live an average of 4.5 years longer than those in Mary. Historical decisions, such as the closure of regional hospitals and the firing of 15,000 medical workers, have led to inadequate healthcare facilities in rural

areas. 41 Despite some reforms, rural healthcare remains under-resourced and poorly managed. 42 Children in rural areas face high risks for poor health. Stunting rates are higher in rural areas (7.9%) compared to urban areas (5.8%). In Mary province one in every 10 children faces an increased risk of

stunting. 43 This impacts children’s future productivity and highlights the need for targeted interventions.

The Soviet-era “propiska” system further exacerbates disparities by restricting internal migration. 44 Rural residents struggle to move to cities for better opportunities due to registration barriers, which are also a source of corruption. This policy limits access to housing, employment, education, and

healthcare, reinforcing inequalities and stifling social mobility.

36 UNESCAP. The Dissimilarity Index. Leaving No One Behind (LNOB). Accesses on November 21, 2024. https://lnob.unescap.org/lnob?indicator=1043&geo=350&year=2019. 37 UNICEF. Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) Turkmenistan 2019. Accessed on November 21, 2024. https://mics.unicef.org/surveys?display=card&f[0]=region:4276.

38 State Committee of Turkmenistan on Statistics (TurkmenStat). Итоги сплошной переписи населения и жилищного фонда Туркменистана 2022 года [Results of the complete census of population and housing stock of Turkmenistan in 2022]. Accessed on November 21, 2024. https://www.stat.gov.tm.

39 Bertelsmann Stiftung. BTI 2024 Country Report – Turkmenistan.

40 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan. Page 177. 41 Farangis Najibullah. “Real State Of Turkmen Medical Care A Far Cry From Official Images.” RFE/RL’s Turkmen Service. April 6, 2014. https://www.rferl.org/a/turkmenistan-health-care-shortcomings/25322982.html.

42 Sebastien Peyrouse. “The Health of the Nation – the Wealth of the Homeland! Turkmenistan’s Potemkin Healthcare System.” PONARS EURASIA. February 13, 2019. https://www.ponarseurasia.org/the-health-of-the-nation-the-wealthof-the-homeland-turkmenistan-s-potemkin-healthcare-system/.

43 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan. Page 54-55.

44 Progres Foundation. Propiska düzgünini reformirlemelimi? [Should the propiska rule be reformed?]. August 17, 2021. https://progres.online/tk/jemgyyet/propiska-duzgunini-reformirlemelimi/.

Gender Disparities in Human Development

To incorporate a gender-sensitive perspective into the Human Development Index, the UNDP introduced the Gender Development Index (GDI) 45 in 1995 and the Gender Inequality Index (GII) 46 in 2010. These measures evaluate gender disparities in key aspects of development. In Turkmenistan,

gender differences in human development are evident: women have a lower HDI score (0.726) compared to men (0.760), with the largest gaps in the Akhal and Mary regions. The GII, which assesses reproductive health, empowerment, and labor market outcomes, places Turkmenistan at 0.177,

ranking it 43rd out of 170 countries.

Figure 14. Tertiary education completion rates by gender.

Source: UNESCAP (2022) Leaving No One Behind.

Education Disparities

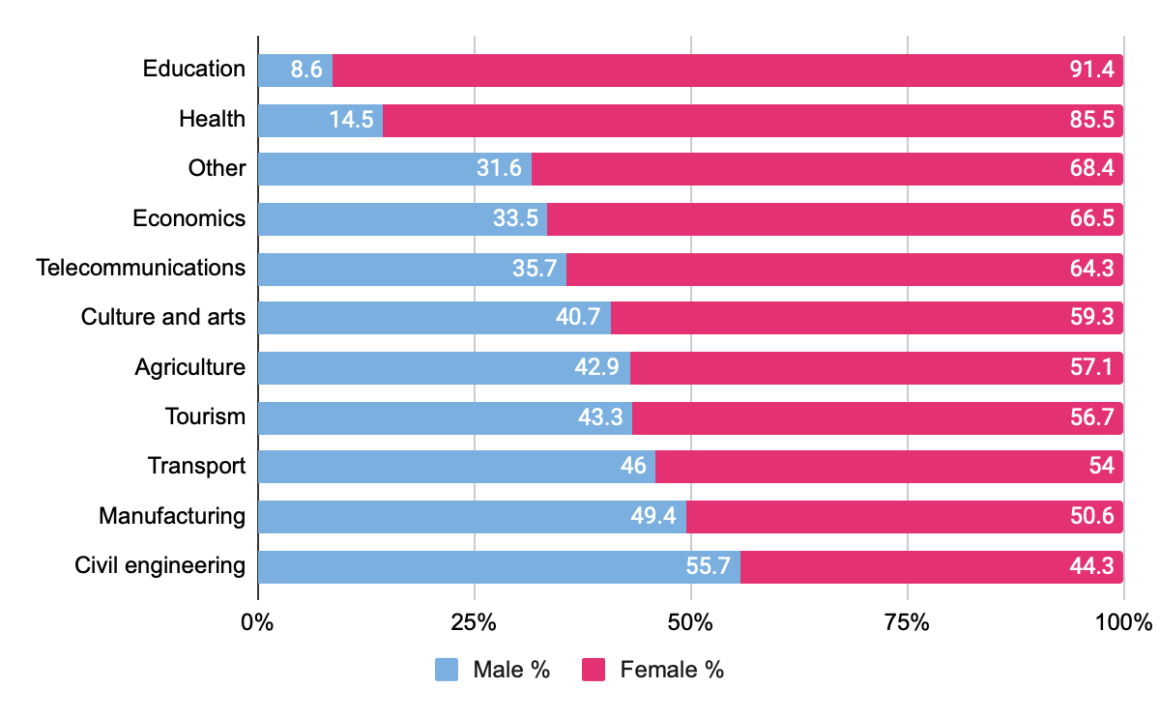

Women in Turkmenistan have less access to higher education than men. The average years of schooling for women is 10.9, compared to 11.6 for men. 47 While it is true that women do attend vocational schools in numbers greater than men (women comprise 64.3% of the student enrollment in 2022), the disparity in women’s access to higher education is made clear by their underrepresentation in universities (women comprise only 42.3% there). 48 Though women’s enrollment in tertiary education in Turkmenistan has increased from 11.8% in 2019 to 18.2% in 2022, it remains considerably lower than in upper-middle-income countries (68.8% for women). 49 Women in Turkmenistan mostly specialize in low-paying fields such as education and healthcare, with 82.3% of primary school teachers being women. 50

Figure 15. Gender distribution of students at mid-level professional

education institutions by specialty, 2020–2021 academic year.

Source: SDG 4: Quality Education. 51

45 UNDP. Gender Development Index (GDI). Human Development Reports. https://hdr.undp.org/gender-developmentindex#/indicies/GDI. Note: The initial article was written in 2023 using GDI data for 2021. Since then UNDP has published 2022 data which does not include Turkmenistan. However, since the website was updated the data for 2021 is no longer available on UNDP website.

46 UNDP. Gender Inequality Index (GII). Human Development Reports. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematiccomposite-indices/gender-inequality-index#/indicies/GII. Note: The initial article was written in 2023 using GII data for 2021. Since then UNDP has published 2022 data which does not include Turkmenistan. However, since the website was updated the data for 2021 is no longer available on UNDP website.

47 Note: Since the UNDP wesbite was updated with 2022 report, the data for 2021 is no longer available on their website. https://hdr.undp.org/gender-development-index#/indicies/GDI. 48 UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). Data by theme. Accessed December 4, 2024. http://data.uis.unesco.org/#. Note: To find the relevant data readers should use the ‘data by theme’ on the left side bar on the webpage and search for Enrolment by level of education: Enrolment in tertiary education ISCED-5 programs, which is equivalent to short-cycle tertiary education, and ISCED-6 which is equivalent of bachelor’s degree. It is possible to see data by gender.

49 World Bank. Gender Data Portal: School enrollment, tertiary (% gross). Accessed December 4, 2024. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/indicator/se-ter-enrr?geos=TKM_KGZ_UMC_ECS&view=trend.

50 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023. Page 87.

51 The original source of the data was published as a pdf presentation on the Asia-Pacific Learning and Education 2030+Networking Group hosted on the UNESCO website, under the SDG4 Knowledge Hub. Unfortunately, the direct page containing the document is no longer available because it has either been archived or is no longer accessible directly through their website. https://apa.sdg4education2030.org/sites/apa.sdg4education2030.org/files/2021-05/ENG_Republic of Turkmenistan-min.pdf.

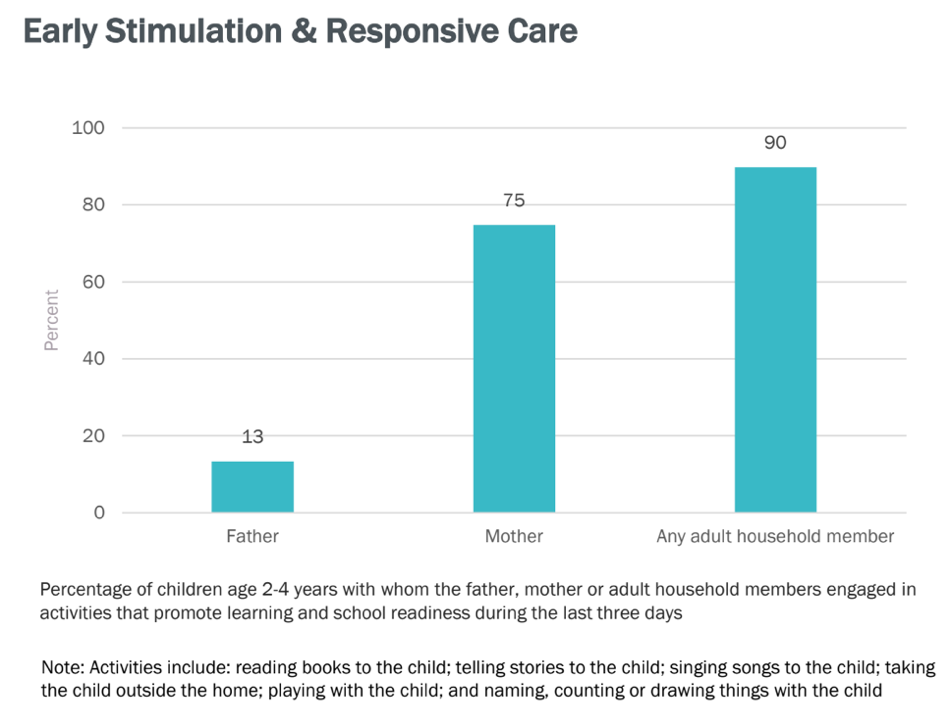

Labor Market Disparities

Women in Turkmenistan face significant challenges in the labor market, including high rates of unemployment and underemployment. Factors such as lower education levels, unpaid domestic work, early marriage, and societal expectations contribute to this issue. In 2019, women made up 91.4% of domestic workers, 52 and the number of housewives was nine times higher than that of men who remained in the home as the caretaker of the home. 53 Women perform 2.5 times more household chores than men and are almost six times more likely to engage in child-related learning activities. 54 The labor force participation rate for women was 36.5% in 2021, compared to 55.6% for men, making Turkmenistan second only to Tajikistan in gender disparity in this area. 55 Women are more likely to be in vulnerable employment (30.1%) than men (27.9%), lacking formal work arrangements and social

protections. 56

Figure 16. Percentage of children age 2–4 years with whom the father,

mother, or adult household members engages in activities that promote

learning and school readiness.

*Note: Activities include: reading books, telling stories, singing songs to the child; taking the child outside the home; playing, naming, counting or drawing things with the child.

Source: Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) 2019.

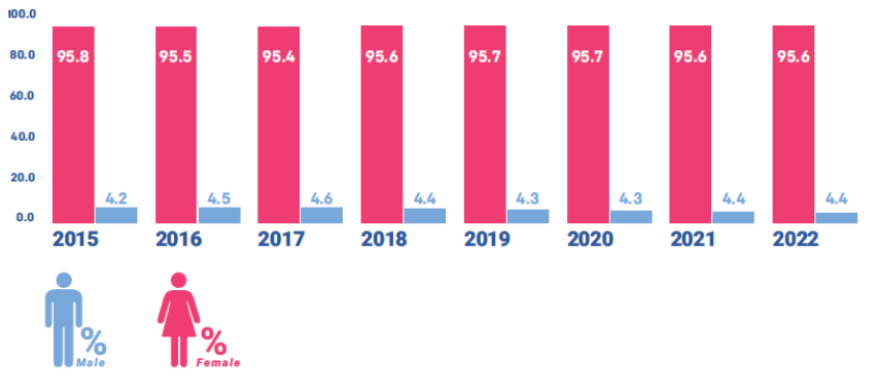

Sector-wise, more women work in services (51.1%) compared to men (34.7%), while men dominate industry (44.1% vs. 25.7% for women). 57 Women constitute 73.9% of healthcare workers and the majority of teachers, with 95.6% in pre-primary, 82.8% in primary, and 61.8% in secondary education. 58

Figure 17. Ratio of male to female teachers in pre-primary schools.

Source: Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023.

In the private sector, women made up 42.5% of employees in large and medium-sized enterprises but held only 22.4% of managerial positions in 2022. 59 The share of women entrepreneurs dropped from 32.5% in 2022 60 to 22.4% in 2023. 61 Women also face unequal access to land, receiving only 901 out of 4,616 land parcels allocated by the Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs in 2022. 62

52 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2019. Page 34.

53 Niyazova, Bilbil. “Türkmenistanyň oglanlary we gyzlary şeýle tapawutlymy? [Are boys and girls in Turkmenistan that different?].” July 24, 2021. https://public.flourish.studio/story/711888/.

54 Ibid.

55 UNDP. Gender Inequality Index (GII). Human Development Reports. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematiccomposite-indices/gender-inequality-index#/indicies/GII. Note: The initial article was written in 2023 using GII data for 2021. Since then UNDP has published 2022 data which does not include Turkmenistan. However, since the wesbite was updated the data for 2021 is no longer available on UNDP website.

56 World Bank School enrollment, tertiary (% gross). Gender Data Portal. Accessed December 4, 2024 https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/economies/turkmenistan. 57 USAID. Turkmenistan: Sector Detail: Gender. Accessed on December 6, 2024/https://idea.usaid.gov/cd/turkmenistan/gender.

58 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023. Page 87

59 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023. Page 92, 97.

60 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023. Page 98.

61 UN. 2037th Meeting, 87th Session, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW): Consideration of Turkmenistan. February 2, 2024. https://webtv.un.org/en/asset/k1g/k1gh3o5gro.

62 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023. Page 98.

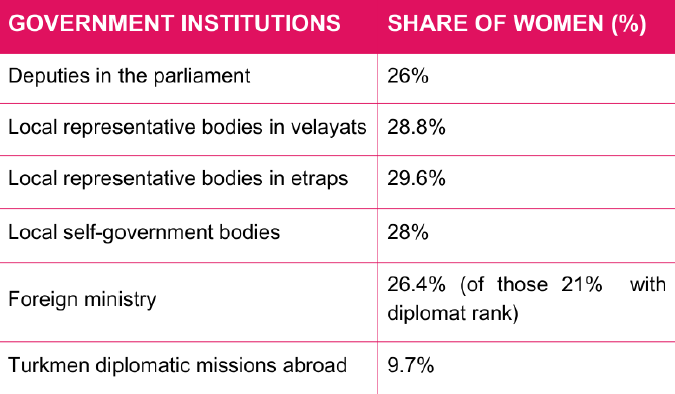

Decision-Making Representation

Women hold fewer decision-making positions with men occupying three times more seats in the national parliament and almost five times as many seats in the People’s Council (Halk Maslahaty) as women (2022). 63

Figure 18. The share of women in various government institutions.

Source: Turkmen Delegation’s Presentation at CEDAW (2024).

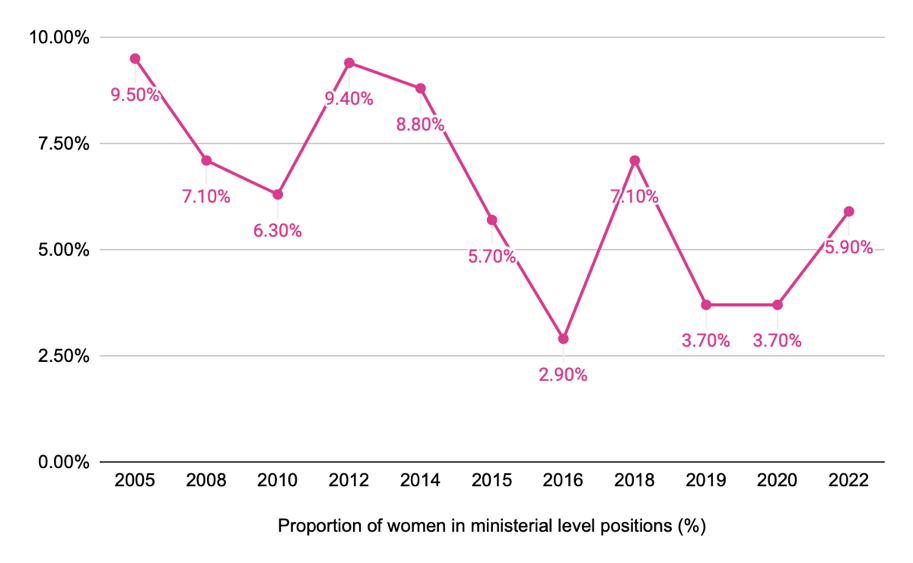

Women’s representation in local governments and leadership roles has stagnated or declined. In local governments, the proportion of seats held by women decreased from 22.1% in 2018 to 21.7% in 2022. 64 At the ministerial level women’s representation fell from 9.5% in 2005 to 5.9% in 2022. 65 By comparison, Tajikistan has 14.3% of women in ministerial positions. Similarly, in Turkmenistan, women in managerial positions dropped from 24.1% in 2016 to 22.4% in 2022. 66

Figure 19. Proportion of women in ministerial level positions (%).

Source: World Bank Gender Data Portal (2022).

In academia, the proportion of women as academic staff at tertiary institutions decreased from 50.1% in 2014 67 to 47% in 2023. 68

63 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023. Page 97. 64 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023. Page 180.

65 World Bank. Proportion of women in ministerial level positions (%). Gender Data Portal. Accessed on December 6, 2024.

https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/indicator/sg-gen-mnst-zs?geos=WLD_TKM_KAZ_KGZ_UZB&view=trend.

66 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023. Page 180. 67 World Bank. Tertiary education, academic staff (% female) for Turkmenistan for 2014. Gender Data Portal. Accessed on

December 6, 2024. https://liveprod.worldbank.org/en/indicator/se-ter-tchr-fe-zs?year=2014.

68 UN. 2037th Meeting, 87th Session, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW): Consideration of Turkmenistan. February 2, 2024. https://webtv.un.org/en/asset/k1g/k1gh3o5gro.

Income Disparities

Despite women’s income nearly doubling from 2005 to 2021, men still earned 1.83 times more than women. In 2021, women earned an average of USD 9,227, while men earned USD 16,884. 69 This income gap is consistent across regions, with Ashgabat having the largest disparity.70

Figure 20. Gross national income per capita in Turkmenistan by gender.

Source: Gender Development Index for Turkmenistan (2021).

Women’s wages were 12.2% lower than men’s in 2022, 71 with gaps of 32% in extractive industries and 22.5% in retail and wholesale sales positions. 72 Although the constitution guarantees equal pay for equal work, women earned less in almost all sectors, from 69.6% of men’s salaries in public administration and defense, to 95.1% in education. The International Labour Organization (ILO) notes that the gender pay gap is due to educational attainment, career length, job segregation, and stereotypes about women’s aspirations and capabilities. 73 This leads to the undervaluation of traditionally female jobs compared to male-dominated sectors. Income disparities also affect women’s decision-making, as only 24% of household financial decisions are made by women. 74 So even though it is more likely that a woman would be remaining in the home on a daily basis, rather than a man, thus allowing her to be more aware of what is needed to run the home, women make less than a quarter of the financial decisions for their home.

69 UNDP. Human Development Reports: Turkmenistan. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/specific-countrydata#/countries/TKM. Note: Since UNDP updated its website using the most recent data for 2022, the data for 2021 is no longer available. And since Turkmenistan was not included for GDI for 2022 one cannot access the data for 2021 when Turkmenistan was included in the Index.

70 Note: Global Data Lab used to have subnational gender data for Turkmenistan, which is no longer accessible on their website. Previously one could search by using filters: Gender Development, Subnational GDI, Subnational Regions by years. https://globaldatalab.org/shdi/table/sgdi/TKM/?levels=1+4&interpolation=0&extrapolation=0. 71 Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Third periodic report submitted by Turkmenistan under articles 16 and 17 of the Covenant, due in 2023. Page 16. Accessed October 13, 2023.

https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=E%2FC.12%2FTKM%2F3&Lang=en.

72 International Labour Organisation (ILO). Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100) – Turkmenistan (Ratification:1997). Accessed on December 6, 2024. https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:13101:0::NO::P13101_COMMENT_ID:4122496.

73 ILO. Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100) – Turkmenistan (Ratification: 1997). Accessed on December 6, 2024. https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:13101:0::NO::P13101_COMMENT_ID:4122496.

74 Niyazova, “Türkmenistanyň oglanlary we gyzlary şeýle tapawutlymy? [Are boys and girls in Turkmenistan that different?].”

Health and Autonomy

Women in Turkmenistan live 6.8 years longer than men but face more health challenges. Women represent 12.7% of vulnerable persons covered by social assistance compared to 1.8% of men in 2021. 75 Half of Turkmen women lack access to contraception 76 and nearly 60% cannot make

autonomous decisions on healthcare, contraception, and consent to sex. 77 Contraception use has declined since 2000 (61.8% vs 49.7% in 2019) with one in ten married women lacking adequate family planning. This issue is particularly acute among young (89%), rural (54%), and impoverished women (53%). 78 A recent restrictive abortion law exacerbates the problem. 79 Investing in contraceptive access can yield substantial benefits. A UNFPA study shows that increased contraceptive coverage could prevent 680,000 unintended pregnancies and 22,500 unsafe abortions, saving over $87.5 million. Every $1 invested in family planning yields over $7 in public health system savings while also empowering women and strengthening public health. 80

75 ILO STAT Data Explorer: Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 6, 2024. https://rshiny.ilo.org/dataexplorer22/?lang=en&segment=indicator&id=SDG_0131_SEX_SOC_RT_A&ref_area=AZE. Note: To access the exact data readers should search on ILOSTAT Data Explorer using filters for region: Central Asia; country: Turkmenistan; and filter by gender.

76 Saglyk.org. Türkmenistanda Aýallaryň 50% Nähili Ýagdaýda [What is the situation of 50% of women in Turkmenistan?]. June 15, https://saglyk.org/makalalar/sagdyn-durmus/zenan-saglygy/1763-turkmenistanda-ayallaryn-50-nahiliyagdayda.html.

77 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Expanding choices for women and girls will save $87mln for Turkmenistan, UNFPA study finds. July 9, 2021. https://turkmenistan.unfpa.org/en/news/expanding-choices-women-and-girls-willsave-87mln-turkmenistan-unfpa-study-finds.

78 The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Turkmenistan MICS 2019 Datasets, Survey Findings and Snapshots. July 10, 2020. https://mics.unicef.org/news/just-released-turkmenistan-2019-datasets-survey-findings-and-snapshots.

79 Aynabat Yaylymova. “Turkmenistan cut our abortion rights overnight. Our ‘allies’ did nothing.” May 4, 2022. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/turkmenistan-abortion-rights-five-weeks-un-eu/.

80 UNFPA. Expanding choices for women and girls will save $87mln for Turkmenistan, UNFPA study finds.

Violence and Social Norms

Early marriage and childbearing, prevalent in Turkmenistan, hinder women’s economic independence. With 27 births per 1,000 girls aged 15–19 in 2023, 81 limited bodily autonomy fueled sexual and genderbased violence, 82 virginity tests, 83 as well as restrictions such as not obtaining a driver’s license. 84 A national report revealed alarming rates of domestic violence, with 58% of women believing that their husbands have the right to beat them. 85 Spousal control, including restricting women’s work and education, is widespread. 86 Progres Foundation’s social media analysis shows a disturbing rise in online violence against women (2021 – 2.8% vs 2022 – 18%), with hate speech and harmful gender roles dominating the conversation. 87 Turkmenistan lacks laws and programs to prevent domestic violence and sexual harassment.

81 UNFPA. World Population Dashboard: Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 6, 2024. https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/TM. Note: Adolescent birth rate per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 has decreased to 22 in 2024.

82 UN Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan releases first-ever national survey on health and status of a woman in the family. August 26, 2022. https://turkmenistan.un.org/en/196699-turkmenistan-releases-first-ever-national-survey-health-and-status-womanfamily.

83 Radio Azatlyk. В Дашогузе мобильные телефоны школьников проверяют на наличие порнографии, а у девочек и наличие девственности [In Dashoguz, mobile phones of schoolboys checked for pornography, and girls checked for virginity]. February 6, 2018. https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29021912.html.

84 ACCA Media. In Turkmenistan, authorities deprive women of driver license. November 27, 2019. https://acca.media/en/2538/in-turkmenistan-authorities-deprive-women-of-driver-license/.

85 UNFPA. Health and Status of a Woman in the Family in Turkmenistan. August 9, 2022. Page 16. https://turkmenistan.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pubpdf/ report_health_and_status_of_a_woman_in_the_family_in_turkmenistan.pdf.

86 UNFPA. Health and Status of a Woman in the Family in Turkmenistan.

87 Progres Foundation. Digital Violence as a Mirror to Offline Realities: What does the public in Turkmenistan think about the

status of women and girls? March 8, 2023. https://progres.online/reports/gender-equality/digital-violence-as-a-mirrorto-offline-realities/.

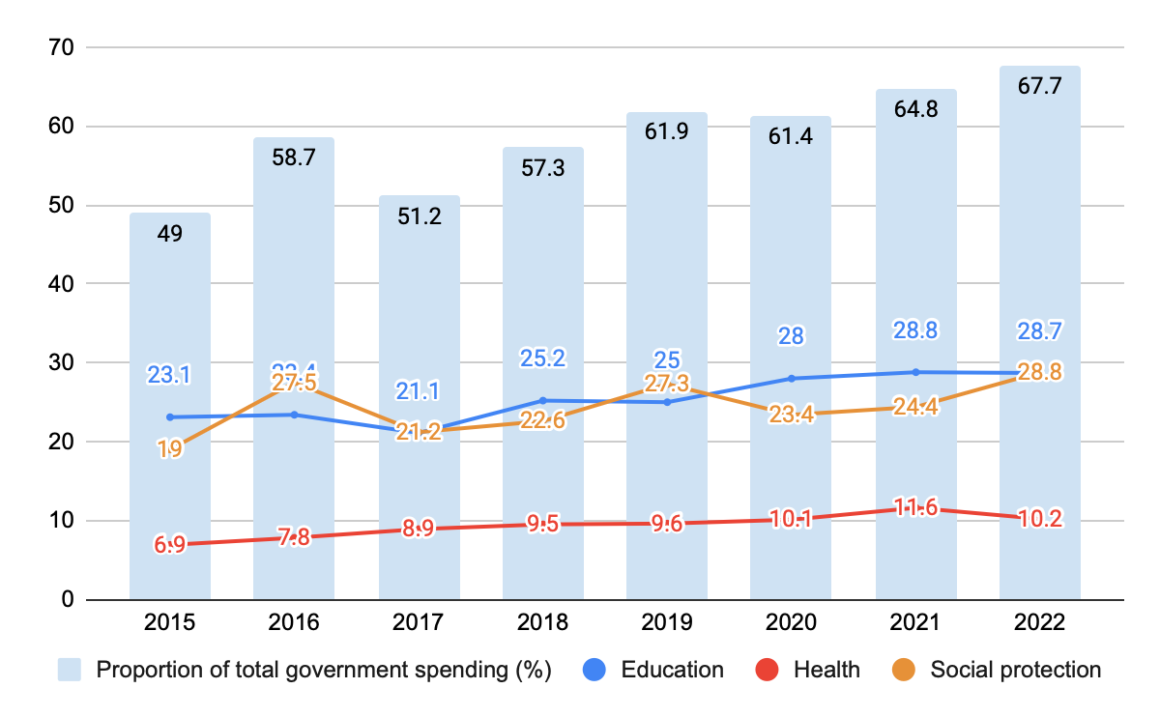

Turkmenistan’s Underinvestment in Health and Education

Turkmenistan allocates significant budget shares to health and education, yet outcomes lag. While the social sector consumed 61.4% 88 of the 2020 budget, 89 education dwarfed healthcare spending. However, data transparency is limited, hindering accurate analysis.

Figure 21. Share of social expenditures within the total amount of public

expenditures in Turkmenistan, by percentage.

Source: Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan (2023).

88 UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan 2023. Page 166.

89 Turkmenportal. State budget performance for 2020 approved in Turkmenistan. November 1, 2021. https://turkmenportal.com/en/blog/40981/state-budget-performance-for-2020-approved-in-turkmenistan.

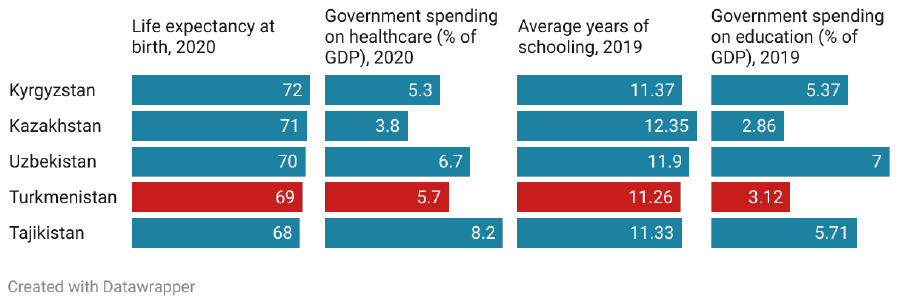

International Comparisons

Data inconsistencies complicate analyses of Turkmenistan’s public spending on health and education. The WHO reported healthcare spending at 5.7% of the GDP in 2020, 90 and UNESCO documented education spending at 3.12% in 2019. 91 Meanwhile, using the World Bank GDP data 92 and the Heritage Foundation’s government spending estimate 93 suggest that education spending aligns with international reports at approximately 3.16% of the GDP, but healthcare spending is significantly lower at 1.14%, contradicting the WHO’s data.

Figure 22. Comparing Central Asian countries’ performance in health

and education with government spending in these areas.

Source: World Bank, WHO, Global Data Lab, and UNESCO.

90 World Health Organisation (WHO). Health Expenditure Profile: Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_profile/Index/en. Note: to reach the data readers should click the tab Visualisations and filter for Health Expenditure Profile for Turkmenistan.

91 UNESCO. Government expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP for Turkmenistan. Institute for Statistics (UIS). Accessed on December 8, 2024. http://data.uis.unesco.org/index.aspx?queryid=3865#. Note: To reach the data readers should search on the website right hand side search bar by using the following filters: Education: Other policy relevant indicators: Government expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP: Turkmenistan.

92 World Bank. GDP (current US$) – Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=TM.

93 Heritage Foundation. Economic Freedom Country Profile: Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://www.heritage.org/index/pages/country-pages/turkmenistan.

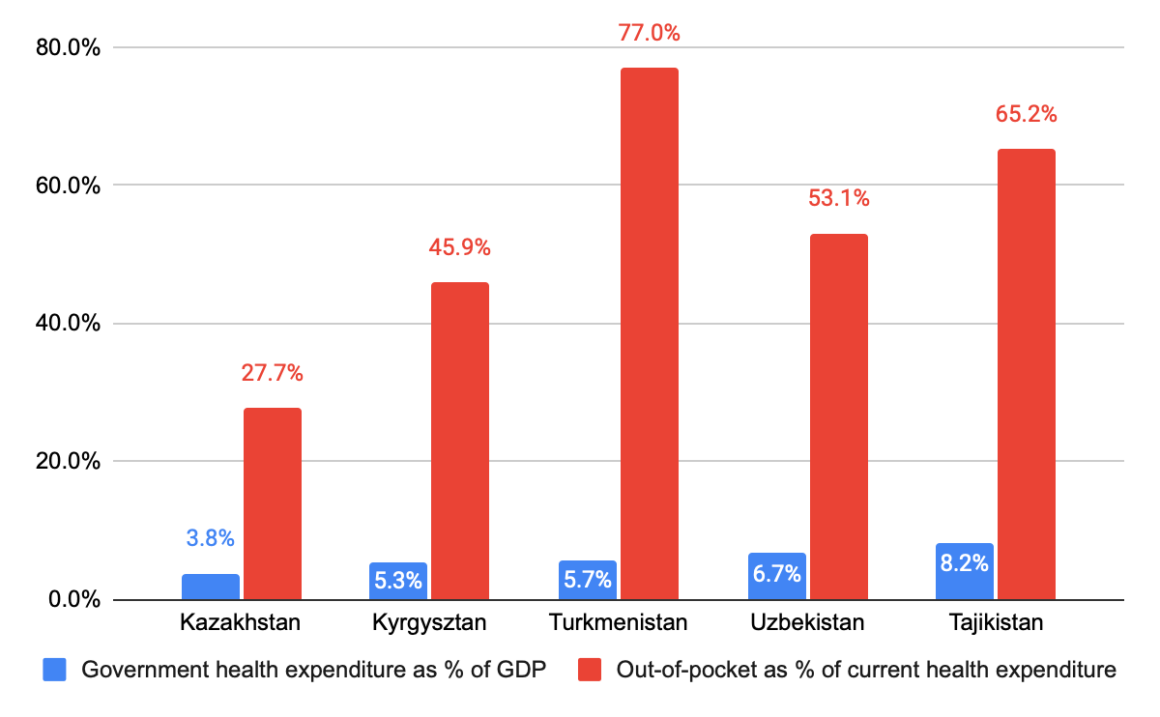

Out-of-Pocket Expenditures

Turkmen citizens bear most healthcare costs. In 2020, health expenditure per capita was $483.740, with households covering 77% out of pocket (OOP). 94 In comparison, it was 27.7% in Kazakhstan. High OOP costs can discourage citizens from seeking medical care, leading to worsening health outcomes and financial hardship. Turkmen households spend 52.9% of their total expenditures on food and 32% on non-food products, including pharmaceuticals, leaving little for other needs.

Figure 23. Comparing domestic general government health expenditure

as a percentage of the GDP and out-of-pocket spending as a percentage

of the current health expenditure in 2020.

Source: World Health Organization (2020).

94 WHO Health Expenditure Profile: Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_profile/Index/en. Note: to reach the data readers should click the tab Visualisations and filter for Health Expenditure Profile for Turkmenistan and look for Out of pocket spending as % of health spending.

Education Expenses

Many young people in Turkmenistan finance their higher education abroad due to limited local university quotas and corruption. In 2021, 70,911 Turkmen nationals studied abroad, mainly in Russia and Turkey. 95 Most students are self-financed, with average annual tuition costs of $1,572 in Russia 96 and $495 in Turkey, 97 excluding living expenses. The minimum wage in Turkmenistan in 2021 was USD 33.11, 98 and the average salary in 2023 was USD 128.00 99 using the market exchange rates, making higher education unaffordable for many families. Bertelsmann Stiftung (BTI) describes the education sector in Turkmenistan as extremely critical due to low levels of spending and investment in education, acute shortages of qualified teachers and science-based teaching materials, education curricula being overloaded with ideologized “social science,” and insufficient spending in research and development.100

95 UNESCO. Data by theme. Institute for Statistics (UIS). Accesses December 4, 2024. http://data.uis.unesco.org/index.aspx?queryid=3806#. Note: To find the exact datapoint readers should search the ‘data by theme’ on the left side bar on UIS. They should use the filters as follows: Education: Number and rates of international mobile students: Outbound internationally mobile students by host region: Total outbound internationally mobile tertiary students studying abroad, both sexes.

96 Statista. Average consumer price of studying at public higher education institutions per semester in Russia from 2016 to 2023. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1237897/averagetuitionfeeatpublicuniversitiesrussia/#:~:text=One%20semester%20of%20studies%20at,26%20thousand%20Russian%20rubles%20lower.

97 FindCourse.com. Cost of Studying in Turkey. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://www.findcourse.com/en/highereducation/article/cost-of studying-in-turkey. 98 Turkmenportal. Starting from January 1, 2021, Turkmenistan will increase salaries, pensions, state benefits and scholarships. October 9, 2020. https://turkmenportal.com/en/blog/31110/starting-from-january-1-2021-turkmenistan-will-increasesalaries-pensions-state-benefits-and-scholarships.

99 Progres Foundation. Wages in Turkmenistan will increase again by 10%. Does it beat inflation? December 12, 2023. https://progres.online/economy/wages-in-turkmenistan-will-increase-again-by-10-does-it-beat-inflation/.

100 Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2024 Country Report – Turkmenistan.

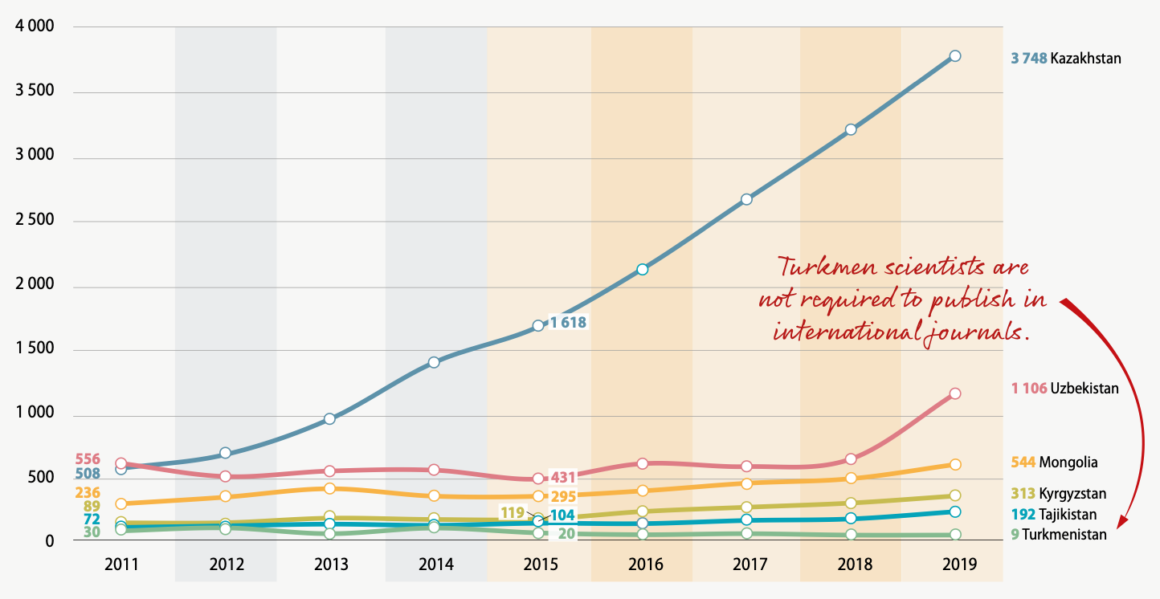

Research and Development (R&D)

Government spending on R&D is minimal, at 0.13% of the GDP in 2021,101 compared to the 1.56% average in upper-middle-income countries. 102 This low investment results in limited scientific research output, with only two scientific publications per million inhabitants in 2019, compared to 202 in Kazakhstan. 103 Only 159 PhD students were enrolled in Turkmenistan in 2015, compared to 3,603 in Kazakhstan. As research confirms, government spending on R&D is a key driver for economic performance along with the available component of human capital and a country’s trade openness.104

Figure 24. Trends in scientific publishing and patenting in Central Asia as

represented by the volumes of scientific publications, 2011–2019.

Source: UNESCO Science Report (2021).

In addition to the amount of spending, the effectiveness of spending is also crucial. Despite increased spending on the social sector, Turkmenistan has not seen commensurate improvements in development indicators. While Kazakhstan spends less on healthcare and education than Turkmenistan, people there enjoy an additional two years of life expectancy and an extra year of schooling on average. These disparities highlight potential inefficiencies in resource allocation.

101 UNESCO. UNESCO Science Report 2021: Central Asia. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://www.unesco.org/reports/science/2021/en/centralasia? TSPD_101_R0=080713870fab2000a5bc0cf7baa5f5b881ba4396fcd8784f0994414bd45fe50530421dc7cc12cc0608859d0030143000254e7e01af9951b7a280a5d99927bba0d4b2b8e153acfa55ac4d96ddb31698fb8e4e935abf9127fef6ace29154cb2071.

102 UNESCO. Science, technology and innovation: Research and development expenditure as a proportion of GDP. Accessed on December 4, 2024. http://data.uis.unesco.org/index.aspx?queryid=3684.

103 UNESCO, UNESCO Science Report 2021: Central Asia.

104 Irena Szarowská. “Importance of R&D expenditure for economic growth in selected CEE countries. E+M Ekonomie a Management.” December 2018. 21. 108-124. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329724399_Importance_of_RD_expenditure_for_economic_growth_in_selected_CEE_countries.

Recommendations to international organizations and foreign embassies

International organizations (IOs) have some political clout over the Turkmen government, in part because the government in Turkmenistan is invested in maintaining its perceived international image. In using their policy-changing and policy-making influence, IOs must be careful not to become complicit in masking the serious problems that exist in Turkmenistan nor aid in perpetuating these problems by giving a veneer of legitimacy to the government’s policies. Many of their policies are not only ineffective but often dangerously misleading as was the case during the Covid-19 pandemic when the government outright denied the existence of the pandemic while at the same time perpetuated misinformation about how to avoid contracting and spreading the disease.

Moreover, IOs are often perceived as having failed to address the needs of the population in Turkmenistan or as being too closely aligned with the government. This is due to the lack of public communication and public relations, resulting in the fact that very few outside of Ashgabat city are

aware of the work and impact of the IOs in Turkmenistan. While many of the country’s people see how the state media uses IOs to legitimize the government and its policies, very few have access to the internet and social media to share that information. This lack of transparency with the population coupled with the lack of active support of the population can damage IOs’ reputations and undermine their current credibility among the general public. To build greater visibility and trust with the people of Turkmenistan, IOs should increase their public outreach and citizen engagement, especially in remote and rural areas and actively publish and promote their activities in the Turkmen language.

The promotion of human development in Turkmenistan by international organizations such as the various UN agencies, the EU, the US Embassy, USAID, OSCE, EBRD, ADB, the World Bank, IMF, and others is both a moral responsibility and a strategic priority that is essential for reducing poverty, enhancing human rights, and promoting global stability. By improving education and healthcare, and guiding the country’s public institutions in the direction of a civil society, IOs can create long-term political and economic stability that will foster growth and new investment opportunities while building goodwill with the population.

Below are a number of policy recommendations that offer many ways that international organizations and foreign embassies can significantly improve the lives of the Turkmen people by promoting sustainable development in all sectors of Turkmenistan.

Short-term policy recommendations to IOs working with existing

institutions

- Encourage and prioritize data collection and dissemination: Through bilateral and multilateral engagement with the government of Turkmenistan, IOs should push for the collection of accurate and disaggregated data as well as make this data publicly available. Lack of data negatively impacts any IO’s ability to decide on the necessary intervention programs, evaluate effectiveness of these programs, report on their progress to the public and donors, or make meaningful international comparisons. IOs must critically evaluate any data that the government provides, then exercise caution before using and resharing it in order to actively promote transparency and openness.

- Promote and implement projects in the public health sector: The true state of public health in Turkmenistan is hard to assess given the opaqueness of the healthcare system. The 2010 report from Doctors Without Borders,105 which even almost 15 years later still accurately represents the local reality, demonstrates how serious healthcare issues in Turkmenistan are being driven underground due to a systematic denial and manipulation of data. As USAID highlights, “Turkmenistan’s growing tuberculosis (TB) epidemic presents a challenge not only to its public health system but also to the country’s long-term economic resilience.”106 This is why it is essential for IOs to encourage greater data collection and dissemination about disease spread and severity, provide training and knowledge-sharing opportunities for medical staff in Turkmenistan, promote international best practices in healthcare provisions, engage medical personnel from rural areas in national level projects, and provide financial and technical assistance to better equip rural medical facilities. The Covid-19 pandemic has illustrated the impossibility of restraining an epidemic within a country’s borders and the ensuing negative consequences it can have on human life and health, their livelihoods, and their overall wellbeing. Some efforts must be made by IOs to mitigate these outcomes as much as possible.

- Promote access to quality education and learning: The education system in Turkmenistan is highly centralized and lacks modern learning methodologies that encourage innovation, experimentation, and out-of-box thinking. Quality education is a crucial factor both for human development and for a country’s long-term progress. IOs should work closely with the Ministry of Education, universities, and vocational and secondary schools to improve their quality of education through teacher training, access to the internet, access to international learning resources and methodologies, and through exchange programs for teachers and students. Additionally, IOs can expand access to higher education by providing scholarships, grants, and study abroad opportunities so that Turkmen youth can pursue higher education, academic research, and practical experience abroad. Likewise, establishing partnerships between international and Turkmen universities could facilitate greater knowledge and student and staff exchange, and help improve the quality and variety of learning opportunities in the country.

- Support entrepreneurship and labor mobility: Citizens of Turkmenistan do not have access to high quality and meaningful jobs nor to the many other possible ways of fulfilling their potential. One-way IOs could help is by developing the practical business skills and economic and entrepreneurship education for youth and adults through secondary and vocational schools, universities, and out-of-school learning programs. Given the lack of employment opportunities, promoting and financially supporting entrepreneurship can encourage youth and adults in Turkmenistan to start their own businesses, leading not only to the achievement of self-sufficiency but also to creating new jobs and promoting economic growth in the country. IOs could also encourage the government to eliminate “propiska” and promote greater mobility of citizens inside and outside the country. People can find ways to support themselves and their families if they are not restricted from searching for and benefiting from such opportunities, be it in major cities like Ashgabat or abroad.

- Promote gender equality: There is an alarming increase in conservatism and the strict upholding of traditional gender roles in Turkmenistan, both of which inhibit girls’ and women’s ability to secure and experience their fundamental rights and freedoms. Working together with the government, public associations, and the private sector, IOs can support girls’ and women’s rights by promoting greater gender equality through improved access to education, reproductive health services, employment, leadership roles, and financial resources. In the area of the gender wage gap, IOs need to encourage the government to implement the ILO’s recommendations for gender equality that address the current underlying causes of this gap – gender-based discrimination, gender stereotypes relating to aspirations, preferences, and the abilities of women as well as vertical and horizontal occupational segregation – and the vital need to promote women’s access to a wider range of job opportunities at all levels.

- Support and collaborate with Turkmen civil society, both inside and outside the country: While there is a lack of independent civil society and media organizations in Turkmenistan, there are few government-sponsored non-governmental organizations (GONGOs) and a few independent civil society organizations abroad.107 Given the restrictive environment in Turkmenistan, many civic activists and civil society groups had to emigrate and/or establish themselves overseas. IOs should engage, collaborate, and support the work of both of these types of organizations to increase their own impact and effectiveness in Turkmenistan. Involving these organizations in regional, national, and international projects and providing them with capacity building information and funding can help them continue their work and have a positive impact on Turkmenistan.

- Engage and work with the Turkmen diaspora: While it is unclear exactly how many Turkmens study, live, or work abroad, it is clear that the number is at least in the thousands. As the research shows, migrants from Eurasian countries, regardless of the destination country, are more highly educated than the average migrant. For instance, in 2010, the average emigration rate for people with post-secondary education worldwide was 5.4% while for Turkmenistan it was 10% to 20%. 108 A large share of this group is highly educated and experienced professionals who could provide the needed human capital and financial resources to foster Turkmenistan’s development. IOs should engage and work with this group by hiring them as experts, consultants, and mentors for their projects in Turkmenistan to facilitate knowledge transfer, build connections between Turkmens at home and abroad, and foster collaboration between Turkmenistan and the host countries.

105 Doctors Without Borders. Turkmenistan’s Opaque Health System. April 12, 2010. https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/latest/turkmenistans-opaque-health-system.

106 USAID. Our Work: Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://www.usaid.gov/turkmenistan/our-work. 107 Progres Foundation. Civil Society Inside and Outside Turkmenistan: Searching for Meaningful Engagement in the Interest of the Turkmen Public. April 22, 2024. https://progres.online/reports/civil-society/civil-society-inside-and-outsideturkmenistan-searching-for-meaningful-engagement-in-the-interest-of-the-turkmen-public/.

108 Tim Heleniak. “Diasporas and Development in Post-Communist Eurasia. Migration Policy Institute (MPI).” June 28, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/diasporas-and-development-post-communist-eurasia.

Long-term policy recommendations to IOs that involve reforming existing institutions and current methods of engagement

- Promote democracy and good governance: Turkmenistan is notorious for its unreformed public sector and the endemic corruption in the public sector, its lack of support for democratic institutions, its lack of respect for human rights, its intolerance of media freedom and the non-existence of an independent civil society, its non-promotion of citizenry access to the internet, and its prevention of public participation in decision-making. There is a wide gap between the constitution and the written laws, and their application in practice. To the greatest extent possible, IOs should tie their engagement in Turkmenistan to meaningful and measurable political and governance reforms.

- Promote independent civil society and media: Human development is tightly linked to a person’s ability to access information and exercise their rights and fundamental freedoms. An exclusively state-controlled media and limited internet availability in Turkmenistan make it impossible for citizens to access alternative sources of information. It is of paramount importance that every project or involvement by IOs in Turkmenistan promotes the creation and existence of an independent civil society and media and moreover, to support and welcome their members as equal partners. IOs should use their privileged role and political clout to encourage the government to allow the registration of independent civil society and media organizations as the necessary step for including them in policymaking, to provide them with financial support, and to allow them to raise funds from local and international donors and to participate in international projects where they can collaborate with their peers from abroad. IOs should also support the civil society organizations abroad and help foster their connection and collaboration with GONGOs based in Turkmenistan.

- Facilitate economic reforms: Turkmenistan lacks a free-market economy and suffers from an ineffective centrally planned economy. IOs such as UNDP, USAID, EBRD, ADB, the World Bank, and IMF are in a position to help Turkmenistan implement economic reforms in a vast number of areas that will accomplish some or all of the following: reduce pervasive state intervention and state ownership, minimize reliance on the extractive sector, diversify its economy, improve investment opportunities, attract foreign direct investment, foster private sector development, promote greater competition, merge the dual exchange rates, allow foreign currency conversion, diversify trade partners, create meaningful jobs, increase government transparency, and promote regional and global trade. It would also be beneficial to encourage and promote more equitable and inclusive regional development through greater investments in rural areas in order to build crucial infrastructure such as roads, schools, better equipped hospitals, access to the internet, and the creation of local jobs.

- Promote greater collaboration with diverse group of government officials: A lack of attention paid to positive human development necessarily limits the potential for successful cooperation among IOs, the Turkmen government, and the general public. Turkmen government delegates participating in international forums or reporting on Turkmenistan’s international obligations showcase the lack of competence, professionalism, awareness of global trends, and the ability to articulate and accept the existing challenges in Turkmenistan. To positively alter these very non-productive and potentially harmful representations of Turkmenistan to the rest of the world, IOs must engage and collaborate with government officials at the various ministries and levels of government to encourage greater agency and initiative-taking as well as to educate these officials on the importance of accepting and addressing policy challenges. Helping establish partnerships, professional exchanges, and experience-sharing with policymakers in Central Asia, Caucasus, Europe, and the US could also serve as a great learning opportunity for Turkmen officials.

- Support environmental sustainability: Turkmenistan faces serious environmental challenges associated with rising temperatures, declining water resources, and a changing climate, all of which endanger people’s livelihoods and food security and contribute to environmental migration. Through their engagement with projects in Turkmenistan, IOs should help develop and support educational and in-the-field improvements that will create better water management techniques and an effective response to the changing climate, encourage the reduction of methane emissions, and minimize the country’s dependence on fossil fuels by promoting and building the infrastructure for clean and renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. Additionally, there is an urgent need for comprehensive research and data collection to evaluate these challenges and inform effective solutions.

Bibliography

ACCA Media. In Turkmenistan, authorities deprive women of driver license. November 27, 2019. https://acca.media/en/2538/in-turkmenistan-authorities-deprive-women-of-driver-license/.

Bertelsmann Stiftung. BTI 2022 Country Report: Turkmenistan. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2022.Accessed November 20, 2024. https://btiproject. org/fileadmin/api/content/en/downloads/reports/country_report_2022_TKM.pdf.

Bertelsmann Stiftung. BTI 2024 Country Report: Turkmenistan. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2024. Accessed November 20, 2024. https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/TKM.

Doctors Without Borders. Turkmenistan’s Opaque Health System. April 12, 2010. https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/latest/turkmenistans-opaque-health-system.

FindCourse.com. Cost of Studying in Turkey. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://www.findcourse.com/en/highereducation/article/cost-of-studying-in-turkey.

Heleniak, Tim. “Diasporas and Development in Post-Communist Eurasia. Migration Policy Institute (MPI).” June 28, 2013. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/diasporas-and-development-postcommunist-eurasia.

Heritage Foundation. Economic Freedom Country Profile: Turkmenistan. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://www.heritage.org/index/pages/country pages/turkmenistan.

Hojanazarova, Jennet. “Economic Trends and Prospects in Developing Asia: Caucasus and Central Asia: Turkmenistan.”Asian Development Bank, April 2023. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/863591/tkm-ado-april-2023.pdf. Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR). Foreign Study Provides Escape for Turkmen Students. January 13, 2012. https://iwpr.net/global-voices/foreign-study-provides-escape-turkmen-students.

International Labour Organisation (ILO). Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100) – Turkmenistan (Ratification: 1997). Accessed on December 6, 2024. https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:13101:0::NO::P13101_COMMENT_ID:4122496. ILO. Turkmenistan. ILOSTAT Data Explorer. Accessed on December 6, 2024. https://rshiny.ilo.org/dataexplorer22/?lang=en&segment=indicator&id=SDG_0131_SEX_SOC_RT_A&ref_area=AZE. Isiksal, A.Z. “The role of natural resources in financial expansion: evidence from Central Asia.” Financ Innov 9, 78 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-023-00482-6.

Kemp, Simon. “Digital Kazakhstan.” Datareportal. February 23, 2024. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-kazakhstan.

Najibullah, Farangis. “Real State Of Turkmen Medical Care A Far Cry From Official Images.” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. April 6, 2014. https://www.rferl.org/a/turkmenistan-health-careshortcomings/25322982.html.

Niyazova, Bilbil. “Türkmenistanyň oglanlary we gyzlary şeýle tapawutlymy? [Are boys and girls in Turkmenistan that different?].” July 24, 2021. https://public.flourish.studio/story/711888/.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Third periodic report submitted by Turkmenistan under articles 16 and 17 of the Covenant, due in 2023. Page 16. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=E%2FC. 12%2FTKM%2F3&Lang=en.

Our World in Data. Share of expenditure spent on food vs. total consumer expenditure, 2022. Accessed on November 20, 2024. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/food-expenditure-sharegdp?country=AZE~BLR~RUS~TUR~KAZ.

Peyrouse, Sebastien “The Health of the Nation—the Wealth of the Homeland! Turkmenistan’s Potemkin Healthcare System.” PONARS Eurasia. Policy Memos. February 13, 2019. https://www.ponarseurasia.org/the-health-of-the-nation-the-wealth-of-the-homeland-turkmenistans-potemkin-healthcare-system/.

Progres Foundation. How does the brain drain impact Turkmen society? January 8, 2021. https://progres.online/economy/how-does-the-brain-drain-impact-turkmen-society/.

Progres Foundation. Türkmenistanda işsizligiň derejesi: kime ynanmaly? [Unemployment rate in Turkmenistan: who to trust?]. April 13, 2021. https://progres.online/tk/ykdysadyyet/turkmenistanda-issizliginderejesi-kime-ynanmaly/.

Progres Foundation. Propiska düzgünini reformirlemelimi? [Should the propiska rule be reformed?]. August 17, https://progres.online/tk/jemgyyet/propiska-duzgunini-reformirlemelimi/.

Progres Foundation. The benefits of Internet in education: Why is it urgent to make it work without VPN in Turkmenistan? July 15, 2022. https://progres.online/internet-literacy/the-benefits-of-internet-ineducation-why-is-it-urgent-to-make-it-work-without-vpn-in-turkmenistan/. Progres Foundation. On being young in Turkmenistan. September 29, 2022. https://progres.online/society/on-being-young-in-turkmenistan/.

Progres Foundation. Digital Violence as a Mirror to Offline Realities: What does the public in Turkmenistan think about the status of women and girls? March 8, 2023. https://progres.online/reports/gender-equality/digital-violence-as-a-mirror-to-offline-realities/.

Progres Foundation. Palaw Index special report: How much palaw can you afford this Gurban Bayramy compared to previous years? July 10, 2023. https://progres.online/palaw-index/palaw-index-specialreport-how-much-palaw-can-you-afford-this-gurban-bayramy-compared-to-previous-years/.

Progres Foundation. Wages in Turkmenistan will increase again by 10%. Does it beat inflation? December 12, 2023. https://progres.online/economy/wages-in-turkmenistan-will-increase-again-by-10-does-itbeat-inflation/.

Progres Foundation. Civil Society Inside and Outside Turkmenistan: Searching for Meaningful Engagement in the Interest of the Turkmen Public. April 22, 2024. https://progres.online/reports/civil-society/civilsociety-inside-and-outside-turkmenistan-searching-for-meaningful-engagement-in-the-interest-ofthe-turkmen-public/.

Radio Azatlyk. В Дашогузе мобильные телефоны школьников проверяют на наличие порнографии, а у девочек и наличие девственности [In Dashoguz, mobile phones of schoolboys checked for pornography, and girls checked for virginity]. February 6, 2018. https://rus.azathabar.com/a/29021912.html.

Saglyk.org. Türkmenistanda Aýallaryň 50% Nähili Ýagdaýda [What is the situation of 50% of women in Turkmenistan?]. June 15, 2020. https://saglyk.org/makalalar/sagdyn-durmus/zenan-saglygy/1763-turkmenistanda-ayallaryn-50-nahili-yagdayda.html.

State Committee of Turkmenistan on Statistics (TurkmenState). Итоги сплошной переписи населения и жилищного фонда Туркменистана 2022 года [Results of the complete census of population and housing stock of Turkmenistan in 2022]. Accessed on November 21, 2024. https://www.stat.gov.tm. Statista. Average consumer price of studying at public higher education institutions per semester in Russia from 2016 to 2023. Accessed on December 8, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1237897/averagetuitionfeeatpublicuniversitiesrussia/#:~:text=One%20semester%20of%20studies%20at,26%20thousand%20Russian%20rubles%20lower.

Szarowská, Irena. “Importance of R&D expenditure for economic growth in selected CEE countries. E+M Ekonomie a Management.” December 2018. 21. 108-124. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329724399_Importance_of_RD_expenditure_for_economic_growth_in_selected_CEE_countries.

Turkmenportal. Starting from January 1, 2021, Turkmenistan will increase salaries, pensions, state benefits andscholarships. October 9, 2020. https://turkmenportal.com/en/blog/31110/starting-from-january-1-2021-turkmenistan-will-increase-salaries-pensions-state-benefits-and-scholarships.

Turkmenportal. State budget performance for 2020 approved in Turkmenistan. November 1, 2021. https://turkmenportal.com/en/blog/40981/state-budget-performance-for-2020-approved-inturkmenistan.

Turkmenportal. More than 25 thousand applicants were enrolled in universities and colleges of Turkmenistan in https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematic-composite-indices/gender-inequalityindex#/indicies/GII. August 30, 2022. https://turkmenportal.com/en/blog/51129/more-than-25-thousandapplicants-were-enrolled-in-universities-and-colleges-of-turkmenistan-in-2022.

United Nations (UN). Turkmenistan releases first-ever national survey on health and status of a woman in the family. August 26, 2022. https://turkmenistan.un.org/en/196699-turkmenistan-releases-first-evernational-survey-health-and-status-woman-family.

UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan on the progress of implementation of the Global Agenda for Sustainable Development 2023. July 6, 2023. https://turkmenistan.un.org/en/239049-voluntarynational-review-turkmenistan-progress-implementation-global-agenda-sustainable.

UN. 2037th Meeting, 87th Session, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW): Consideration of Turkmenistan. February 2, 2024. https://webtv.un.org/en/asset/k1g/k1gh3o5gro.

UN. Voluntary National Review of Turkmenistan. Ashgabat, Turkmen State Publishing Service 2019. Accessed on November 20, 2024. https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/documents/24723Voluntary_National_Review_of_Turkmenistan.pdf.